Edinburgh University students protest against the false promise of "hybrid learning" to new and returning students on October 24, 2020 in Edinburgh, Scotland. (Photo by Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images)

An online hour-long lecture takes about eight hours to prepare. This is according to academics who found that with the move to online learning, they gained extra work, with some reporting suffering from depression and anxiety because of the workload.

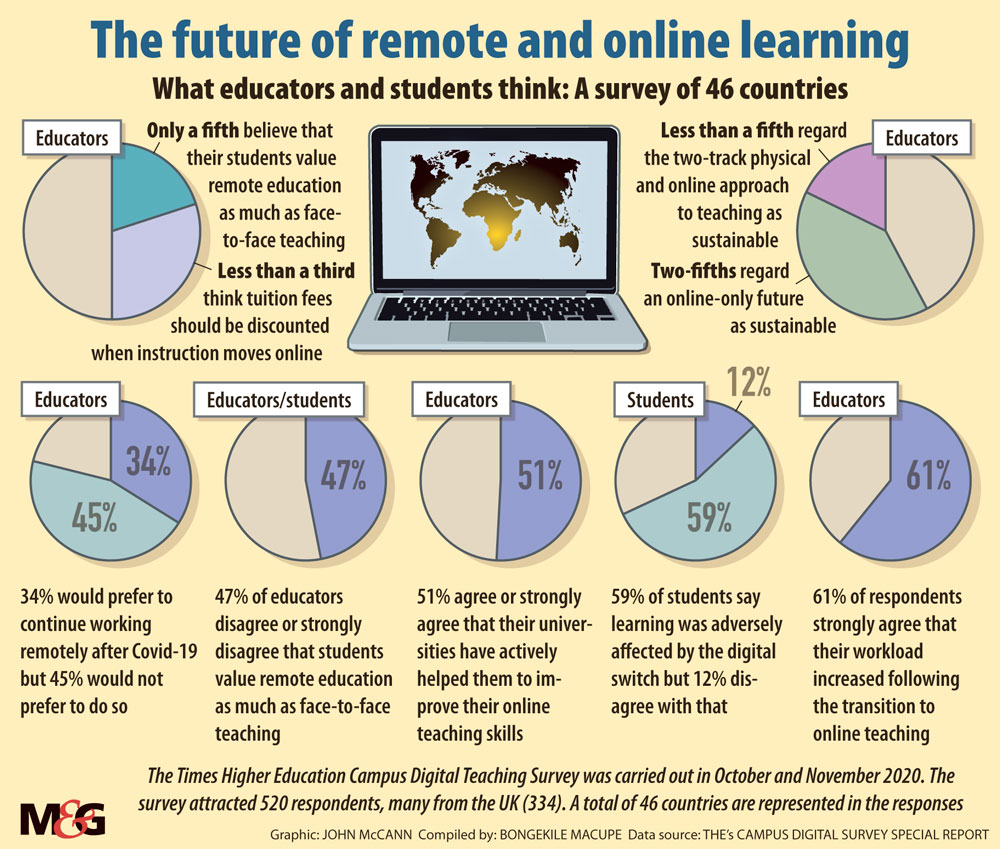

These are some of the findings in The Times Higher Education: Digital Teaching Survey, which was carried out in October and November last year and involved 520 respondents from 46 countries on six continents. The majority of those who participated — 334 — are from the United Kingdom.

The global survey into the effect of universities of moving to online teaching showed that about a third of respondents had no experience of online teaching before the pandemic and others only found out about platforms such as Zoom or Microsoft Teams when they suddenly had to use them.

Mental health was also not spared — lecturers reported going into deep depression and developing anxiety as the result of the workload.

According to the survey, 36% of the respondents said they had no knowledge of teaching online before the pandemic, with 26% saying they had a reasonable or a lot of experience.

A majority of respondents, 47%, said their university had assisted in the transition from contact teaching to online, while 33% said they had not received any support. In this regard, lecturers spoke about how they battled with internet connectivity and that it took a long time to get help from the university.

“A social science lecturer [from the UK] had to battle for six months to get institutional support with internet access, since broadband is unavailable in their area. They also had to wait five weeks for a new laptop, during which they had to work on their phone; this ‘affected my eyesight, as well as my neck and back’,” the survey noted.

The survey also shows that some students were disadvantaged by online learning because they did not have access to the internet and computers at home.

“Some were using their mobile phones for internet access, but some apps didn’t work well on phones,” reads the survey.

Academics from North America and Australasia indicated that their students did not receive any training in online learning; institutions assumed students were tech-savvy and would manage.

Some of the academics said the training of students was left up to them to navigate even though they did not have full knowledge of the systems. This led to lecturers being inundated with emails from students who were anxious about the online learning systems and falling behind on their studies.

Sixty-one percent of the academics said their workload had increased since the shift to online learning, while 28% said nothing had changed. But the survey found that views differed across disciplines, regions and according to the academics’ ranks.

“Everything online takes considerably longer,” said a South Africa-based senior lecturer in life sciences. “Online marking is a nightmare. Marking a basic test went from eight hours to five days. I had to work late each day and every weekend for several months to just keep up with my teaching.”

Some academics reported that their mental health had suffered because of the move to online — and because of their managers’ expectations.

A UK lecturer complained of feeling trapped in front of the computer all the time and the constant emails did not improve the situation. This triggered mental health episodes.

“ [The] lecturer suffered, for the first time in their life, with anxiety and an eating disorder, resulting in several weeks of sick leave,” the survey states, adding that the lecturer attributed this to a lack of institutional and financial support coupled with increased demands.

One academic reported having a breakdown and suicidal thoughts and had to take two months off work because of severe depression.

According to the survey, responses differed based on regions and disciplines. A social sciences lecturer in Spain noted: “It is stupid to teach face-to-face, putting in danger students and yourself. Teaching under a mask is very difficult and, besides, I have a student with listening problems that would not be able to read my lips. Online, I can subtitle my words on the go.”

Others said they would be comfortable returning to contact teaching after being vaccinated.

In April last year the Mail & Guardian reported that a group of academics was opposed to online learning, with the main objection being that universities had not made data available quickly enough but expected lecturers to provide information online. Some lecturers did not have laptops at home and relied on the desktops in their offices. Using smartphones to teach was simply not a viable option, they said.

The M&G reported that many students, especially those from historically disadvantaged universities, were unable to learn online because they did not have laptops and data. Students funded by the National Student Financial Aid Scheme will receive laptops in March, but the department of higher education had promised they would get them last year.