Photo of JP Mika by Riason Naidoo behind the painting entitled

Mwundu Na Pembe (Noir et blanc), 2019

JP Mika is holding his first solo exhibition outside the Democratic Republic of Congo. The show, called Bisengo, is on display at Magnin-A gallery in Paris until November 30. Mika emerged from the popular painting tradition of Kinshasa, where he was born in 1980. He is associated with the first generation of masters such as Chéri Samba, Moké, Chéri Chérin and Pierre Bodo, but has started to create his own unique style of paintings. Mika received attention and success when his works were included in the Beauté Congo 1926-2015 Congo Kitoko exhibition shown at the Fondation Cartier in Paris. A work from his oeuvre, Kiese na Kiese (2014), was chosen for the catalogue cover and advertising material, immediately making Mika the new poster boy of Congolese painting.

I met Mika recently at his studio at the Cité Internationale des Arts, where he is currently artist in resident.

When did it start for you in terms of art?

When I was 12 or 13 years old I started copying cinema posters for video distributors in Kinshasa — such as Jeando Mbenza, Katshofa Bobo and Suzuki — from whom cinema owners rented both the videos and the posters. Little by little I did bigger posters. It was through this work that I learnt to love colour, very strong colour. My first poster was about a Jackie Chan movie.

You attended the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Kinshasa. What was it like?

I went to the beaux-arts at the university for two years. Now there are black teachers — no more white teachers — but we are still in the Western tradition. The focus was on abstraction. I love detail and I put details everywhere. My professors there always told me not to pay too much attention to details; they wanted more abstraction. I followed my heart. I like things to be proper. When there is detail I am satisfied, more relaxed.

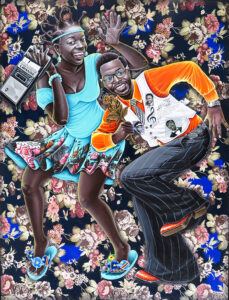

JP Mika. ‘Souvenir de la chanson de l’indépendance’, 2018. Acrylique, encre de Chine et paillettes sur tissu 186 x 143 cm. (© JP Mika/ ADAGP, Photo: Kleinefenn. Courtesy MAGNIN-A)

JP Mika. ‘Souvenir de la chanson de l’indépendance’, 2018. Acrylique, encre de Chine et paillettes sur tissu 186 x 143 cm. (© JP Mika/ ADAGP, Photo: Kleinefenn. Courtesy MAGNIN-A)

What is the difference between the classic and popular styles of Congolese painting?

For classic paintings, the public cannot understand these artworks. With popular paintings everyone can understand the painting. It is for our population. After the posters, I started with portraits and murals, especially portraits of musicians to attract people to the clubs. It was a sort of advertising. There were lots of figures in my paintings. It was about life in the streets, et cetera. I can now give the same message with one person in the painting. There is no need to paint the whole community to say the same thing.

You are known as the ‘God of Detail’. Tell me about this name.

When I started to create drawings, people gave me a nickname after Jean-Paul Gaultier, the French fashion designer. It was a quick name after someone famous, since Jean and Paul are my first names too. I didn’t talk much; others were talking a lot. I prefer my work to talk instead. So at the beaux-arts school the students called me the “God of Detail” because of my attention to detail.

You were an apprentice to the painter Chéri Chérin. Was this an important development?

In the art school they teach you how to be an artist. They teach you the value of being an artist, how to carry yourself, how to respond to questions, et cetera. I was with Chérin at the same time that I was at the art school. Apprenticeship is good. Before that I can say that I was decorating. A painting on canvas, a tableau is something completely different. When I was first with Chérin, he said it was good to know colours, et cetera, but I didn’t know how to have ideas, concepts. The first composition I did was Beauté Africaine (2007), which was when I started to learn how to compose an artwork.

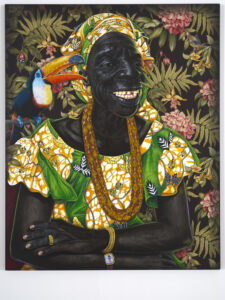

JP Mika. ‘Sango Malamu (La bonne nouvelle)’, 2019. Acrylique, encre de chine et paillettes sur tissu. 150 x 120 cm. (© JP Mika/ ADAGP, Photo: Kleinefenn. Courtesy MAGNIN-A)

JP Mika. ‘Sango Malamu (La bonne nouvelle)’, 2019. Acrylique, encre de chine et paillettes sur tissu. 150 x 120 cm. (© JP Mika/ ADAGP, Photo: Kleinefenn. Courtesy MAGNIN-A)

Can you talk about the influence of Chérin and Chéri Samba on your work?

I was influenced a lot by Chérin. He showed me a lot about paintings — he showed me the way. Once I painted some small decorative pendants for Chérin. Chéri Samba saw this and asked Chérin who painted it because there was so much detail there. Chérin replied: “It was not me, it was my student JP Mika.” That’s how I met Samba. It was at the end of 2008. Now he invites me whenever he has some shows or events. From Chérin I learnt about composition; from Samba I learnt about the finesse and details.

Are your works inspired by images in popular culture?

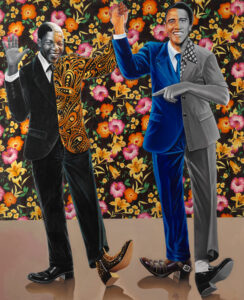

Chérin and Samba work with politics. I wanted to work with joy and humour. You know the painting with Nelson Mandela and Barack Obama entitled Mandela dignité pour l’Afrique (2014). I wanted to make something different. It’s my style — the style of JP Mika. I’m considered an artist. At home, when you are an artist, it means having many girlfriends. I wanted to show a different way to be an artist. I wanted to show another way, to be an example — a role model.

I have read that some of the common themes in Congolese art are Mami Wata, the colonial era, et cetera?

They are right. Even our generation does themes of Mami Wata. We followed the older generation. I also did Mami Wata but it was different to Samba. Nowadays many artists are working on the themes of sape (the Kinshasa dandy tradition) and also of kinoiserie (the people of Kinshasa). Everyone is doing sape, but each in their own manner.

JP Mika. ‘Jackie Chan “La Hyène Intrépide”‘, 1993 – 2019. Videothèque Jeadot-Mbenza Production, Signé JP.EL Gauthier, Savane, Silence du Gd Chef. Huile. sur papier 88 x 76 cm. (© JP Mika / ADAGP, Photo : Kleinefenn. Courtesy MAGNIN-A)

JP Mika. ‘Jackie Chan “La Hyène Intrépide”‘, 1993 – 2019. Videothèque Jeadot-Mbenza Production, Signé JP.EL Gauthier, Savane, Silence du Gd Chef. Huile. sur papier 88 x 76 cm. (© JP Mika / ADAGP, Photo : Kleinefenn. Courtesy MAGNIN-A)

Some of your paintings show characters standing in a photo studio inspired by images we have seen in Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta’s photos of the 1960s and 1970s in Mali. What inspired you?

I did these kinds of paintings before the Beauté Congo exhibition in Paris. Now I don’t do that so much. Artists started copying my style, so I changed my style. I paint about the past and about the present with this style. In Sidibé photos it is movement that inspires me. Even if there is no movement in the paintings, I add this in my way. I created my own studio images. There is joy and hope in these paintings too.

Could you talk about your technique of using a found textile as a canvas? What inspired this?

In 2006 Chérin told us that the French curator and gallerist André Magnin was going to be visiting Kinshasa and we must prepare some work for him to view. Magnin said that I was making work too close to Chérin. When I heard that it made me sick. He told others too that they were copying other better-known artists from Kinshasa.

When I went to Spain in 2008 on residency with Chéri Chérin, it was my first trip outside the country. When I returned I made a painting of Obama and I sent an image to Magnin, who said he’d buy the painting to encourage me. He said I must continue like that. I prayed to God to inspire me to create work different to the others. From then, I wanted to make something unique.

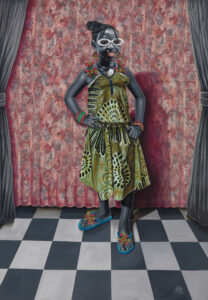

I first started with this style of the patterned fabric in the painting La Nostalgie (2014). I sent an image to Magnin and he said that now I was starting to make something different. It is in the Beauté Congo catalogue from the exhibition at Fondation Cartier.

I love to use material with a floral print. At home, and also in the world, there’s a lot of sadness. I like to show joy, hope and happiness. I like to have flowers in my paintings: it is a symbol of joy. Everything at my place is decorated with flowers: chairs, suitcases, clothes, baskets, everything. It’s part of my identity. I want to be one with my work — a marriage, a tableau vivant. There are a lot of emotions in the paintings and in me.

JP Mika. ‘Mandela dignité pour l’Afrique’, 2014. Huile et acrylique sur toile 170 x 160 cm. (© JP Mika / ADAGP, Photo : Kleinefenn Courtesy MAGNIN-A)

JP Mika. ‘Mandela dignité pour l’Afrique’, 2014. Huile et acrylique sur toile 170 x 160 cm. (© JP Mika / ADAGP, Photo : Kleinefenn Courtesy MAGNIN-A)

There is a tradition of representing independence leader Patrice Lumumba in Congolese popular painting. You have also followed this. What does Lumumba represent for you?

Lumumba is an icon for us. He opened Congolese eyes with regard to politics. During independence, he was not afraid to voice his opinion. One painting I made called Histoire Commune (2017) depicts Lumumba, Kwame Nkrumah and Nelson Mandela. The paintings also reflect historic moments. There is one painting I did called Declaration of Independence (2000), a small painting of Lumumba, which reflects on when the Congolese took to the streets for independence. The speeches of Lumumba woke up the people.

There is also the painting of Nelson Mandela and Barack Obama called Mandela dignité pour l’Afrique (2014) that you referred to earlier.

Mandela symbolises the dignity of Africans. He was in power and showed the way, and then he stepped down and left it to others to carry on. This you do not find easily. It is very, very difficult to leave power like that, as he did. You don’t see that in Africa. Normally there is war, bloodshed and a lot of struggle.

Are people the source of inspiration in your paintings? Do you paint for the people?

I make art for the world. There is a lot of talent around at the Cité Internationale des Arts and on the streets of Paris. My talent and inspiration are divinely inspired but that’s not enough to succeed. It’s not entirely of my own making.

JP Mika. ‘La nostalgie’, 2014. Huile et acrylique sur toile 169 x 126 cm. (© JP Mika / ADAGP, Photo : Kleinefenn. Courtesy MAGNIN-A)

JP Mika. ‘La nostalgie’, 2014. Huile et acrylique sur toile 169 x 126 cm. (© JP Mika / ADAGP, Photo : Kleinefenn. Courtesy MAGNIN-A)

Have people in Kinshasa commissioned you to paint their portraits?

They are fans. They don’t have much money. It gave me pleasure because it was people who appreciated what painters do. I often did a painting for a marriage. It is the best present you can give. I have done a few portraits. Sometimes when attended a wedding, I’m well dressed and I get a lot of attention but I don’t feel so good to take attention away from the couple, so I don’t stay long. Before I did it for nothing. Now I ask for something in exchange. They would give me a photo or I take a photo and I would work from that. I take a lot of pride to do my best because I know it’s my work, my reputation. Even in France people have commissioned me to do a portrait for their wedding.

What can people see in your latest exhibition?

I use the floral print a lot in my paintings but there are different techniques. There are some with the textile where the colours of the background and skin are the same. In others I use black for skin colour, others still with natural skin colour, et cetera. There are also some posters from when I was 13 years old — the first posters I made. I recreated these posters in 2019 while in residence here at Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris. I found the film posters on the internet and I created these again because we were using the original posters as reference when we started in Kinshasa, copying from the video covers.