Moves: Babusi Nyoni created the Vosho app for fun, but found that it could be used to diagnose Parkinson’s disease that, among other things, affects movement. (Photos: Courtesy of Babusi Nyoni & Lusanda Worsley)

In Africa, for every region, there’s a dance. Azonto. Rimbaxpaxpax. Alkayida. Skelewu. Bolo. Coupé-Décalé. Shoki. Some are more involved than others. The most recent to separate the kinetically intelligent from the choreographically challenged is the vosho. Merging strength, joint health, rhythm and stamina, the vosho reached prominence in late 2017 and its many iterations have had the staying power to confuse and delight us in equal measure.

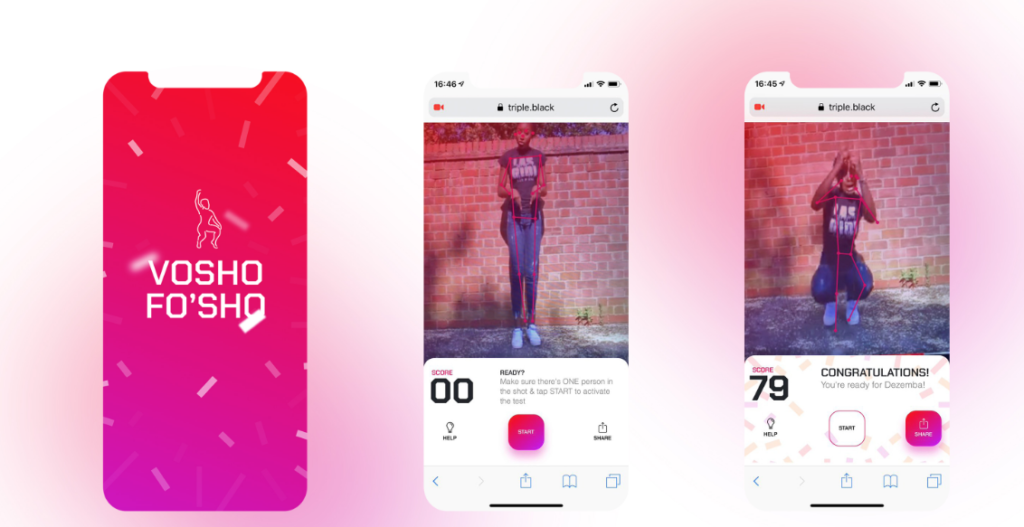

By now you ought to know the difference between a quality vosho and a potentially ligament-threatening one. According to the Vosho Fo’sho app: a good vosho is quantifiable.

Vosho Fo’sho App screens.

Vosho Fo’sho App screens.

Its creator, a self-taught Zimbabwean design strategist and innovator, says the speed of your descent relative to your body’s weight and how quickly you can come up, unscathed, is key. All while doing so rhythmically.

Babusi Nyoni created the app as a gag. His vosho is finicky. Those who can’t do, apparently make apps. The app which he released just in time for December 2018 has now found a way to be effective outside of entertainment.

We move: Babusi Nyoni created the Vosho app for fun, but found that it could be used to diagnose Parkinson’s disease that, among other things, affects movement. (Photos: Courtesy of Babusi Nyoni & Lusanda Worsley)

One of those experiments was the vosho app. Nyoni says he wanted to see what else he could do with the data collected by the app. Dance is a great communicator and rehabilitation tool, but what about using it as a diagnostic tool? The formula to define a good vosho boils down to movement assessment over time. How low a dancer can go and how quickly they can come back up without help. Did their posture change? Was their gait altered by the dance. There are a variety of conditions and diseases that degenerate motor skills over time.

One condition that relies on movement assessment over time for prognosis is Parkinson’s disease. The neurological disorder is progressive and one of the first symptoms exhibited is problems with movement.

Needing a research partner to test his hypothesis, on the advice of his research intern Sean Ndlovu, Nyoni solicited the help of head nurse Sukoluhle Hove of the Ekuphumuleni Geriatric Nursing Home in his hometown of Bulawayo in Zimbabwe. Together they developed a research plan and gathered insights that went on to inform the usability of an app in assessing subjects’ posture, gait and tremors.

Photos: Courtesy of Babusi Nyoni & Lusanda Worsley

The process Nyoni describes as one of ongoing informed consent and collaboration with the home’s residents and Hove to build an experience that worked around residents’ physical needs.

Head Nurse Sukoluhle Hove

Head Nurse Sukoluhle HoveDuring testing, Nyoni witnessed a resident stumble. That near-fall and the physical demands of testing was not something Nyoni and his team would have thought of, he says. A direct outcome of this phase was the merging of two separate gait and posture tests into one to ensure test subjects’ comfort and to limit the required movements in each assessment.

The resultant app, Patana AI (named after his mother’s home village in rural Matebeleland South) is now available on both Android and iOS operating systems.

Using real-time pose-estimation, his app has a second life — identifying the symptoms of the pervasive movement-altering condition.

Using TensorFlow, an open-source machine learning library developed by Google Brain — a deep learning artificial intelligence research team at the search titan — the app was optimised to work on the most rudimentary of smartphones. All a user had to do was point and shoot even with a low-end smartphone camera.

For Nyoni this is one example of many tech failures out there. He says there are technologies out there that don’t take into account who they are serving and their unique community-specific challenges, like intermittent electricity supply.

He says there is an audience for new technologies on the African continent. But for it to make any tangible, lasting and positive differences for the people using it, it must be made in context.

“Tech has to serve a purpose. It has to be contextual to where it’s made. When we started Tripleblack Agency we wanted to make impactful things using [new] technology, but a lot of our clients didn’t understand the tech. So instead, we took a year to experiment with machine-learning and artificial intelligence on our own terms,” he says

The core value of the digital agency — Tripleblack — which he co-founded — is to make “super interesting tech things that hinge on the African experience”. A lot of the technology that finds its way to our shores is “hand-me-down” in that it is developed elsewhere with Africa as an afterthought, not as the main consumer.

Take facial recognition software, for example.

Computer vision algorithms have never been so good at distinguishing human faces. But there is a caveat: for them to work, those faces have to be pale, or Caucasian. Facial recognition is becoming more common-place in consumer products and law enforcement, backed by powerful machine-learning technology. But technology is not race-neutral. A test of readily-available commercial facial-analysis services often produce skewed results. The systems scrutinising our features often show significantly less accurate results for people with black skin. Other criticisms levelled include “white-washing” the skin tones and facial features of users with darker skin tones.

A year after its creation, the prototype for the app has been showcased at the TensorFlow World Conference where Nyoni had been invited to speak about its uses beyond rating dance moves and possibly, in conjunction with guidance from healthcare practitioners, diagnosing Parkinson’s disease. The Silicon Valley trip was part of a year-long speaking tour for Nyoni, which saw him visiting France, Switzerland, Kenya and the Fak’ugesi African Digital Innovation Festival in Johannesburg at the end of 2019.

He has since quit his day job to fully immerse himself in Patana and another platform, Sila, which connects Africans to volunteer healthcare professionals through the use of popular chat platforms.

Despite attention from the West, Nyoni says this is an African solution for an African problem. Patana’s a collaborative effort between Ndlovu, Nyoni and Cape Town illustrator, Russell Abrahams. “We appreciate the work the TensorFlow.js team has put into making their machine learning framework work on low-end mobile devices to power apps such as this.” Nyoni laughingly adds: “It is a deliberately African solution to a global problem.”