‘Humiliating questioning’: A resident of Jeppestown workers’ hostel in Johannesburg is detained by a policeman during Operation Fiela in 2017. (Marco Longari/AFP/ Getty Images)

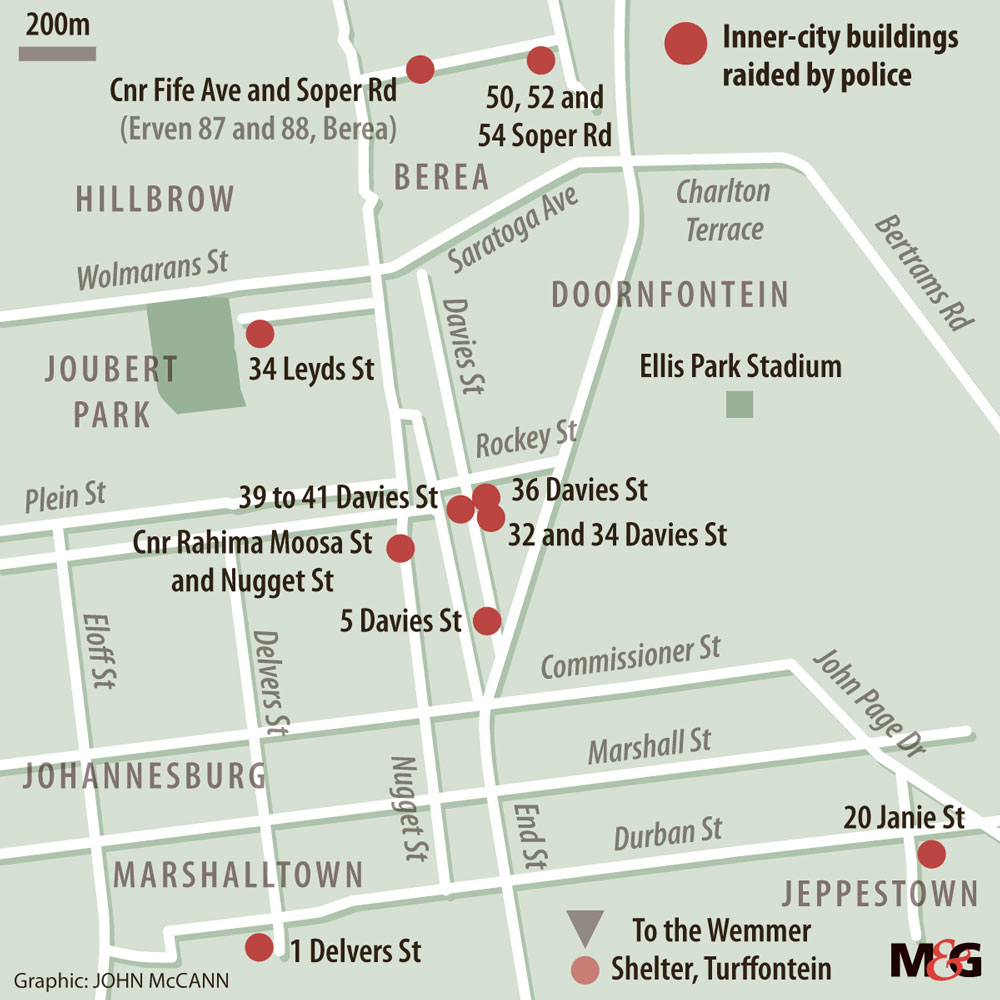

Between June 2017 and May 2018, the police conducted a series of 20 raids on 11 buildings in the Johannesburg inner-city. The raids revived the controversial Operation Fiela, which means “sweep” in Sesotho, and were conducted on buildings deemed to be hide-outs for criminals.

With the help of the Johannesburg metropolitan police department and officials from home affairs, police forced residents of the buildings out on to the streets, where they were searched, fingerprinted and commanded to produce their IDs.

Anyone who could not produce documents proving they were in South Africa legally was detained. Those who were not arrested returned to find their homes and possessions in disarray.

These were the buildings that were raided by the police. (Graphic: John McCann)

These were the buildings that were raided by the police. (Graphic: John McCann)

The raids were conducted in terms of section 13(7) of the South African Police Service Act, which empowers the police to search any person or premises without a warrant to “restore public order or ensure the safety of the public”.

On Monday, the more than 2 000 occupants of the buildings, represented by the Socio-Economic Rights Institute (Seri), asked the Johannesburg high court to declare the section unconstitutional and invalid.

They took on the South African Police Service (SAPS), as well as the department of home affairs, the City of Johannesburg, and its erstwhile mayor Herman Mashaba — arguing that these entities waged a co-ordinated attack on their constitutional right to privacy.

The court battle was heard by a full Bench of three judges, including the division’s most senior judge, Judge President Dunstan Mlambo, as well as Judge Fayeeza Kathree-Setiloane and Judge Pieter Meyer.

In an affidavit to the court, Seri executive director Nomzamo Zondo said the raids constituted an “unlawful and far-reaching invasion of the applicants’ dignity”.

“The applicants’ homes were invaded and the sanctity and tranquillity of those homes was destroyed. The questioning they were subjected to was obviously humiliating,” the affidavit reads.

“The fact that many of the raids took place while the applicants were sleeping, and that the applicants were often dragged out of their homes in their underwear or nightclothes was likewise humiliating.”

The residents argued that section 13(7) of the Act infringes on the right to privacy. But the SAPS maintained that the section is vital to its efforts to restore public order amid rising crime rates.

Counsel for the residents, Stuart Wilson, pointed out that “there is not a single case in which the Constitutional Court has held that warrantless searches are constitutionally permissible”.

He pointed to five decisions by the apex court that found that provisions that authorise warrantless searches of private homes are seldom justifiable.

But Mlambo pointed out that all the decisions referred to by Wilson “have nothing to do with public order”. Meyer added that all the cases referred to are “fact specific, whereas this provision deals with this situation where law and order should be restored. Or, within a specified area, people’s safety is at risk.”

“My submission in response is that that may be true, but one applies general principles to specific facts,” Wilson retorted.

“And you’re bound — I don’t need to tell you this — but you’re bound by the decisions by the Constitutional court on warrantless searches … And our first submission is that the Constitutional Court has never permitted warrantless searches.”

Wilson added that the top court “has never allowed legislation to stand that authorises warrantless searches of whatever nature”.

He further argued that section 13(7) offers “extremely” broad discretionary powers to police officers “to invade constitutional rights”.

In his heads of argument, Wilson notes that under section 13(7) of the Constitution: “Anyone may be searched, at any time, so long as a police officer thinks this is ‘reasonably necessary to achieve’ whatever object the police commissioner specifies in the authorisation.”

On Monday, he contended that “legislation that grants discretions to, especially junior, police officers and other officials can’t be too blank, can’t be too-open ended. And here we say it is blank and it is open-ended.”

Wilson said it was not enough for the provincial police commissioner — who at the time was Deliwe de Lange — to authorise the section 13(7) search by simply saying “crime”.

“The provincial commissioner who issued the authorisations had to be satisfied that the situation was so grave as to justify widespread warrantless searches,” he said.

“They had to be satisfied that the level of crime had reached proportions that threatened public order and safety was linked to the applicants … They don’t even begin to establish that.”

Mlambo intervened: “Is it correct … that predominantly the residential areas are hijacked buildings?”

But Wilson said his clients take “strenuous issue” with the phrase “hijacked buildings”.

“We don’t know what it means. What we accept is that our clients live in buildings where they don’t have consent of the person in charge to live there … If that is what they mean by hijacked buildings, then the phrase … is a deeply inappropriate way of referring to people in the applicants’ situation.

“The applicants are desperately poor people who would be rendered homeless if they didn’t live in the buildings they currently live in. They haven’t hijacked anything.”

He added that the residents “deserve a measure of respect and dignity that is taken away from them when they are willy-nilly referred to as hijackers”.

“This pejorative term enables junior police officers to exercise their broad discretions in a way that are based on social prejudices and not on legal principles.”

But Moses Mphaga SC, on behalf of the SAPS, contended: “As we argue about the rights of the applicants, we cannot ignore the rights of those affected by violent crime.”

He argued that section 13(7) is not inconsistent with the constitutional right to privacy.

Mphaga said police officers must exercise their powers under the section in a way that does not intrude on the constitutional rights of the people they are searching.

Individual policemen may have acted in a way that was inconsistent with the Constitution when they conducted the raids, he said.

“But then they from a point of the commissioner, he had only indicated to them: ‘Please, when you go and implement this authorisation, you must be conscious of the fundamental rights of the people.’ So if the policemen, when they arrived at the scene, and they implemented contrary to what the commissioner says, it cannot make the authorisation itself unconstitutional.”

Mphaga later added: “The fact that we have so many unlawful arrest cases in a country does not necessarily make the provision that authorises those arrests unconstitutional.”

When pushed by Mlambo about when it is justifiable to impose on privacy rights, Mphaga said, “There is a justification for the police to have these extraordinary powers … to ensure that they normalise the crime levels of an area.”

But Kathree-Setiloane pointed out that the applications for the section 13(7) authorisations each used the same crime statistics, despite them being made months apart. “That means all your searches were completely useless.”

Mphaga responded: “But the statistics are there and they are saying that this is unacceptable.”

In response to Mphaga’s argument, Wilson said that it is “not appropriate in these circumstances to say that the section is okay because we can trust the police to keep the Constitution in their hearts”.

Quoting the Constitutional Court, he added: “One must be careful to ensure that the alarming level of crime is not used to justify extensive and inappropriate invasions of individual rights.”

Judgment was reserved.