Default: African countries in debt include the Democratic Republic of the Congo at104.5% of GDP in 2020, Zambia 120% and Angola 120.3%. South Africa’s debt is likely to be 80.3% in 2021. (Luis Tato/AFP)

NEWS ANALYSIS

The Covid-19 pandemic is pushing low- and middle-income countries into debt crises and there is concern about what this means for development in the context of climate change adaptation, resilience and mitigation in the Global South.

The threat of more defaults provides an opportunity for multinational creditors to change the architecture of the global financial system.

Zambia became the first African country to default on its debt in 2020 when debt reached 120% of GDP. The Democratic Republic of the Congo and Angola reached 104.5% and 120.3% respectively in the same year.

The national debt of South Africa was about 62.15% of GDP in 2019 and is now forecast to be 80.3%, down from 81.8% in October. South Africa’s nationally determined contributions (NDC), released recently for public comment, are based on the condition that financial assistance becomes available for the country to decarbonise, in line with its low emissions strategy.

According to the United Nations, “Nationally determined contributions are at the heart of the Paris Agreement and the achievement of these long-term sustainable development goals. NDCs embody efforts by each country to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change.”

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) improved its forecast for South Africa upward to 3.1% this week but economists say the country is not out of the debt woods.

Global solidarity

The African Development Bank reminded the IMF at the World Bank spring meetings, which started on April 5, that Africa’s climate adaptation costs will reach $50-billion by 2040.

“Globally only 10% of climate finance goes into adaptation and Africa receives only 3% of global climate finance,” said the bank’s president, Akinwumi Adesina. He said that 10 of the top 12 countries most at risk of droughts are in Africa, despite the continent recording the least greenhouse gas emission.

“Africa needs global solidarity on climate change. Solidarity to boost Africa’s resources and capacities to adapt to climate change. Solidarity with nations to secure them against catastrophic climate risk events and damage,” he said.

Large polluter countries have failed to acknowledge financial accountability for the loss and damage from climate change in the Global South, despite attempts to put it on the table at the Conference of the Parties (CoP) every year.

High debt levels in Africa and underdevelopment are among the main reasons that the African Ministerial Conference on Environment believes wealthy, developed countries should pay their share for present and future damage as a result of their carbon and other emissions — particularly if these countries are investing in mitigation measures to align with the Paris Agreement.

Transition finance

“The decline in public finance for mitigation and adaptation, with grant financing hovering at around 6%, is a real concern to African countries,” said Environment Forestry and Fisheries Minister Barbara Creecy at the 5th Ministerial Meeting on Climate Action held in March. “We note with concern that developed countries are stepping back from a commitment to 0.7% of GDP for development aid. Developing countries are facing a debt crisis. We will need solutions to financing climate action other than increasing developing country debt.”

The prickly issue of finance by the world’s superpowers has made climate negotiations difficult.

Creecy said the pledges by more than 450 public development banks in November 2020 were welcomed. Banks have been asked to align their lending practices with the real needs of developing countries for their long-term transitions to climate resilient and zero carbon societies.

“This will definitely include the need for transition finance. Ignoring the real needs of developing countries in this regard will result in the Paris Agreement’s goals not being achieved,” said Creecy.

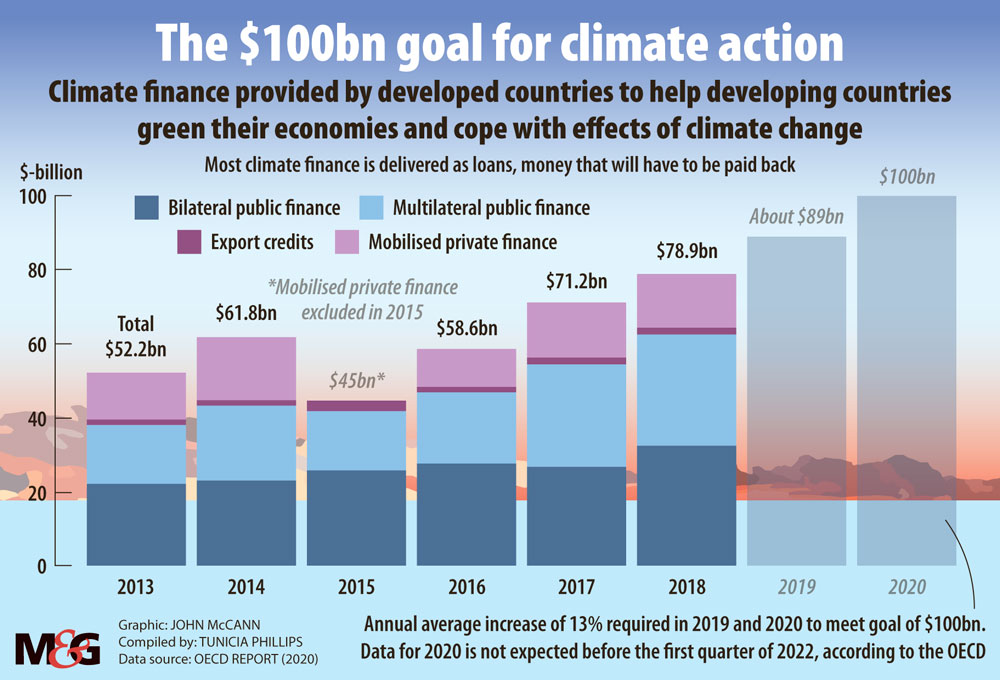

Climate experts have warned that if there is no debt, finance and loss and damage settlement before COP26, to be held in Glasgow on 1 to 12 November, it will also drain the trust that remains between wealthy and poor nations, and could undermine the summit. It has been 12 years since countries walked out of the Copenhagen CoP before developed nations committed to provide “scaled-up, new and additional, predictable and adequate funding” to mobilise jointly $100-billion a year by 2020 to address the needs of developing countries.

In the absence of accounting rules, it is near impossible to assess whether this commitment was met.

Inherent inequalities

The April 6 IMF and World Bank spring meetings will see the globe’s creditors decide how they will issue $650-billion of special drawing rights to over-indebted member countries.

This is a unit of account, valued in one of five major currencies, according to the size of a member’s economy. The last issue of drawing rights stabilised the global financial crisis sparked by the 2008 recession and was worth $250-billion.

But Aldo Caliari, a director of policy and campaigns and an expert in the IMF, World Bank and financial flows, says only a small portion of the funds will be for developing countries. “Only $220-billion would go to developing countries. We actually have argued for a much greater allocation of $3-trillion because we understand the needs of the developing countries are more in the range of $1-trillion.”

Jason Braganza, executive director at African Forum and Network on Debt and Development, said Africa is expected to record a $500-billion loss to the continent’s GDP through Covid-19 lockdowns and missed education opportunities. He said in a webinar that he was commenting on the outcomes of a “recent meeting” at the UN.

He believes the global political economy fails to see inherent inequalities and power imbalances that exist between debtors and creditors. “You know, in the case of Africa, the headline coming out of this pandemic is not actually the debt crisis but really from the African Economic Outlook report of 2021 that women and female headed households are likely to make the largest proportion of the poor post-Covid-19,” he said to a panel of high-level economists.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Debt-for-nature swaps

Previous solutions to addressing climate change and the debt burden in low- and middle-income countries have come in the form of debt-for-nature swaps, where a portion of foreign debt is forgiven in exchange for investments in environmental conservation and protection.

Caliari said: “More than two decades of that debt-for-nature swaps have reached under $3-billion in nominal debt, so we cannot expect to tackle neither the climate nor the debt crisis going at that pace.”

UN facility aims to boost Global South liquidity

The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) published a proposal inviting private creditors into the government bond markets of African countries, using a liquidity and sustainability facility (LSF).

The ECA said its purpose was “to assist member states have access to a facility that will strengthen their liquidity in the short term and restart growth in the longer term”. The ECA has partnered with asset management corporation Pimco to set up the LSF “that would lower governments’ borrowing costs by increasing the demand for their sovereign bonds.

Daniela Gabor, of the University of the West of England Bristol, said: “To avoid more debt relief, what you need to do is to encourage institutional investors to come into your government bond markets to provide liquidity and to do that, you have to subsidise them, so we’re looking at very concrete proposals to subsidise private investors.”

She also advised against putting special drawing rights through multilateral development banks.

But a former chief of sovereign ratings at S&P rating agency, Moritz Kraemer, believes over-indebted countries must get back to the table with the private sector and ignore the stigma attached to restructuring debt out of fear of being left out of capital markets.

Kraemer, who is now chief economist at Country Risk, said: “One third of the debt is with private creditors, but two-thirds of the interest burden is with private creditors, so they have to come into the boat, there is no other way.”

Tunicia Phillips is an Adamela Trust climate and economic justice reporting fellow, funded by the Open Society Foundation for South Africa