This time seems different: A Black Lives Matter mural on a street in Brooklyn, New York, during protests against racism after the killing of George Floyd. (Photo: AFP)

The South African economy, a quarter of a century after democratic elections, is not inclusive. This lack of capital, and of investment, ownership and representation at board level, reveals a country that has not transformed.

In the United States, after police killed George Floyd on May 26, protests started again under the Black Lives Matter movement. It is not the first time. But this time seems different, with the New York Times reporting that it might be the largest movement in the history of that country.

Part of the practical change effected by the movement — not just in the US, but around the world, including South Africa — has been a call to support black business, both as customers and by creating the structures that allow black businesses to compete equally.

But let’s start with the foundation — why is there a call to support black businesses?

Keitumetse Diseko, head of marketing at the BrownSense Group, says racism is a structural phenomenon rooted in the exploitation of particular groups that don’t possess political and economic power.

“The two are inextricably linked, so you cannot fight racism without fighting to empower black people economically. In the US, slavery and legalised racism ended decades ago; however, institutionalised racism has never been addressed, and this is how they arrive at their current situation,” Diseko says.

BrownSense Market is a platform that gives black businesses access to diverse markets by using a Facebook group or the group’s e-commerce platform. The platform was founded in 2016 as a response to the normalised racism faced by black people in all sectors of South Africa. For example, people would not shop at a black-owned store, or would not support black businesses in other ways.

“It [the market] is an instrument for the black community to exercise agency in building and growing our community,” Diseko says.

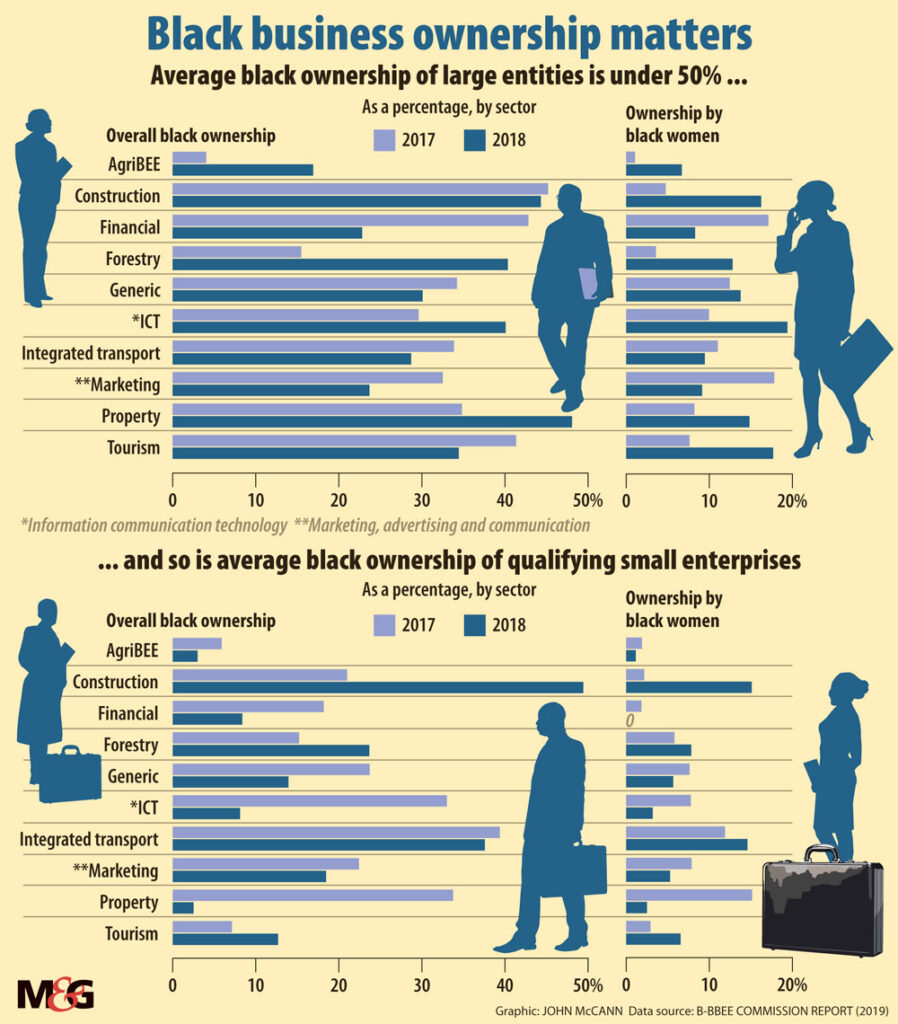

This reality is regularly borne out in economic data, such as a 2015 statement from the JSE saying that black South Africans held only 3% of the direct investment in the exchange’s Top 100 listed companies. That grows to just 23% when you include direct and indirect holdings.

Diseko says South Africa has a legacy of apartheid and colonisation that still hangs over its people — even in the present day — which profits and reinforces white control and wealth.

She says to dismantle this system all South Africans should include black people in the mainstream economy by consciously deciding where they spend their money — from supply-chain spending to education and training. She says a crucial element is black people having fair access to finance and funding processes that do not discriminate against them.

Diseko says there is assistance from the government, but many businesses cannot access it because of a lack of access to information, as well as red tape and corruption.

Investing in black companies is not only the right thing to do, says Diseko, it also makes economic sense. This kind of focused spending and investment will create stronger communities and a more robust and competitive economy, build local economies and empower small businesses to employ more people. This will eventually lead to the alleviation of poverty in the black communities.

Kganki Matabane, chief executive of the Black Business Council, says there has not been enough meaningful assistance for black businesses.

Kganki Matabane, the chief executive of the Black Business Council, says there has not been enough meaningful assistance for black business. (Photo: Sfiso Sibanyoni)

Kganki Matabane, the chief executive of the Black Business Council, says there has not been enough meaningful assistance for black business. (Photo: Sfiso Sibanyoni)“It is an open secret all over the world that businesses and governments have been paying lip service to supporting black women and youth-owned businesses, including businesses owned by people with disabilities. As such, it is not surprising that the movement [Black Lives Matter] caught fire so quickly globally, as the ground has been fertile. I think people have had enough and are tired of knees being put on their necks”.

Matabane says most people are reluctant to support black business by “deed” — with their money. Instead, people can be influenced by the notion that products created or owned by white business people are of a better quality than products from black businesses.

Matabane lambasted the R200-billion coronavirus loan scheme, which is facilitated by banks to aid small businesses. The requirement is that businesses should be in good standing with their bank. He says black businesses face cash-flow problems, including being paid late or not at all for work they have completed.

“If you get paid late or not paid at all, you can’t be in good standing with the banks. This means that the measures that are supposed to support black business are punishing the same businesses for not being paid. It is like a vicious circle,” he says.

Matabane says the solution should be “the implementation of the spirit of the current transformation instruments and legislation such as the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment [B-BBEE] Act”.

This is the government’s policy to advance economic transformation and enhance the economic participation of black people in the South African economy.

Matabane says most companies have now adopted a “tick-box approach”. “Some of the companies will be B-BBEE level one [which means the company is 100% black-owned] but when you look at the top structures of these companies, they don’t look like level one. If the situation does not change, there may be a need for the tightening of the legislation to accelerate socioeconomic transformation,” he says.

Lebohang Pheko, senior research fellow at Trade Collective, says B-BBEE has failed to help black businesses. Many of the platforms that were created were co-opted, she says, adding that, “it has become the notion of black businesses being politicised and diluted”.

Pheko says that instead of mass transformation, through which black consumers can decide where and how to consume from black retailers and manufacturers, transformation has been reduced to a “cabal” of a few very wealthy individuals and families at the expense of any transformative shift.

She says, since the dawn of democracy, South Africa has not been able to make headway in a meaningful way; therefore, there is a structural issue that the country needs to address.

Pheko adds that, in addition to lacking support, black businesses struggle with accessing funding and resources when compared to white businesses, which can benefit from intergenerational wealth. “It’s so much easier to take risks if you have a trust fund to help you stay afloat … black people do not have wealth as a lineage”.

Duma Gqubule, an independent economist, questions the commitment of the government to real transformation of capital to benefit the black majority in South Africa. “We are not serious about anything.”

Gqubule says the government needs to work to increase the participation of black people in the economy, or else society will become unviable.

Instead of B-BBEE in its current form, he has called for empowerment quotas. “We need to have quotas for black representation on boards, black women representation. Banks must disclose all their lending and tell us how much of it goes to black businesses,” Gqubule says.

Tshegofatso Mathe is an Adamela Trust business reporter at the Mail & Guardian