Three party leaders who previously spoke to M&G said they expected Ramaphosa to announce replacements for Transport Minister Fikile Mbalula

NEWS ANALYSIS

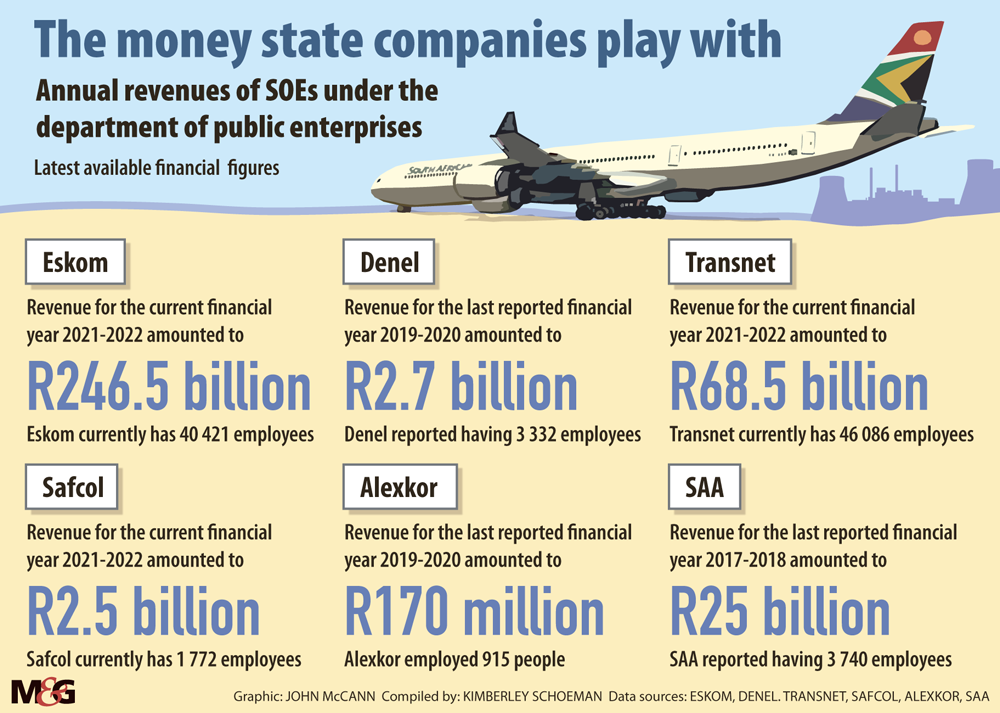

The future of the department of public enterprises (DPE), set up to restructure the country’s state-owned entities (SOEs) more than two decades ago, hangs in the balance.

In a move that could signal the department’s dissolution, the ANC has taken a resolution that state-owned entities — including economic albatross Eskom — should be moved to their relevant policy departments. This comes as Pravin Gordhan, the minister who has been at the helm of the department for the past five years, appears to be on his way out.

With most of the entities it oversees in states of disrepair, many have questioned the department’s relevance. Hamstrung by inadequate accountability and capacity, political meddling and ideological disagreements, it has failed to fulfil its founding aspiration: ensuring the country’s state-owned entities buoy, rather than burden, the economy.

The public enterprises department was officially established in 1999.

At that time, Eskom and most other state-owned entities still had healthy balance sheets and their restructuring was viewed as a means of maximising their economic impact. From 1995 to 2006, the power utility’s net profit margin averaged 12.2%.

The policy framework developed by the department and delivered by the then minister, Jeff Radebe, in 2000 underlined the importance of corporatising Eskom and unbundling its generation, transmission and distribution businesses into three separate entities — a proposal contained in the 1998 energy policy white paper.

But for about two decades Eskom’s unbundling was shelved, until it was finally resurrected under President Cyril Ramaphosa’s administration.

In the period preceding Ramaphosa’s presidency, the restructuring of Eskom and other state-owned entities proved tricky amid concerns about the effects of privatising electricity.

In 2001, trade union federation Cosatu opposed the Eskom Conversion Bill, which provided for the conversion of the utility into a public company, on the basis that it would pave the way for privatisation, a word the government had been careful to avoid.

A year later, Cosatu embarked on a national strike in protest against the privatisation of Eskom and other utilities. It was the first strike of its kind by the federation since the ANC came into power in 1994.

Complicating matters further was Telkom’s listing on the JSE, a move that was strongly opposed by the ANC’s other alliance member, the South African Communist Party (SACP).

At the time, Telkom’s listing was viewed by critics as the government’s rebuttal against labour’s anti-privatisation push.

In 2003, Telkom became the first major listing on the JSE of a state-owned company, marking a loss for the SACP. That year, the government began to revise its plans to privatise part of Eskom’s generation assets, although the utility’s restructuring was still on the table.

This was solidified after the ANC’s win in the 2004 elections, when it said it would not sell Eskom’s core assets.

That year, then public enterprises minister Alec Erwin announced the wholesale sell-off of state-owned assets was off the table, adding labour would in future be consulted on the restructuring of state enterprises.

Erwin also floated the idea of public-private partnerships for Eskom, Transnet and arms supplier Denel, a proposal that was criticised by Cosatu.

But by 2004, the government had a bigger problem on its hands: securing the country’s energy supply.

By that year, thanks to the country’s electrification drive, millions more people had access to electricity. Demand on the grid was intensifying, but Eskom had not built the capacity to shoulder this new burden. This was despite the 1998 energy policy white paper warning that growth in electricity demand was projected to exceed generation capacity by 2007.

In October 2004, the cabinet took a resolution that Eskom should build new power stations, marking the beginning of the costly Medupi and Kusile saga. The government’s intervention had come too late and 2007 saw the start of a 15-year load-shedding crisis, which proved an all too heavy burden on the country’s economy.

In 2010, then president Jacob Zuma appointed a presidential state-owned entity review committee. In its 2012 report to the president, the committee noted that in the 18 years prior there had been various efforts to reform state-owned entities. “The results and impact of some of these initiatives have raised more questions than answers,” the report said.

In the period that followed, with Eskom approaching a meltdown, little was done to restructure the country’s state-owned entities. It didn’t help that for much of that period, the country’s institutions were in the throes of yet another crisis — state capture, which had the inevitable effect of blocking reform.

A 2016 report by the national planning commission noted that years of policy uncertainty, opaque funding strategies, poor institutional accountability, politicised boards and mismanagement “have led to the chronic underperformance of some SOEs, and in some cases, near-collapse”.

When Ramaphosa came into power, stabilising the country’s state-owned entities was a priority. The president would later follow his predecessor’s lead and appoint a presidential state-owned enterprises council (PSEC).

To the chagrin of labour, but the relief of others, the president called for Eskom’s unbundling in his 2019 State of the Nation address.

Gordhan, the man overseeing Eskom’s unbundling, was directed by the president that his department formulate a special paper on the future of the utility. The paper noted that Eskom’s institutional transformation would be the largest undertaking by South Africa in a strategically important area in recent history.

Among the most pressing interventions outlined in the paper was establishing a separate transmission company within Eskom, the first step in the unbundling process.

In 2021, Gordhan said the legal separation of the transmission company would be completed by the end of that year. The distribution and generation companies would follow, with their separation expected to have been completed by 31 December 2022.

To give effect to the unbundling of its transmission division, a legally binding merger agreement was entered into between Eskom and its wholly-owned subsidiary, National Transmission Company South Africa (NTCSA), in December 2021. But, without the licences needed by the NTCSA to operate Eskom’s transmission division, its unbundling is yet to be completed.

In November last year, the department reported that it had met its key performance indicators related to Eskom’s unbundling roadmap. It had not achieved its indicators relating to increasing the utility’s energy availability factor or its electricity reserve margin.

The department had also not yet developed business plans for state-owned entities or established a restructuring unit. “The development of the business case to support the PSEC work in restructuring of the SOEs with the aim of stabilising ailing SOEs is still at its inception stage,” the department reported.

Speaking specifically on Eskom’s decline under the department, energy economist Lungile Mashele noted that the shareholder ministry is meant to provide oversight on increasing the utility’s reserve margin, improving its energy availability factor, procuring additional capacity and unbundling. “Eskom has failed on each metric and their shareholder has not held them accountable,” she said

Mashele suggested that the department may not have anticipated how costly and time-consuming Eskom’s unbundling would be.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

“There are many legalities such as a transmission licence, which has dragged on for over a year. There’s also the issue of how to handle Eskom debt and how it should be allocated between the new companies” she said.

“Issues to consider are also the funding of these companies in the absence of a revised tariff structure which would allocate a portion of the tariff to each entity.”

Those in support of moving state-owned entities to their relevant policy departments suggest that doing so may help the accountability issue, as they will no longer be torn between two ministers.

Others have pointed out that poor capacity across departments, as well as the other dilemmas that hamstring state-owned entities, means that shifting them around would have little effect.

Wayne Duvenage, the chief executive of anti-corruption outfit the Organisation Undoing Tax Abuse, noted that Gordhan inherited state capture’s problems. “But you would have expected that by now you would have seen robust turnaround strategies at every single entity … That is a leadership problem. The DPE [department of public enterprises] is the shareholder, why do we have this situation?”

The government’s many state-owned entity-related interventions, including the appointment of the presidential state-owned enterprises council, have created a state of confusion, Duvenage said. “We are stuck in this limbo of supposed state-owned entities operating on behalf of the state in complex, competitive industries, but without complex and competitive mindsets. So they will forever fail, because government is confused about its strategy.”

Iraj Abedian, chief economist at Pan-African Investment & Research Services, said the department of public enterprises has been “a spectacular failure”, adding that it has demonstrated no understanding of how businesses are run and that it lacks the technical capacity to turn state-owned entities around.

Abedian repeated a criticism often levelled at Gordhan — that he has a tendency to interfere in the governance of state-owned entities.

“Everything that he has touched, unfortunately, has gone south, so to speak. And the common denominator is his lack of understanding that business cannot be turned around by politics,” he added.

But, according to Abedian, the picture isn’t exactly much prettier at the department of mineral resources and energy. “They will take another few years to make their own mistakes. And, in the meantime, Rome is burning. The country is suffering. Jobs are being lost. Businesses are becoming bankrupt. The nation is frustrated.”

This view of the state’s capacity to turn around its utilities suggests they are caught between a rock and a hard place.

Another expert, who asked not to be named, echoed this sentiment, adding that given the scale of corruption any alternative models for the oversight of state-owned entities stand to go sour. “Any good thing is potentially bad,” he said. That said, moving state-owned entities to their policy departments could make life easier for them, he added.

Decrying the near-absence of reform since 2009, the expert added: “None of the restructuring plans have been implemented. A couple of years ago, there were all sorts of plans … There are inquiries, there are task teams, there are committees, there are proposals, but from 2009 onwards very little has been implemented.”

It may be impossible, the expert added, for the ANC to see through reforms. The department had not responded to the M&G’s questions at the time of writing.