Photographer: Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images

In the five years since Anheuser-Busch InBev (AB InBev) closed on a $100-billion merger with South African Breweries (SAB), the Belgian multinational’s share price has plummeted while its competitors’ stock has gone up.

The troubles facing the world’s largest brewer are complex: For years beer sales slumped due to the changing tastes of health-conscious consumers. Having a presence all over the world has made AB InBev vulnerable to economic headwinds in emerging markets. The company has also been saddled with a pile of debt from the 2016 SAB deal.

Covid-19 has only added pressure. Another ban on alcohol sales, announced by President Cyril Ramaphosa last Sunday, will hit AB InBev’s South African business for at least another two weeks.

Experts have linked the AB InBev woes to the SAB deal, which the company’s then-chief executive Carlos Brito said at the time would cement its position as “a truly global brewer”. But the merger was not all it was cracked up to be.

The fall

AB InBev’s share price has fallen by more than 43% over the last five years. In the same period its competitors have seen their prospects brighten. Heineken’s share price rose 23.7% and Carlsberg’s share price went up by 67.42%.

Analyst Simon Brown said there is some complexity behind AB InBev’s share price spiral, but the true source of the decline is easy to pinpoint. “The simplicity is the SAB deal. The lockdown and the pandemic hasn’t helped … But of course the decline in the share price predates that,” he said.

“The really big driver is that they paid a really vast amount for SAB and they took on a vast amount of debt. In the long term — five to 10 years — they will have paid off the debt and everything will be fine. But they simply chronically overpaid for the acquisition.”

According to AB InBev’s 2020 annual report, the company’s net debt was $82.7-billion by December last year. SAB was likely not worth the price tag AB InBev paid for the South African business, Brown said.

“When you are buying shares, there is truthfully only one thing that you control. And that is the price you pay. Future profits, future dividends, the future share price, the price that you are able to sell it — those are beyond your control.”

The AB InBev executives “got a little bit starstruck”, Brown said. “We see it often in mega-deals. The desire to do the deal overwhelms and good old-fashioned logic goes out the window.”

Alec Abraham, a senior equity analyst at Sasfin, agreed that the SAB acquisition is the reason for AB InBev’s share price decline. The deal exposed AB InBev to a volatile market, Abraham said.

Exposed

“When they made the acquisition, they were bolstering their emerging market exposure. And it came at a time, I think, emerging markets were performing very poorly from an economic point of view,” Abraham said.

“And what we’ve seen is that because the emerging market economies haven’t performed well, affordability has become a bit of an issue and they haven’t seen the kind of volume growth that they were hoping for.”

Abraham added: “It was unfortunate timing, maybe. But I think it was directly linked to the fact that they bought a bigger stake in the emerging markets and the emerging markets simply haven’t achieved what they had hoped for.”

At AB InBev’s first-quarter results presentation in May, Brito — who was replaced by the brewer’s North American division head Michel Doukeris in July — said it has been “a hard ride” in emerging markets over the last few years.

The company recorded a 10% decrease in equity for the first quarter of 2021. This was primarily related to weakening currencies in emerging markets, including South Africa. By December 2020, the rand had fallen to R14.69 to the US dollar, down from the 25-year high of R18.46 to the US dollar recorded in April 2020.

AB InBev’s exposure in emerging markets also means the company is more vulnerable to Covid-19’s impact in these regions, Abraham noted.

Brito said: “When you think about Covid, our industry was one that was hardest hit … We had businesses in Ecuador, Peru and South Africa that were shut down for two months or more. And we continue to have restrictions.”

According to the presentation, its South African business was significantly impacted by the one-month ban on alcohol sales in January. Though the company saw strong consumer demand once the ban was lifted, sales volumes were flat compared to the first quarter of 2019.

After the first alcohol ban, revenue and volume from the South African market declined by more than 60%. Last year AB InBev chose to take a $2.5-billion impairment charge in light of heightened business risk in South Africa.

AB InBev’s 2020 annual report emphasised the company’s view that alcohol bans “significantly damage the South African economy, threaten the over one million livelihoods at stake throughout the alcohol industry’s value chain and entrench illicit alcohol trading, which has devastating consequences”.

The company attributed last year’s 29% decrease in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda) in Europe, the Middle East and Africa to the impact of lockdown on on-site alcohol consumption as well as the “three outright government-mandated bans on the sale of alcohol over the course of 2020 in South Africa”.

Recovery

However, AB InBev’s first quarter results signalled better performance, with the company forecasting that in 2021 Ebitda would grow between 8% and 12%, based on its analysis of the pace of market recovery.

The company had not factored in any full operational shutdowns such as another alcohol ban in South Africa, Brito said.

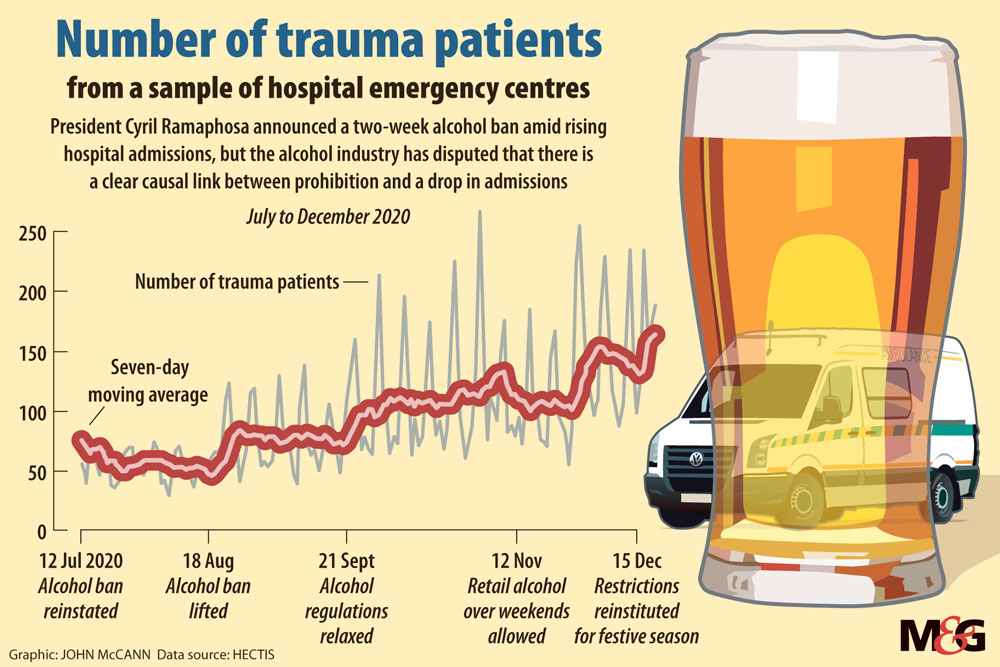

But the latest two-week alcohol ban, announced as part of the government’s efforts to slow down the rate of hospital admissions, came as existing measures were not enough to contain the spread of the doubly contagious Covid-19 Delta variant.

SAB is heading to court to have the alcohol ban overturned. “There is no scientific link that the consumption of alcohol raises the risk of contracting Covid-19, especially if alcohol is consumed safely and responsibly in the comfort of one’s home,” SAB said in a statement announcing the court action.

The statement added: “The current ban, which is unsubstantiated by robust scientific evidence, has been implemented at a time when the industry was already gearing itself for future stability and was ready to play its part in the country’s economic recovery.”

Last year SAB withdrew R5-billion in investments in the wake of the Covid-19 alcohol bans. Last month, weeks before the fourth alcohol ban was announced, SAB said it had allocated a R2-billion investment to upgrade its South African operations.

In a statement announcing the investment, SAB’s vice-president of finance and legal, Richard Rivett-Carnac said: “The move to implement reasonable measures, as we continue to navigate the pandemic, is a welcomed signal that we can expect to see more consultation in the future and that blanket bans will be a thing of the past. Further collaboration will provide the required confidence boost needed in order to attract further investment to the country.”

As long as emerging markets struggle to recover, there will continue to be pressure on AB InBev’s share price, Abraham said.

“Despite the fact that we are seeing a rally in commodity prices, I think you will need more sustained growth in emerging markets … And I think emerging markets are going to have moderate recovery compared to developed markets, because they don’t have the same resources.”

However, Abraham said, “if the stars align” emerging markets can still be a source of growth for AB InBev. “I think it would be a huge step to go back on that SAB deal and get rid of the emerging market exposure. Because the prospect, if things work out, is just so great.”

At the time of publication, AB InBev had not responded to questions from the Mail & Guardian.