New frontier: A variety of species occur in a deep ecosystem. The seafloor is threatened by mining even though there are enough materials on land and through battery recycling. Photo: Alexis Rosenfeld/Getty Images

Two years ago, a small unusual creature — the scaly-foot snail or sea pangolin — became the first species found only in deep sea hydrothermal vents to be listed as endangered because of the potential risks posed by deep sea mining.

To thrive in this environment, it has the largest heart relative to its size in the animal kingdom and iron-infused armour. It lives near fissures on the seafloor from which geothermally heat water discharges. These are east of Madagascar, an area in the Indian Ocean being explored for deep sea mining.

Cold, dark and subject to high pressures, the deep seabed is the planet’s “final frontier”, a largely unexplored world that scientists are starting to discover is bursting with life, according to In Too Deep, a report by World Wildlife Fund (WWF) International in February. It also exerts a major influence on the entire ocean ecosystem and the climate.

But the deep ocean is rich in metals and minerals, sparking a “gold rush” by companies and governments who want to scour the untouched ocean floor to enable the growth of electric vehicle batteries, solar panels and wind turbines in the coming decades.

The risks are great, according to WWF’s report. Deep seabed mining would have a destructive effect on fragile and untouched deep-sea ecosystems and biodiversity, which could have a knock-on effect on fisheries, livelihoods and food security and compromise ocean carbon, metal and nutrient cycles.

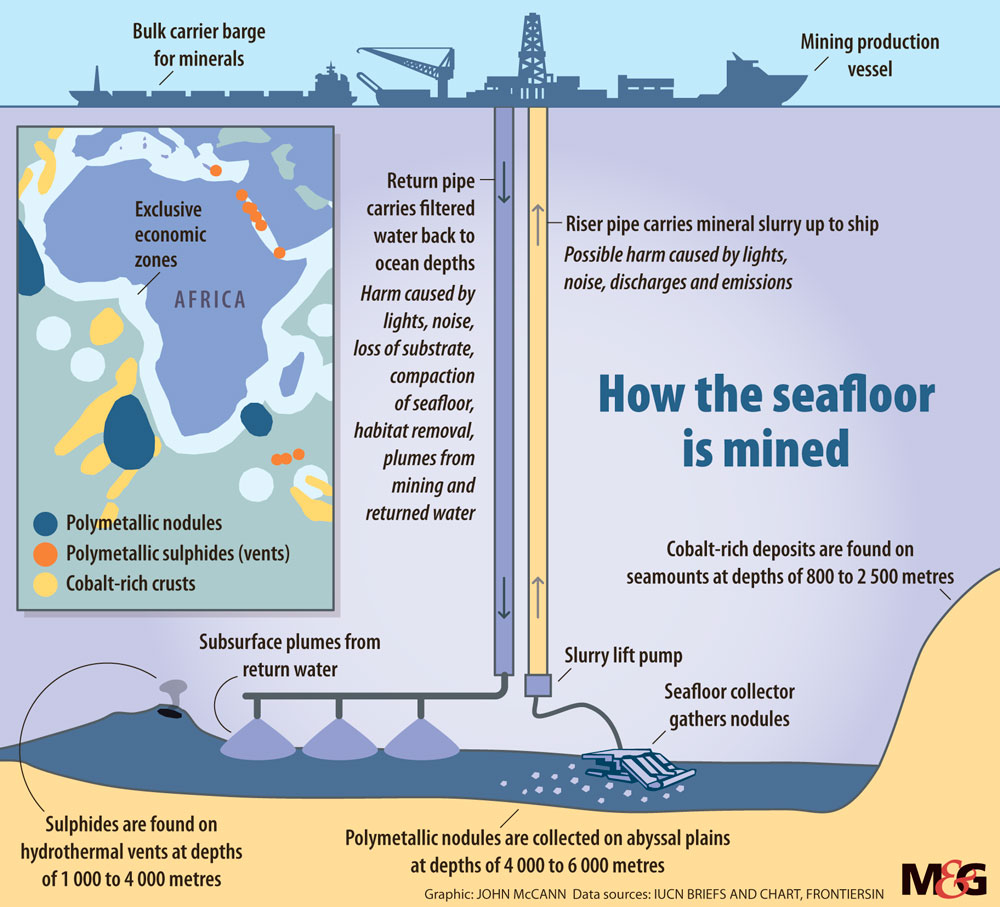

This mining would involve sucking up polymetallic nodules from the plains on the deep ocean floor, stripping cobalt crusts from biodiversity-rich seamounts (although the WWF says this is not yet commercially viable) and extracting polymetallic sulphides from hydrothermal vents, according to the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition.

More than 1.5-million km2 of international seabed — roughly the size of Mongolia — has already been set aside for mineral exploration in the Pacific and Indian oceans and along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), a United Nations multilateral regulatory body, regulates deep seabed mining while also having an interest in its financial benefits.

It has already approved 30 licences for the exploration of seabed minerals in areas beyond national jurisdiction and is working to adopt commercial mining regulations to enable applications from countries and companies for commercial mining permits in the international seabed area.

Last month, delegates to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN’s) global conservation summit voted overwhelmingly in support of a motion calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining and for the reform of the ISA.

This is until “rigorous and transparent” impact assessments have been conducted, the environmental, social, cultural and economic risks of deep seabed mining are comprehensively understood and the “effective protection of the marine environment can be ensured”.

The IUCN meeting is the world’s largest gathering of scientists, said Nishan Degnarain, an economic adviser to Mauritius. “If they are calling out seabed mining as fundamentally unsafe in the midst of the climate crisis, then these are important voices for governments to listen to.”

IUCN support for a moratorium is “very important and timeous”, said Jean Harris, the executive director of WildOceans. “Deep sea mining is a very destructive process that damages the seafloor and ecosystems that we are still discovering and finding populated by diverse but fragile biodiversity.

“Unlocking access to these areas for short-term economic gain by large industrial companies, without fully understanding these ecosystems and disturbing deep-sea processes that mitigate climate change and underwrite long-term health of the oceans and our plant, would be pure folly and is not in the interests of the global community.”

It is hoped, Harris said, that the ISA will now move to implement a moratorium “without further delays”.

Liziwe McDaid, the strategic lead for the nonprofit Green Connection, agreed. “The fact that the IUCN voted in favour of a ban on deep sea mining is important as it shows that the world is waking up to the need to protect our ecosystems. We need to acknowledge that we are part

of the ecosystem and if we destroy our planet, we destroy ourselves.

Hundreds of thousands of families rely on the coast for their livelihoods all around the coast of Africa and to ensure these livelihoods are sustainable, we need to protect our oceans,” she said, adding how this includes the need for a “ban on new extractives” and a focus on recycling and rehabilitation to drive a sustainable economy.

The benefits touted by companies for most seabed mining activities, including that these minerals are vital for the electric vehicle revolution, are “greenwashing”, said Degnarain. “There are more than sufficient materials available on land and through policies such as greater battery recycling,” he said.

The risks to Africa are particularly acute from the licenses issued in the Indian Ocean, which put several island nations and the east coast, including Seychelles, Mauritius, Madagascar, Comoros, Tanzania, Kenya and Mozambique, at great risk of losing their coral reefs, Degnarain said.

The ISA, he said, has not designed a compensation scheme large enough to cover any damage to African states. “If, over a period of 20 years, the underwater dust clouds produced hamper the growth of corals, mangroves and other coastal wildlife, then African states will have to pay for replenishment themselves.”

Large tracts of the Indian Ocean have been leased to India, China and South Korea. “There is no need for humans to be taking such large risks against the environment.”

[related_posts_sc article_id=”205805″]

The economic risks, too, will be large for Africa. “Seabed mining is focused on four main minerals, where African nations are some of the largest producers of high grade cobalt, nickel, manganese and copper. If these minerals are produced, countries like South Africa, Zambia, DRC and Gabon, will lose out as major producers.”

The sector is dominated by non-African nations. “Not one African nation holds any contracts from the ISA for seabed mining even though Africa is now surrounded by license claims in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.”

Instead of pursuing deep seabed mining, the continent has the potential to spearhead the electric vehicle revolution, through investing in 100% recyclable batteries, he said. “Africa can become a hub for safely and cleanly recycling used batteries … There are a range of new battery chemistries that do not rely as much on rare minerals. African nations can help spearhead the development of these sustainable batteries for the electric vehicle revolution.”

In recent months, almost 600 marine science and policy experts have signed a statement calling for a pause to deep-sea mining until there is sufficient and robust scientific information that shows it can be authorised without significant damage to the marine environment, and “if so, under what conditions”.

The same minerals that mining companies want to exploit are the foundation of deep-sea ecosystems, notes the WWF report. Given the slow pace of deep-sea processes, destroyed habitats are unlikely to recover within human timescales. “What has been created over millions of years would be wiped out in a day,” it warns.