Civil society organisations have received South Africa’s newly proposed greenhouse gas reduction targets with little enthusiasm. The lower end of the emissions range remains the same as the nationally determined contributions (NDC) set in 2015.

The targets put out for public consultations will form part of South Africa’s commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions at the UN climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland in November. The United Nations Climate Change Conference, also known as COP26, will be the first time that the Paris Agreement signatories gather to recommit to keeping global warming at less than 1.5°C higher than pre-industrial levels through emission reductions.

Watchdog Climate Action Tracker (CAT) said that it would likely change South Africa’s rating to “insufficient” from “highly insufficient”. A rating of “insufficient” indicates an increase of 3°C, while a “highly insufficient” rating will lead to a 4°C increase.

“The upper end is now 28% lower than in the previous NDC, the lower end is unchanged. Depending on whether one analyses the upper or lower level of the emissions range for 2030, South Africa’s updated NDC would be rated as insufficient at the upper level,” or compatible with a 2°C at the lower level,” the organisation said after assessing the updated proposed targets.

Speaking during a webinar facilitated by the Mail & Guardian, CAT senior climate policy analyst Claire Stockwell said countries are now in an important cycle where the shortcomings of the 2015 NDCs must be improved to align with science.

“Current NDCs as of November 2020 will lead to a 2.6°C degree warming by the end of century and the picture is more alarming when we look at policies in place now, it will lead us to close to 3°C of warming,” she said, adding that the calculations were based on new ambitions submitted before the December Adaptation Summit. “Even with the announcements that we had in December, we would still have a significant gap in terms of limiting warming to 1.5°C,” she said.

The proposed targets exclude the planned carbon-intensive economic zone in Limpopo and assumes that all of the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) capacity will be built — including 4 500MW of new coal and gas projects.

“These fossil fuel projects will lock the country into many decades of harmful greenhouse gas emissions and seriously hamper South Africa’s ability to meet ambitious emission reduction targets in the future,” said Robyn Hugo of the nonprofit shareholder activism organisation, Just Share. “And the controversial Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone project has not been considered in the NDC.”

Hugo bemoaned the new projects that will further add to growing inequality and global heating.

The zone will need a 3 300MW coal plant to power multiple industries. The project was recently temporarily halted to remedy gaps in the environmental impact assessment.

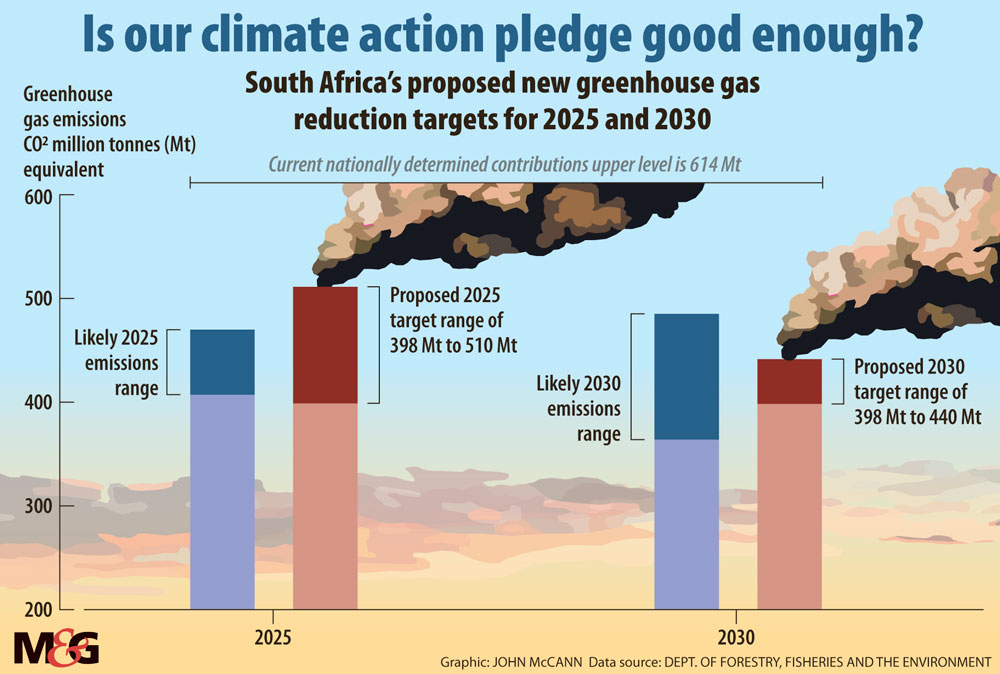

The NDC is structured around a two-cycle framework for mitigation policy. The five-year cycle will see the policy reviewed again in 2025. The new targets set out that in 2025, South Africa’s annual greenhouse gas emissions will be in a range between 398-million tonnes of CO2 equivalent and 510Mt of CO2 equivalent (a 17% reduction on the current NDC upper level), and in 2030 it will be between 398Mt to 440Mt of CO2 equivalent (a 28% reduction on the current NDC upper level)

UK high commissioner on climate encourages South Africa to bring more ambition to Glasgow

Reacting to the proposed mitigation efforts, John Wade-Smith at the British high commission to South Africa said that the globe needs to transition to low carbon four times faster than the current rate.

“People often – I think – criticise, quite rightly or question whether or not mitigation is the

only priority for the many in the developed world or developed economies which, it is obviously not,” he said. “The Paris [agreement] made it very clear that there are three pillars which include mitigation; but we need to strengthen adaptation and the impacts and we need to scale up support and finance that protects and restores nature and empowers inclusive action.”

He said these are the three pillars that the CoP presidency is determined to give equal priority as it works toward Glasgow.

“But it is clear that if we don’t get the mitigation targets right, if we don’t call the global action on a pathway that leads us to well below 2°C and closer limiting of 1.5°C, then we are not going to have the money or the adaptive capacity to manage what science tells us of climate impacts beyond 2°C, so mitigation is essential,” said Wade-Smith, who heads climate change and energy at the high commission. He said that the UK recognised that there is ambition in bringing the upper range down but called for more ambition at the bottom end which stays at a level above the 2°C target.

South Africa’s developmental economy is doing its ‘fair share’

The department of the environment meanwhile said that South Africa is a developing country and that there are considerations of equity.

“Yes we may be against the assessment by CAT, but we have also tested these targets against the climate equity reference framework which South Africa prefers to use because it takes into account issues of historical responsibility.

As a developing country we are the ones that have least contributed to the problem in terms of emissions over time and it is necessary that we make transitional change over time making sure that we do not compromise key sectors of the economy,” said the department’s director for climate change development and international mechanisms, Mkhuthazi Steleki. He further explained that the commitments were not conditional on only international support.

The targets are however reliant on several assumptions, with an expected boost in finance an important aspect. The key to these is that no new coal is procured beyond the current IRP and that there is a baseline of economic growth up to 2030.

It also assumes that the Green Transport Strategy — launched in 2019 by the department of transport to ensure that transport is environmentally friendly — is realised.

Energy efficiency programmes and the continued implementation of the carbon tax are also expected to progress in these assumptions.

But finance remains a sticky issue; South Africa will need to find $8-billion a year by 2030 to adapt to and mitigate climate change.

The 30-page document is out for public comment until 30 April and shows that in 2018 and 2019, South Africa received $4.9-billion in climate finance. This was predominantly through blended finance or loans, mostly to support mitigation projects.

“Greenpeace Africa’s research shows that for SA to be aligned with the Paris Agreement and to close the emissions gap, we need to submit a commitment that indicates what is required by science and that would be something that is in line with 288Mt of CO2 equivalent, so that would be a massive reduction from what environmental department has proposed right now,” said GreenPeace Africa climate and energy campaigner Thandile Chinyavanhu.

The 2020 Emission Gap Report found that global greenhouse gas emissions continued to rise for the third consecutive year in 2019, reaching a record high.

Even with the drop in 2020 as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, “atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases continue to rise, and the world is still heading for a temperature rise in excess of 3°C this century — far beyond the Paris Agreement goals of limiting global warming to well below 2°C and pursuing 1.5°C”, according to the report.

Tunicia Phillips is an Adamela Trust climate and economic justice reporting fellow, funded by the Open Society Foundation for South Africa