(John McCann/M&G)

South Africa is host to at least 3.7-million migrant workers, whose incomes have been disrupted by the slowing down of economic activity. The lockdown in March resulted in a sharp decrease in remittances because of the strict regulations imposed by the government, which left many migrant workers without employment.

One month after one of the most stringent lockdowns in the world was imposed, remittances from South Africa dropped by about 80%, according to information from local money-transfer companies Mama Money and Hello Paisa.

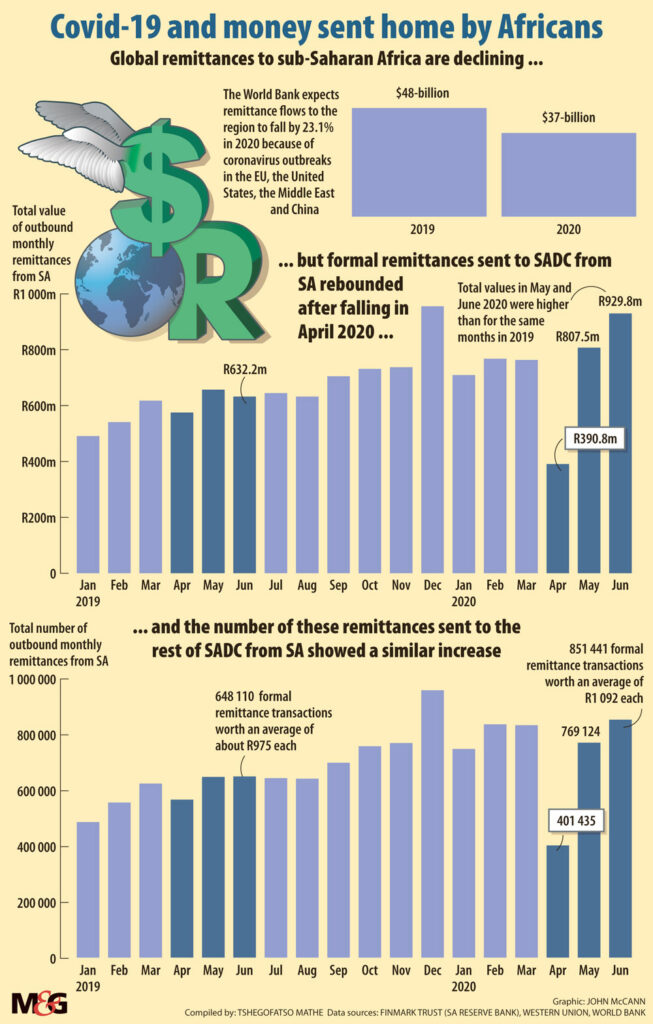

The World Bank estimated that global remittances would decline “sharply” — by about 20% — in 2020 because of the economic crisis induced by the Covid-19 pandemic and accompanying lockdown. The bank said the decline, which would be the “sharpest in recent history, is largely due to a fall in the wages and employment of migrant workers, who tend to be more vulnerable to loss of employment and wages during an economic crisis in a host country”.

For migrant workers in South Africa, the situation is even worse back home. According to research by nonprofit organisation FinMark Trust, which works to make financial markets work for the poor, the country has 3.7-million migrants living in the country, of whom 80% work in informal jobs. Many of these migrant workers come from Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Lesotho, Eswatini and Malawi.

FinMark Trust’s latest report shows that between December and April this year, monthly remittances declined from R955.5-million to R390.8-million. This was a 40.9% decline, dramatically affecting what people like Esther Costa, a Mozambican woman who has been working in South Africa for 22 years, could send home.

This week Costa was begging people to get their hair braided on Kerk and Eloff streets in the Johannesburg central business district. On the day the Mail & Guardian speaks to her, she only gets one customer, who will pay her R70 for cornrows. Although lockdown restrictions have been relaxed and hair salons may now operate, Costa is not making enough money to support her two children and send money back home in Mozambique.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

She says when things were normal she would usually send R1 000 home to support her mother, who is a pensioner. “When we have money, I send [some of it] home. But now it’s difficult to send money because people are not coming to do their hair [because of Covid-19]. Even the little I get, I have to use it to ensure that there is food at home for the kids.”

Costa’s story is not unique. Together with millions of South Africans, many migrant workers have lost their source of income due to the lockdown regulations.

Costa tells the Mail & Guardian that she is going to use the R70 to commute to Alexandra. This taxi round-trip now costs R40. The rest of the money she will have to buy food for her two children, leaving nothing.

According to the World Bank, there are two types of remittances: official and unofficial. The bank’s numbers mostly track the official remittances from banks and money-transfer companies. Remittances are a huge industry in Nigeria, for instance, where they reached $25-billion in 2018 — almost four times more than foreign direct investment and official development assistance combined. In Lesotho, remittances amounted to 16% of the country’s gross domestic product.

The bank noted that the sharp decline in money transfers could have a catastrophic effect, especially on rural livelihoods.

Gerhardus van Zyl, a labour economist at the University of Johannesburg, says the decrease in remittances indicates the weakness of the South African economy and that it is also a reflection of the steep increase in unemployment.

Van Zyl says many migrant workers in South Africa have lost their jobs, either in formal or informal sectors. He notes that the decrease in the flow of money will have a terrible effect on the economies of other countries in terms of consumer spending, because some people in these countries depend heavily on remittances from family members working in South Africa, using the money to buy their necessities.

Bryan Kelmus, from Harare, Zimbabwe, says that he has had to look for other means to make money since gyms were closed on March 27.

Kelmus works as a freelance sports physiotherapist and coach. For him to get paid, he has to work. He is the main breadwinner at home — and he sends money home to support his daughter and mother.

“I used to send R5 000, now R1 000 is the little I can afford,” he says.

But last month Kelmus could not put any money together to send home. He says his family understands. “Even back in Zim, things are really tough. We have been in this constant battle of not having enough. So my family has started to understand. They cannot even blame anyone. We are Christians; we have faith — we know that this is a phase and it will pass,” he says.

Kelmus explains that his group of friends now use a 101 or 011 formula to determine when they can eat. A “101” means you skip a meal in the afternoon; “011” means you skip a meal in the morning, and then you need to find what to eat in the afternoon and in the evening.

Meanwhile, the majority of the mainstream money-transfer companies have been hit hard. According to Western Union’s presentation of its second quarter financial results, the company’s revenue declined by 17%, to $1.1-billion, in the second quarter. The company said the primary reason for the decrease is because of lower transaction levels resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Other emerging companies, such as Mama Money and Hello Paisa, said they noticed remittance outflows for certain countries dropped by as much as 90%. Hello Paisa said it has seen a decrease in the average amounts that customers are sending to their loved ones back home. But, as the lockdown regulations are being relaxed, there is a rebound on the horizon as companies notice an uptick since April’s plunge in remittances.

For now, migrants such as Takudzwa Mutsipa* who usually sends money home to Bulawayo in Zimbabwe, say they have not been able to support their families. As a hairstylist, Mutsipa pays for his sister’s university tuition and supports his mother, but after a 50% salary cut, this has been near impossible.

Jo Vearey, the director of African Centre for Migration & Society at the University of the Witwatersrand, says migrant workers are particularly affected because they did not receive financial support from the state. She added that, as a result, responses targeting non-citizens are taking place, mostly parallel to state initiatives.

*Not his real name.

Tshegofatso Mathe is an Adamela Trust business reporter at the Mail & Guardian

World Bank highlights importance of recovery

“Remittances are a vital source of income for developing countries. The ongoing economic recession caused by Covid-19 is taking a severe toll on the ability to send money home and makes it all the more vital that we shorten the time to recovery for advanced economies,” said World Bank Group President David Malpass.

According to the bank’s April report, remittance flows are expected to fall across all regions, most notably in Europe and Central Asia (27.5%), followed by Sub-Saharan Africa (23%) South Asia (22%).

This drop comes after remittances to low-to-middle income countries (LMICs) reached a record $554-billion in 2019. Even with the decline, remittance flows are expected to become even more important as a source of external financing for LMICs, because the fall in foreign direct investment is expected to be even larger. In 2019, remittance flows to LMICs became larger than foreign direct investment.

In 2021, the World Bank estimates that remittances to LMICs will recover and rise by 5.6%, to $470-billion. The outlook for remittances remains uncertain because of the effects of Covid-19 and the measures to restrain its spread on the outlook for global growth.