There is strong bipartisan and beneficiary support for making improvements to Agoa.

In his 2020 budget speech, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni said South Africa is opening its market to trade with the rest of Africa to promote regional integration and contribute to economic growth.

Mboweni said this will be done through the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which South Africa signed up to last year.

The AfCFTA is a trade agreement among African countries that aims to create a single continental market through which goods and services would freely move. This deal is forecast to generate a gross domestic product (GDP) of $2.5-trillion and would encompass a market of 1.27-billion people.

The free movement of goods will be achieved by promoting intra-Africa trade and lowering tariffs.

The AfCFTA will be the world’s largest free-trade area by number of countries since the formation of the World Trade Organisation.

At the Black Business summit on Wednesday, AfCFTA secretary general Wamkele Mene, said the negotiators would have completed everything by the July deadline for the trade area to come into force.

He said the negotiators are hard at work in Addis Ababa, trying to conclude the outstanding trade negotiations. He added that the rules of the origin of goods were 90% completed, with only automobiles, textile and clothing and sugar needing still to be negotiated. “I am confident that we are going to conclude these outstanding areas,” he said. “We are accustomed to working under very severe time constraints.”

The decision to start working towards the trade agreement was adopted by the African Union in January 2012, with plans for it to be initially established by 2017.

“This [the African Continental free trade area] is an incredibly ambitious project. You are trying to integrate 55 members of the African Union, and they are very diverse in terms of levels of economic development,” said Trudi Hartzenberg, executive director at Trade Law Centre (Tralac), an organisation that develops technical expertise and capacity in trade governance across Africa.

Hartzenberg said what makes the trade area so difficult to negotiate is the fact that the continent is home to many of the world’s least-developed countries, with many of them landlocked and lacking diverse economies.

Despite this, growth in many countries is outpacing that of South Africa, which grew by only 0.2% last year. Nigeria’s GDP, by comparison, was forecast to grow 2.3%, and Rwanda’s by 8.7%.

Although South Africa is part of other regional trading blocs, such as the Southern African Development Community, Professor Mzukisi Qobo from the University of the Witwatersrand School of Governance said the AfCFTA will have a greater effect on continental trade because of its scale.

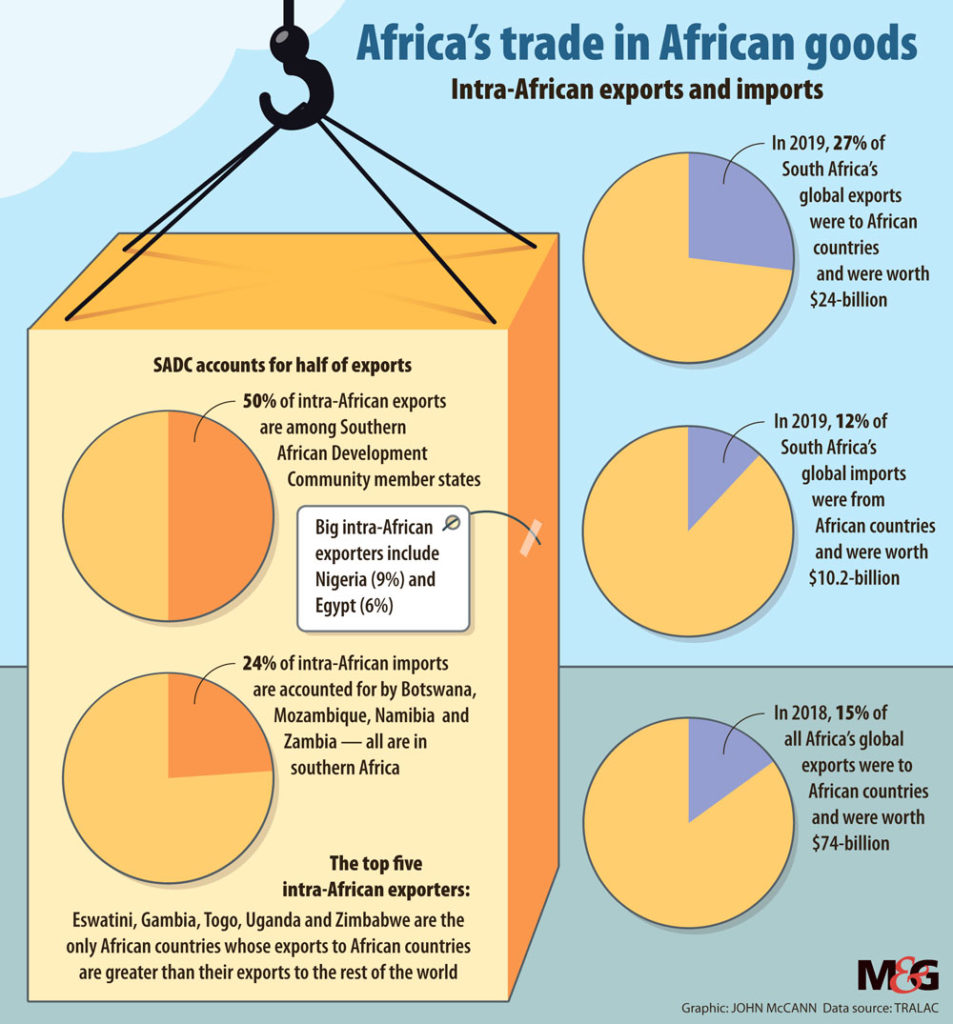

According to Tralac figures, South Africa is the biggest intra-Africa exporter. It accounts for 34% of the intra-continental exports and 20% of intra-African imported goods coming from the continent. With the free trade area, Qobo said these numbers will increase and positively affect the country’s growth.

At the signing of the agreement in 2018, Rwandan President Paul Kagame, who was then the chairperson of the AU, said in his keynote address that “less than 20% of Africa’s trade is internal” and “in the world’s richest regional trading blocs, the level of internal trade is three or four times higher”.

In 2018, intra-African exports were valued at $74-billion. Between 2017 and 2018 intra-Africa exports increased by only 1%, although Africa’s exports to the rest of the world increased by 22%.

Kagame said the agreement does not mean Africa will do less business with the rest of the world. “On the contrary, as we trade more among ourselves, African firms will become bigger, more specialised, and more competitive internationally.”

Dr Sithembile Mbete, a senior lecturer at the University of Pretoria, said African countries trade less with each other compared to European and Asian countries.

According to the United Nations’ Economic Development in Africa Report from 2019, intra-African exports were 16.6% of total exports in 2017, compared with 68.1% in Europe, 59.4% in Asia, 55% in the Americas and 7% in Oceania.

Mbete said the median age in Africa is 19.7 years, meaning half of the population is younger than 20 years old. She added that, by 2100, 50% of all young people will be living in Africa. “If African countries want to develop economically, they need to trade with each other because that is where the people will be. Every other region in the world is getting old,” she said. “The rest of the world is gearing up to harness and exploit that market [Africa] and we also need to [take] control of that process so it’s not a reverse colonisation.”

Trading under the AfCFTA is scheduled to commence on July 1. But Hertzenberg said there is still more work to be done before then. “In each of the categories there are so many technical issues that need to be negotiated,” she said.

These range from determining what the economic nationality of a product actually is (if you make cars in South Africa but the parts are sourced from somewhere else, are they South African?) to how customs and border agencies deal with goods arriving and crossing borders.

One of the key steps is for countries to lower import duties, so goods coming from one African state to another aren’t subject to high taxes (which makes it more difficult for countries to compete with other exporters). This is why, for example, goods produced in China and sold in Kenya can be cheaper than goods from neighbouring Uganda, depending on each country’s trade deals.

Hertzenberg cautioned against expecting too much from increased trade, warning that the trade agreement cannot solve all of Africa’s problems. “It can deliver certain things, but it’s not a solution to every problem we face on the African continent,” she said. Hartzenberg noted problems such as lack of infrastructure and the skills deficit that the trade agreement cannot deliver on .

Qobo said that, nationally, countries first need to be aware of the work they need to do internally to reap the benefits of the agreement. He said this is not the first venture that the AU is embarking on to bolster regional trade but that previously its efforts lost momentum. This is because “governments tend to care about what happens in their own countries”.

He added that: “The political calendar of heads of government is very short and integration is a long-term project. So they worry about what will get them elected in their own countries.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Tshegofatso Mathe is an Adamela Trust business reporter at the Mail & Guardian