Cop29 conference participants are reflected in a puddle as they arrive on day nine at the UNFCCC COP29 Climate Conference on November 20, 2024 in Baku, Azerbaijan. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

How much does using public transport, walking or cycling cut down on carbon emissions? COP29 was a good place to find out.

Set up at the Baku Olympic stadium, the part of the conference centre where we were (the blue zone) was just over 225 000m2, the size of about 28 soccer fields. So you walked like nobody’s business.

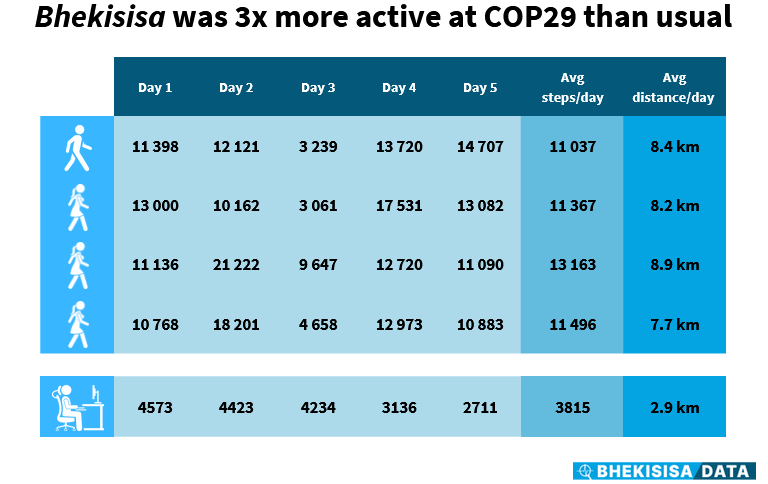

Bhekisisa had a team of four reporters at the climate conference. On average, our journalists walked eight to nine kilometres a day — something none of us do back in South Africa; we walked three times more than back home.

We all tracked our steps with apps on our phones and we then calculated how much carbon we saved.

We also used public transport (the subway and a bus for each journey) to get to the stadium.

But setting up efficient public transport systems, moving away from coal-fired electricity to cleaner energy like solar and wind power, and switching from cars and trucks fuelled by petrol and diesel to electric cars charged with green electricity, costs money.

And that’s what COP29 was all about: finding the money to pay for all of this.

The outcome was that richer countries will pay poorer countries $300 billion each year by 2035, because they’re responsible for most of the world’s historic carbon emissions that have led to the climate crisis.

But R300 billion is way too little — the Global South asked for $1.3 trillion.

“It is like going to an excellent doctor, and they tell you what the problem is but refuse to give you the medicine to cure it — that’s what’s happening, Omar Elmawi from Africa Climate Movement Building Space, told The Guardian. “There is no climate action without finance.”

Here are the stats of the Bhekisisa team’s walking and use of public transport — and what it means for climate change.

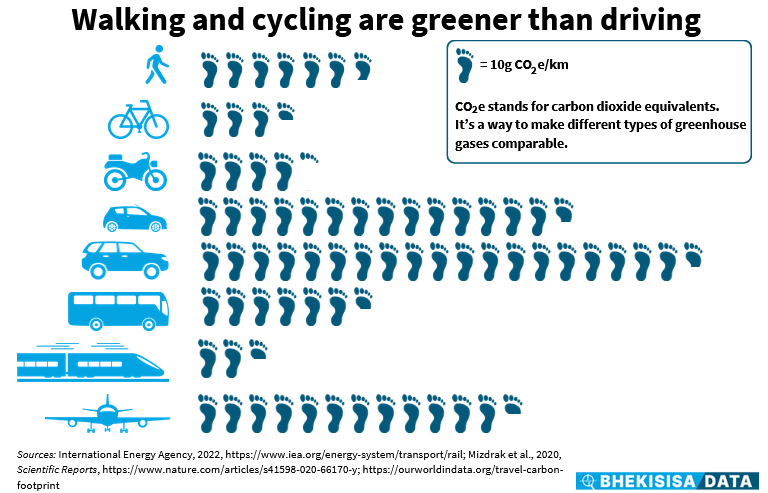

Everything we do — including driving in cars, riding a bike or walking somewhere — has a carbon footprint. This measures how many greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2) or methane an activity that burns a fossil fuel puts into the air, and gives an easy way to compare how emission heavy different activities are.

A big vehicle that runs on petrol or diesel, for example, produces about 193g CO2 per kilometre on the road. Riding a bike for a kilometre, on the other hand, gives out about 33g of the fuel, about half of what walking does.

The chemical process in our bodies that releases energy from glucose — the fuel we get from food — releases carbon dioxide, which we breathe out all the time.

The carbon footprint of active forms of transport such as walking and cycling is therefore linked to the type of food we eat, how it is produced and how much effort we put into the activity. For example, eating mainly food of which the production is emission heavy, like meat or products that are delivered from far, has a bigger footprint than eating mostly plant foods or produce that is farmed close to where you live.

Walking is more emission heavy than cycling, because it takes more effort to walk a kilometre than to cycle that same distance, and so your body needs energy — you have to eat more — to get there.

To get to the conference venue from our hotel, we walked about a kilometre to the nearest subway station, rode 9.5km on the train, hopped on a bus for 4.2km and then walked about another kilometre from where it dropped us to get to our desks at the media room.

This journey released an estimated 589g of CO2 per person. Going to the conference venue and back again later, each of us therefore released about 1 178g of CO2 a day.

If one of us had taken a taxi to cover the trip from our hotel to the media room and back, this would have released more than three times as much carbon dioxide than the total of the train, bus and walking, even though the total distance would have been less (because the route by road is shorter).

But, if three or four of us were to share a taxi, the emissions from driving would have been close to using public transport and walking, our calculations show.

The numbers show sharing rides is a good idea — whether you take public transport or carpool. A modelling study shows that subways shave off about 11% of the world’s carbon emissions, and in the 192 countries included in the study, the cities’ carbon emissions were half of what it would have been if the underground trains didn’t run.

It might not sound like much to save a few hundred grams of CO2 a day by swapping driving for walking or cycling. But research from the United Kingdom shows that replacing one car trip a day (of up to 16km) with cycling for 200 days saved half a tonne of carbon emissions per person a year — and by getting everyone to do that could save “a substantial share of [the] average per [person] CO2 emissions from transport”.

The four of us walked, on average, between 11 000 and 13 000 steps a day during our time at COP29. That works out to between eight and nine kilometres every day (because we don’t all take equally big steps).

About a third of our steps (translating to about 3km) was spent on walking to the train and bus that would take us to the stadium — the rest of the distance we covered in a day was from walking around at the conference to get to sessions, interview sources for stories, going to the bathroom or the coffee stalls for a break, or even just walking to the printers dotted around the media centre where we worked.

The point is, our calculations show we were about three times more active here at COP29 than what we usually are back at the Bhekisisa office.

And that’s a good thing.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) says 150 to 300 minutes’ activity a week, depending on how vigorously you exercise, can significantly lower the chance of developing heart disease, high blood pressure or diabetes.

In South Africa, deaths from conditions like these, which are often seen in people who are inactive, have increased substantially in a decade: from about 46% in 2010 to about 57% in 2020.

Walking or cycling instead of driving will help to keep us healthy, not only because we’re more active but also because it will slow climate change — which is making us sick, the WHO said at the launch of the Lancet Countdown report in the first week of the conference.

And it works the other way too.

Because physical activity keeps us healthier, it means we’ll go to hospital or have to take medicine less often. And with about 5% of the world’s carbon emissions coming from the health sector, we’ll be doing our bit to help keep the air’s temperature rise within 1.5°C of what it was in 1850 by simply getting off our chairs, to keep life on Earth comfortable. — Additional reporting by Sipokazi Fokazi and Zano Kunene.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.