Photographer: Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images

To the relief of the alcohol industry, which has been hit by lockdowns and the recent looting and arson in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng, the ban on liquor sales has been lifted. The end to the all-out booze ban is also good news for grocery stores, which, over the past two decades, have grown their stakes in the alcohol business.

On Thursday this past week, Pick n Pay chief executive Pieter Boone urged President Cyril Ramaphosa to lift the ban, which was instituted a month ago in the face of the third wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“In normal times, many independent shopkeepers depend on responsible liquor sales to sustain their businesses, and will not survive another prolonged ban,” he said in a statement.

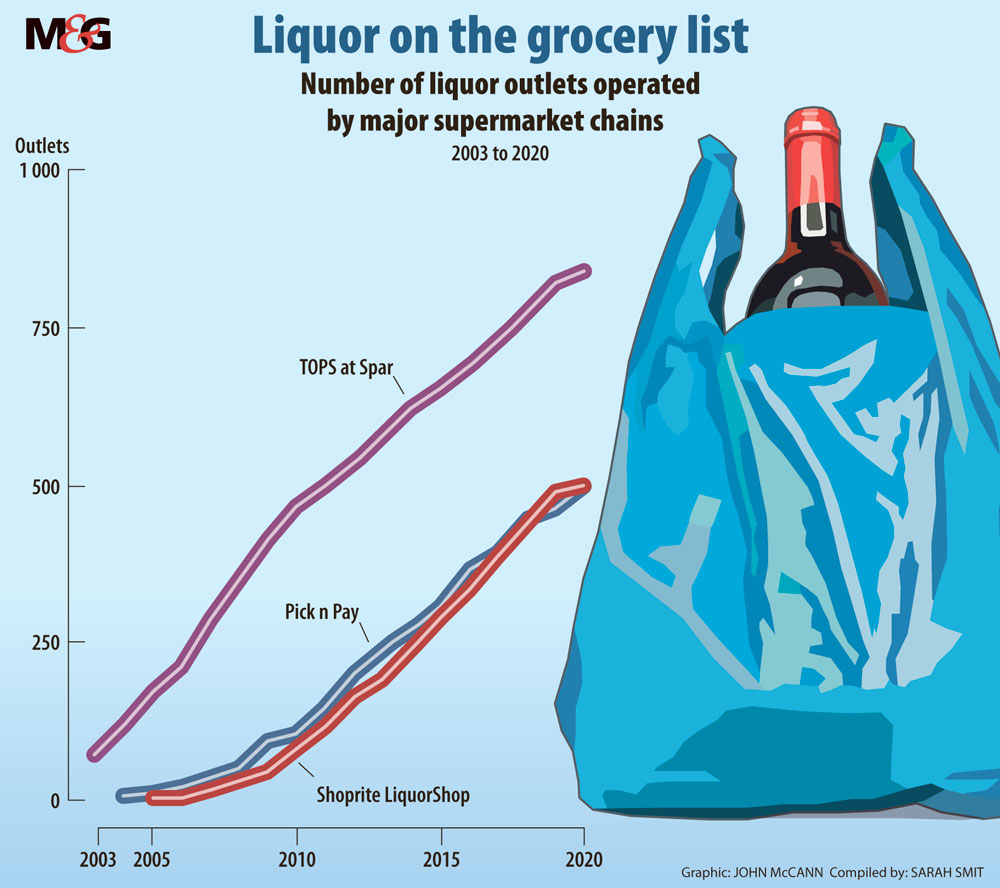

Pick n Pay, like other grocery retailers, has rapidly expanded its liquor business since the early 2000s. Recent blows to the alcohol trade have exposed just how central alcohol has become to retailers that once saw their trolleys only filled with food, analysts say.

Body blows

In their pleas to the government to lift the ban, alcohol manufacturers and retailers leveraged the negative effect of looting — ignited by Jacob Zuma’s supporters angered by the former president’s incarceration — on their businesses.

Boone said the arson and pillaging in mid-July dealt “a further body blow” to traders. The South African Liquor Brand Owners Association, which represents major alcohol manufacturers such as Distell and Heineken, said more than 200 of its members’ stores in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng were the target of attacks.

According to Pick n Pay, 76 liquor stores were severely damaged during the violence. Shareholder announcements show that 62 of Spar’s TOPS stores and 54 Shoprite LiquorShop outlets were also hit.

Ramaphosa yielded to calls by the alcohol industry, announcing the unbanning on Sunday night. He also said the payment of excise taxes by the alcohol sector would be deferred for three months “to ease the burden on the sector as it recovers”.

Pick n Pay liquor stores lost 209 trading days because of the lockdown restrictions in 2020. As a result, the retailer’s annual results show that liquor and alcohol sales were down by 31%. TOPS reported a 17.8% sales drop for the year. Sales in Shoprite’s liquor business declined by 21.8% in the second half of the year.

But even as these retailers took a knock to their sales, each has chosen to expand their liquor offerings. Pick n Pay is planning to open 47 new liquor outlets in 2021.

In 2020, Spar added 20 new TOPS outlets. In six months, Shoprite opened 26 new LiquorShops — one store for each week of the reporting period — and closed three, bringing the total number of stores to 541. The group confirmed it would open at least 19 more stores in 2021.

Woolworths has also recently entered the liquor game, launching its first standalone alcohol store in Johannesburg in May.

Retail analyst Syd Vianello said that once Spar got into the liquor business in about 2003, the other retailers were sure to follow.

“Its competitors could see exactly how well Spar was doing,” he said. “They realised they could jump on the bandwagon and establish liquor stores by extending their brands.”

Booze cruise

David Shapiro, the deputy chair of independent banking and financial services group Sasfin, agreed that booze was good business for grocery retailers.

“Lots of people buy liquor and there are very big margins. It’s a very vibrant market.”

Shapiro said that as a result of historically strict liquor laws, South African supermarkets were limited from following global trends of food retailers opening separate alcohol outlets.

Grocers were only allowed licenses to sell wine in 1989, but they were prohibited from selling liquor. The 2003 Liquor Act gave them license to sell it for consumption off the premises.

When the 2003 amendments were being considered, Pick n Pay said in its submission to parliament that the retailer’s market research indicated its customers “would like the range of liquor sold in our stores expanded from wine to include beer and spirits”.

“This is an internationally accepted norm. The alcohol content of beer is lower than wine, and it is recognised as an accompaniment to food, along with wine. Beer is accepted internationally as a consumer item and is sold, together with spirits and wine, in supermarkets around the world,” it said at the time.

Pick n Pay also contended that in preceding decades liquor manufacturers had monopolised the sale of their products: “They successfully lobbied the previous government to ensure that the liquor legislation reflected and protected their interests.”

After fresh legislation was enacted, Pick n Pay took advantage, opening 13 liquor stores by 2005.

“These outlets have also proved to be popular and we intend growing this format in suitable locations,” the retailer said in its 2005 annual report.

Over the next five years, Pick n Pay grew this number to 105. In 2020, there were 501 Pick n Pay Liquor stores.

Between 2000 and 2003, when Pick n Pay was not yet allowed to sell liquor, its share price remained relatively muted. It climbed steadily from the beginning of 2004. The grocer’s share price dropped steeply in 2020, when alcohol sales were restricted.

“You can see, if you need proof, of liquor’s impact on grocers, just look at the results. If you just want to see the impact of what liquor has done, look at how much it took away when they weren’t able to sell it. So you can see how meaningful it is for them,” Shapiro said.

Vianello echoed this: “All you have to do is read the commentaries by the retailers over the last year about the impact that the liquor ban has had on their turnovers. Clearly, liquor is an integral part of the business.”