Choosing a suitable home for your money is one of the most important decisions any individual can make, especially in times of volatility or uncertainty.

Over the past few years, investors have had to adapt their investment management strategies through the ebb and flow of the US-China trade tensions, but in 2020, amid the mounting pressure of easing these geopolitical tensions, the coronavirus took centre stage.

Within the first few months of the year, the outbreak of the pandemic thrust the global markets into uncertainty and unpredictability, which has tested investors’ ability to gain consistent ground.

In times such as these, humans often rely on their past experiences or gut instincts to make decisions, including where to invest their money. According to a new report by financial services provider Momentum, South African investors often base their investment decision on two emotions: fear or greed.

Momentum analysed the investment decisions of 23 390 investors on its investment platform, who have the option to choose from more than 1 500 funds.

The Momentum White Paper, which was released on Thursday, shows that this investment behaviour leads to South African investors frequently switching between top-performing funds, despite evidence suggesting that frequently chasing top performers does not guarantee strong investment returns.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Frequently switching between funds negatively impacts investments in the form of “behaviour tax”. This tax refers to a lower investment return as a result of an investor’s behaviour, like hastily switching funds because markets are falling, compared to portfolios that are bought and held.

“This essentially explains why following our gut instincts when investing often does not serve us well,” says Momentum’s head of technical marketing and behavioural finance, Paul Nixon.

In times of market turbulence, investors who switch their investments erode on average 1.1% per annum, Nixon says.

The report found that investors in the country start confidently that their investment decisions will result in profitable and consistent returns. This confidence is often short-lived as investors may overreact to good or bad news about their funds.

This results in investors becoming trapped in a cycle of fear and greed; when the market goes up, they are quick to rake in more than their fellow investors (often ignoring the fundamentals of long-term investing) and when the market goes down, fear kicks in and they become convinced that the market will not recover.

“A loss of capital is very scary to experience and can leave investors to throw in the towel and sit on the sidelines licking their wounds and missing out on the recovery. Similarly, the feeling of overconfidence that comes from being successful can lead an investor (or investment manager) to take on the risk that they really shouldn’t,” says Professor Evan Gilbert from the University of Stellenbosch’s Business School.

More than 44 000 switches by clients holding funds on the platform for the period January 2006 to December 2017 were analysed.

Of the sample of more than

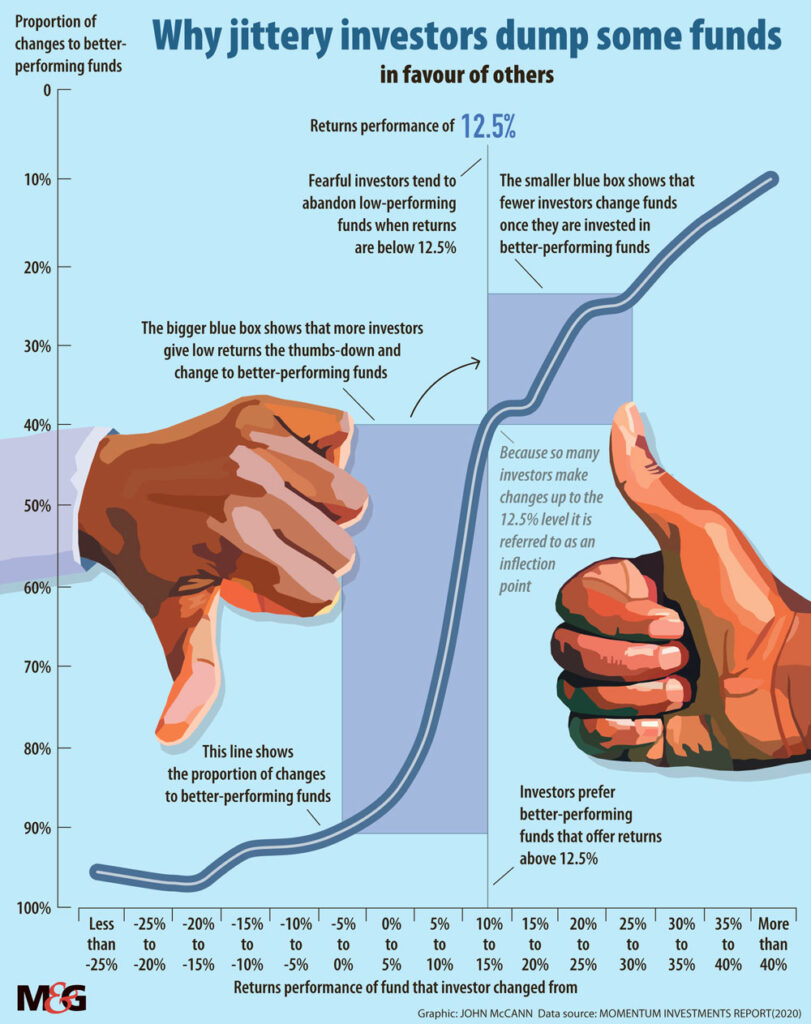

23 000 investors, 12 000 received a score based on how many switches fell either above or below a certain inflexion point, which is a practical application and reflects the level at which there is a sea change in investor behaviour.

Gilbert explains that this inflexion point means that as “investment returns dip below around 12%, investors become nine times more likely to change to another fund, their sensitivity to returns increases sharply and then later decreases.”

“The inflexion point, therefore, marks two distinctly different patterns of behaviour: to the left of it, investors fear painful losses and so sometimes increase the risk to avoid or make up these losses,” he says.

The study uses the term “greed” to describe investors making switches to better-performing funds above the inflexion point and “fear” to describe those switches made below the inflexion point.

Investors were also divided into different clusters depending on their investment behaviour. These clusters are avoiders, contrarians, market timers, anxious investors, and assertive investors.

The investment traits of the five different types of investors were seen during and after the 2008/9 global financial crisis. During the crisis, the avoider and anxious investor cluster were more likely to switch funds based on market performance. These two groups tend to avoid risk and are more likely to base their investment decisions on fear rather than greed.

The study found that there were fewer (less than 10%) investors in the contrarian cluster (who seemingly have a high-risk preference and a high tolerance of downside risk) who were active during the crisis, but during market recovery and during bullish market periods these types of investors were more active (more than 20%).

“The assertive investor cluster remained relatively constant during all economic cycles, reflecting their likely predisposition to overconfidence,” Gilbert says.

During a crisis like Covid-19, Gilbert says the avoider type of South African investor is more likely to dominate the market.

“Investors exhibiting this behaviour reduce their level of risk in times of crisis. They are also slow to revert to the painful experience of owning risky assets. This means that they will not benefit from the recovery after the crisis. This is probably the biggest source of the behaviour tax,” he says.