Defiant dreams: Pictures are used without captions in Saidiya Hartman’s book.

In her latest book, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (2019), Saidiya Hartman resurrects the lives of those who are defaced and dispossessed by history. These are the lives of nameless and ordinary Black women that history, by default, registers as minor figures or forgets altogether.

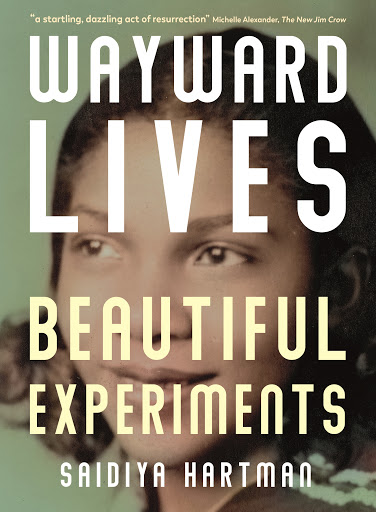

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval by Saidiya Hartman (WW Norton & Company)

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval by Saidiya Hartman (WW Norton & Company)

The book unfolds after the legal end of racial enslavement, at the dawn of 20th century in the United States. This is the period between the 1890 and 1935; a time that marks the beginning of what Hartman describes as the anarchy of young Black women who experiment with freedom, in the wake of “new forms of servitude awaiting them”.

Wayward Lives is Hartman’s third book following her historiographical memoir, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Route (2006), and her debut, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (1997).

It was during the spring of 2019, while in Durban, planning the upcoming Black Studies Mobile Academy with Tina Campt and Mabel Wilson (her colleagues in the Sojourner Project), that Hartman received the news that she had been honoured with the MacArthur genius grant. The bestowal of this award comes with little surprise, considering the contribution that Hartman’s work has layered into our ongoing understanding of the “afterlife of racial slavery”. All three of her books share this common thread.

“Critical fabulation” and “Black fungibility” are a few notable concepts from Hartman’s inventory of travelling ideas that have a home in all areas of Black study. In contrast to her previous work, in Wayward Lives, Hartman focuses specifically on the experiences of young Black women. She illuminates the perspectives of Black women through a vividly cinematic narrative from where we are positioned to view the world through their eyes. This review focuses on some of the ways that Hartman uses visuality and selected imagery to drive the narrative and plot in the book.

Wayward Lives is populated by a fleeting cast of Black women whose lives are scripted into servility and confinement. Inside this treacherous climate, they “try to make a way out of no way”. Hartman’s protagonists experiment with defying gravity in a climate that is encoded by the logic of antiblackness that pulls Black women in a downward vortex.

At the brink of a new century, connected by the “desire, pain and the promise” of refusing to be at the bottom, Hartman’s cast of women heeds the restless chorus of movement, “to get out, to go anywhere but here, to go somewhere better than this”.

After racial enslavement, this movement could be only upwards and away from the rural southern states, where racism was still raw and wolfish. For Black women on the move, the north was a better prospect, despite the fact that it was also riddled with a tricky type of white liberal racism that was pervasive in the city — and was a task to outfox.

Wayward Lives is organised as three books in one. The Terrible Beauty of the Slum ushers in the first book, in which Hartman narrates the urban landscape from where her stories unfold. The focus is on the promise and precarity of transient spaces and liminal zones such as the streets, passages, stairwells, doorways and the tenement alleys of Philadelphia and Harlem.

From here, Hartman takes us inside rented rooms, a workhouse, theatres, an attic studio, kitchenettes and a reformatory for women. These are some of the spaces that hint at the type of labour that her characters perform. After the plantation, the ghetto becomes the new enclosure from where history’s unlikely protagonists craft other ways to live.

What is striking is how Hartman writes in a visual prose that heightens our attention to the role of the camera and the hypersurveillance that stalks Black social life. In narrating the “terrible beauty” of Black modern life, she reveals the vampiric ways that Black social life is consumed and enjoyed by outsiders.

This is apparent in the following lines: “Outsiders call the streets and alleys that comprise her world the slum. For her, it is just a place where she stays …

“The voyeurs on their slumming expeditions feed on the lifeblood of the ghetto, long for it and loathe it. The social scientists and reformers are no better with their cameras and their surveys, staring intently at all the strange specimens…

“The sons and daughters of the rich come in search of meaning, vitality and pleasure”.

This predatory gaze becomes more apparent in the small photograph of Girl #2. The picture was taken 1882, 70-odd years after Sarah Baartman’s brutal disrobing across the Atlantic ocean. Awkwardly reclining on a sofa, in the nude, in the presence of an adult male artist photographer, the girl can’t be more than 10 years old. We are looking at a picture of a Black girl child trapped in an attic studio; vulnerable to bad touch, she cannot defend herself. For Hartman, the picture of the girl becomes a portal from where she reflects on all “the terrible things that could be done to a Black girl without a crime having occurred”.

For us, both as readers and spectators, this is an image inviting us to participate in violation. In light of this, Hartman urgently questions, “Was it possible to annotate the image, to make my words into a shield that might protect her, a barricade to deflect the gaze and cloak what had been exposed?”

In an act of Black feminist care, Hartman belatedly intervenes in this scene by placing a barrier of text over the faded picture of the anonymous girl’s exposed body. A wall of sentences hovers in the foreground, obviating what would be an open gaze. In doing this, she inserts a dignity that was bereft from the entire act of conceiving the original photograph. Through this act she evokes Carrie Mae Weems’s dignifying methods in her tinted photographic series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried.

In congruence with Tina Campt’s (2017) alternate take in Listening to Images, Hartman is attentive to the muted frequencies of the photograph. In Wayward Lives, Hartman critically fabulates with images in ways that allow her to affirm their low-key “gestures of refusal”. Theorised by Hartman, critical fabulation is a mode of storytelling that involves subjunctive and critical speculation on the gaps and silences of official archival records relating to the transatlantic slavetrade.

The author critically fabulates with images in ways that allow her to affirm their low-key ‘gestures of refusal‘. (Catherine T MacArthur Foundation)

The author critically fabulates with images in ways that allow her to affirm their low-key ‘gestures of refusal‘. (Catherine T MacArthur Foundation)

This is a method that the author uses in her work as a way to open up new narratives within the conditions of absence and erasure, which generally haunt the modern Black archive. When read against the grain, in opposition to its original design, the photograph of Girl #2 starts to straddle a simultaneous existence, not just as a “still life”, but also as “a runaway image that conveys the riot inside” of it. Through this refracting gaze, the photograph of Girl #2 stands in for the stories of the Black girls who will appear after her in the latter chapters of the book. These are characters such as Mattie Nelson, Eva Perkins and Mabel Hampton, to name a few; dark-skinned girls who, at the cusp of womanhood, yearn for freedom.

They defiantly dream other lives into existence, ones in which their horizon isn’t limited to “a maids uniform” or “a white woman’s dirty house” or “mothering other people’s children”. In this other life, they “would not be required to take all the shit that no one else would accept and pretend to be grateful”. In her defiance of the enclosure, Eva Perkins sets off a sonic riot that echoes the grammar of the Black music tradition. Mabel Hampton’s escape from domestic servitude is on the stage, where she can sing in opera and dance in ways that elude capture.

Wayward Lives is a love letter written to those who defiantly dance with death. Written from “inside the circle”, where the voice of the narrator is often indistinguishable from voices of the characters, Hartman’s book is an act of surrendering to the chorus of our ancestors.

Zamansele is a lecturer in cultural studies at the English department at the University of Johannesburg