Counting the cost: Used plastic straws were collected at Khung Bang Kachao Urban Forest and beach during the Trash Hero initiative in Bangkok. In South Africa the move away from plastic straws may be motivated by consumer concerns. Photo: Mladen Antonov/AFP/Getty Images

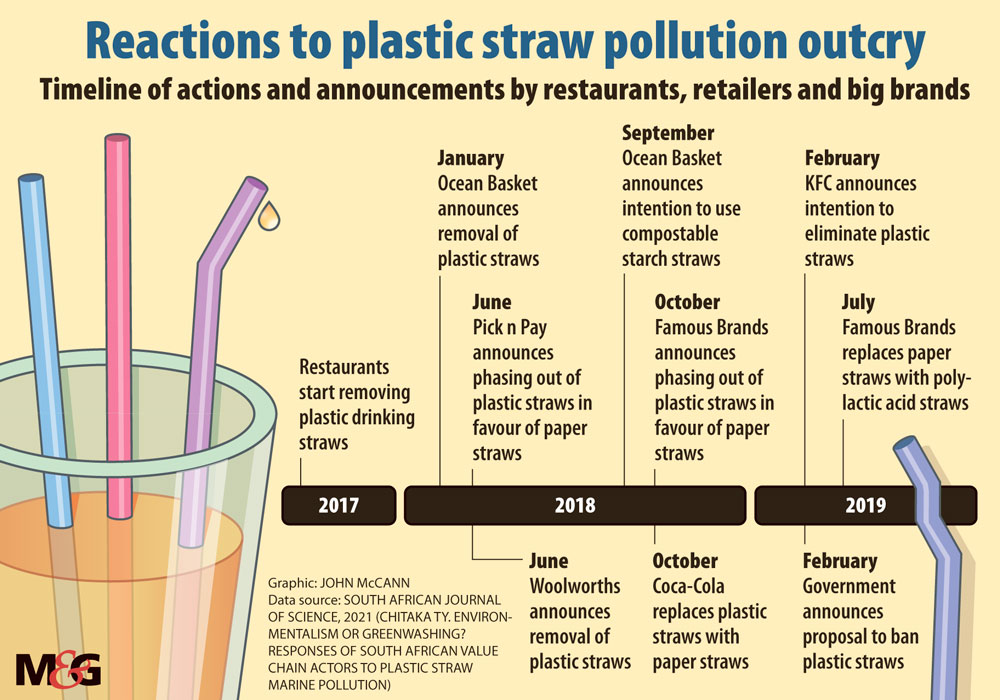

Ditching plastic straws was all the rage in 2018 in South Africa. Major retailers Pick n Pay and Woolworths announced they would be phasing out plastic straws from their stores in favour of paper alternatives to help curb plastic marine pollution from single-use plastics.

In October that year, fast food company Famous Brands followed suit, announcing it would replace plastic straws with paper straws across its franchises. Coca-Cola Peninsula Beverages decided to stop supplying plastic straws to customers such as retailers and restaurants. In 2019, there was a government proposal to ban straws, citing the ready availability of alternative materials.

Now, a new study published in the South African Journal of Science questions whether the straw bans by local brand owners, retailers and restaurateurs is motivated by a “true desire for environmentalism” or is instead, inadvertent or deliberate “greenwashing”.

In her research, Takunda Chitaka, of the department of chemical engineering at the University of Cape Town, found the seven value chain actors she interviewed were driven by a desire to meet consumer expectations. “This desire has led to the substitution of plastic straws with glass, paper and polylactide alternatives. However, the broader environmental implications of the alternatives are rarely considered.”

The paper details how the accumulation of plastic in the marine environment has been a global concern for decades, posing a threat to wildlife, humans and ecosystems. “Straws are one of the items which have been the subject of public outcry globally, with many consumer-led campaigns calling for material alternatives or the outright banning of plastic straws.”

This has led to a multitude of responses from companies and governments to reduce plastic straw consumption and waste generation. “Consequently, there has been an increasing popularity of alternative straw materials, both disposable and reusable, which are often touted as more ‘environmentally friendly.’”

Chitaka interviewed a brand owner, four retailers and two restaurateurs. Six had shifted away from plastic straws to alternative materials, with paper the most popular among retailers. Although most selected an option deemed favourable from a lifecycle perspective — paper — this was “coincidental”.

“For larger organisations (retailers and brand owners), the choice of alternative materials was a business decision to find a cost-effective way to respond to consumers’ concerns surrounding plastic marine pollution. While smaller value chain actors (restaurateurs) expressed a personal desire to reduce marine pollution, they were more vulnerable to false marketing regarding the environmental impacts associated with a product.”

Chitaka’s paper describes how Ocean Basket was the first major franchise to respond to the straw issue and is a good example of the complexity associated with such a decision. “Initially, they resolved to eliminate all straws from their restaurants in January 2018. However, as the year progressed, the franchise started offering paper straws and then announced their intention to start providing straws made from compostable maize starch.”

By July 2019, Famous Brands, too, had switched from paper to polylactide straws.

Regarding the effects on the environment associated with straw alternatives, the participants did not express consideration of any beyond marine pollution.

Bio-based plastics — plastics partly or wholly derived from biomass — such as polylactide straws have been growing in popularity as an alternative to traditional plastics.

“Retailers expressed concern in this regard, citing the amount of misinformation surrounding them, and in particular, the marketing of compostable plastics as biodegradable, which gave the impression they were biodegradable in all environments.”

The adoption of polylactide straws demonstrates the potential for inadvertent greenwashing, Chitaka writes. “The decisions of value chain actors should be based on robust scientific evidence to ensure their solutions address the problem they are trying to mitigate — in this case marine pollution — and that they are not engaging in burden shifting to other environmental compartments.”

Ocean Basket said it is reviewing all its in-store recyclables and is relooking its policy “with a view to balancing economic, social and environmental factors”.

Angelo Louw, of Greenpeace Africa, said the organisation is concerned about the scramble to find eco-friendly alternatives to single-use plastics. “Often, corporations tend to replace these with other single-use alternatives that are equally as harmful to the environment. Replacing plastic bags with paper bags, for instance, leads to an increased demand in paper, which elevates rates of deforestation.

“What we need is a shift from this once-off consumer culture of convenience that corporations keep force-feeding us, to distribution models that favour refill and reuse. We need to embrace the idea of zero waste more widely for these interventions to be truly impactful. The tendency of big corporations selling us environmentalism as some sort of exclusive and expensive fad needs to end. It will continue to be greenwashing for as long as big business tries to profit off environmental crises,” Louw said.

Woolworths said it has a vision of zero packaging waste to landfill, and for all its packaging to be either reusable or recyclable. This includes the commitment to phase out single-use plastic items from their stores.

Coca-Cola South Africa told the M&G that as a beverage company, it has the responsibility to help solve the global packaging waste crisis. “In 2018, we launched an ambitious sustainable packaging initiative called World Without Waste to collect a bottle or can for each one we sell by 2030. As part of this strategy, we recognise the impact of plastic straws on the environment and work together with our customers and bottling partners to reduce plastic use.”

In 2018, Coca-Cola Peninsula Beverages discontinued offering plastic straws to customers, suggesting biodegradable paper straws as an alternative. “Cost was cited as a major consideration by customers, and they chose instead to pursue other options,” it said, adding that the company stopped procuring paper straws and no longer supplies any straws to customers.

Kirsten Hewett, the head of corporate communications at Woolworths, told the M&G: “Plastics pose a significant environmental challenge at end of life if not disposed of appropriately. Single-use plastics are particularly problematic.

“As part of its Good Business Journey, Woolworths has a vision of zero packaging waste to landfill, and for all its packaging to be either reusable or recyclable. This includes the commitment to phase out single-use plastic items from their stores.”

The removal of plastic straws is part of this broader approach to managing plastic packaging, the retailer says, adding that to date, in addition to replacing plastic straws, it has replaced plastic cotton buds, lollipop sticks and in-store utensils with wood or paper alternatives.

“The straws and in-store utensils are sourced from Forest Stewardship Council certified paper or wood and 90% of all Woolworths foods packaging and products have Forest Stewardship Council certified paper, board or wood.”

Where possible, it has encouraged behaviour change. “There is a range of household products that include reusable straws, food storage containers, lids and utensils as well as a wide selection of reusable shopping bags, Hewett said.

David North, the chief strategy officer of Pick n Pay, said its replacement of plastic straws with paper straws has resulted in a reduction of eight million plastic straws per year. “Our customers were concerned about the impact of plastic straws on the environment. We replaced them with paper straws because these are more sustainable as a largely single-use product. We also find that acting effectively on consumer concerns about the environment often gives customers more confidence to take other steps towards more sustainable lifestyles, such as cutting out the use of straws altogether,” he said.

Lorren de Kock, the project manager of the circular plastics economy at World Wildlife Fund South Africa, said: “The findings from the study that the substitution of plastic straws with other materials due to consumer demands and least cost to the business is true. Up until this study, life cycle assessments have not been used as a basis to make decisions on which material or product delivery model is best for the environment.”

In reality, De Kock said, material substitution — replacing plastic with paper, glass or metal — is in most cases, not the best option.