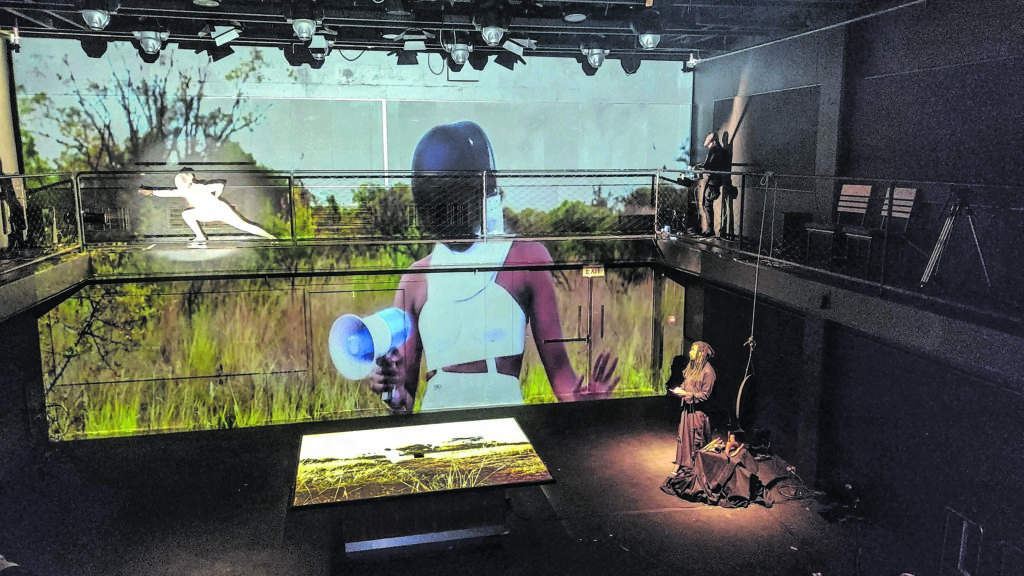

Jarring work: Mamela Nyamza’s Pest Control will be showing online at the National Arts Festival from June 25. (Ntombi Shabangu)

“A protest film, protesting that artists are not taken seriously,” is how Mamela Nyamza is choosing to describe her new work for the National Arts Festival, Pest Control, which launches online on June 25 this year. A teaser for the work, featuring the dancer in fencing and other forms of protective gear in both indoor and outdoor settings emerged this week.

She is, alternately, a pest being exterminated and a combatant not willing to take the onslaught lying down.

Judging by the teaser, it is a typically jarring work, Nyamza’s body a taut instrument of retaliation and defence; addressing personal tribulations while fitting right in with intensifying conversations about the role of and compensation for artists during the Covid-19-induced shutdown of the gig economy.

Mamela Nyamza’s Pest Control combines interior and exterior scenes. (Wilhelm Disbergen)

Mamela Nyamza’s Pest Control combines interior and exterior scenes. (Wilhelm Disbergen)

“The ministry has been so slow in working on the white paper,” says Nyamza, pulling no punches. “If they had done this years ago, they would have been able to distribute funds to artists at a time like this, like Sassa [South African Social Security Agency] does. All these institutions we have worked with have a database of what we have been doing and who we are — and these are institutions that they fund. They could have used that database and given all artists money in monthly stipends.

Don’t come with big documents for artists to fill [in] when we don’t have resources in our homes. Some of us come from where there is no wi-fi — in the bundus — how do you expect those artists to reach you?” She wonders aloud “what Miriam [Makeba] and Hugh [Masekela] would do” at a time like this, “because they were the loud ones”.

An acclaimed choreographer in the dance space, Nyamza’s new work also seems to allude to her firing as a deputy director at the State Theatre, which was precipitated by remarks she made during the opening of Dance Umbrella Africa in 2019. The confluence of her dismissal and the devastating sweep of Covid-19 — not to mention the department of sports, arts and culture’s lacklustre response to it — has only intensified the activist zeal underpinning much of Nyamza’s oeuvre, and is in full effect in Pest Control.

Perhaps more importantly, the pressure has forced her to confront new ways of making work. Although no stranger to filmed performances, Nyamza is intentional about terming her new work a film. “I didn’t think of it as performing for no audience,” she says. “I went out in nature with a film crew and created the work outside as an art film, and then went inside and used the juxtaposition of inside and outside. So it is an artwork. It challenged me, and allowed me to think metaphorically. A pest can also be a human pest.”

Responding to a range of issues raised by artists, the department of sports, arts, and culture, in a statement authored by spokesperson Masechaba Ndlovu, said the relief fund should be viewed as just that, “a mechanism to cushion the blow and not as indefinite sustenance.”

While Nyamza sought therapy and the comfort of the stage as her life was being torpedoed, fellow dancer Lulu Mlangeni sought recuperation and deliberation. “2020 was my year,” says the Standard Bank Young Artist for dance, running through the itinerary of what would certainly have been a breakthrough period in an already accomplished career. The National Arts Festival, at which she was to debut the work Kganya as part of a quartet, would have represented one of the many heights she was yet to scale for the remainder of the year and beyond.

As a result of Covid-19 restrictions on gatherings and what this would have meant for creating new work, Lulu Mlangeni has opted out of some of her Arts Fest obligations (Delwyn Verasamy)

As a result of Covid-19 restrictions on gatherings and what this would have meant for creating new work, Lulu Mlangeni has opted out of some of her Arts Fest obligations (Delwyn Verasamy)

A winner of the second season of So You Think You Can Dance in 2010 and the winner of the Sophie Mgcina Best Emerging Voice Award for 2015, Mlangeni is convinced that her breakthroughs manifest in intervals of five years. Her joie de vivre — inextricably tied to her artistic persona — is tempered with introspection more than sadness when she thinks about how the momentum of 2020 was scuppered.

As a result of Covid-19 restrictions on gatherings and what this would have meant for creating new work, she has opted out of some of her Arts Fest obligations, which would have included an 11-episode online series about the development of Kganya, culminating with a live-streamed performance as the quartet.

“I met with the creative team and posed the idea to them,” Mlangeni says. “They loved it, but that is as far as I went with it. Most of the things I create I explore in the space with the people involved.” Like many artists at this time, she describes her equilibrium and will to create as being “on and off … Sometimes I’d be inspired by what’s happening; sometimes I’d feel depressed. It was different every day. At some stage I was thinking about my career. ‘Is this the right choice that I’ve made here?’ But ja, this is what I love. This is me. This is my life.”

Although the loss of income and the unsuccessful attempts at compensation have ramped up existential angst in the arts community, coming to grips with new modes of production has compounded these issues. For Mlangeni, it’s something she’d rather take a rest from, choosing instead to focus on a documentary being produced for the festival.

Although her financial blues have been cushioned by being able to dip into some savings, Mlangeni is, similarly to Nyamza, concerned by what she sees as dancers being relegated to the bottom of the totem pole in the seemingly hierarchical dispensing of funds by the department of sports arts and culture. “I feel like policy is what we need to protect our rights to work and income and have the means to know our value as performers,” she says.

Towards the end of March, Sports, Arts and Culture Minister Nathi Mthethwa released a statement saying that R150-million was set aside to offer relief to practitioners in the sector, who could apply for the relief from April 2 to 6.

By the time applications closed, the department had received nearly 5000 entries from artists. Of the successful applications, only 1320 had been sent for payment by the end of May, with only 592 artists receiving a once-off payment, capped at R20 000, by then. This was later extended. “The balance is being attended to every day,” Mthethwa was quoted as saying.

In the written responses, Ndlovu said, “It is important to note that these figures are changing by the minute and we have been briefing the public and will continue to do so. The department has been occasionally releasing the figures and will continue to do so until the process is complete. Furthermore, the minister will release the facts and figures to the public once the last application has been processed and completed. As of 10 June, 759 payments had been processed and to date, 854 relief fund applications have been processed for payment. 180 appellants have been paid and all 32 legends have received funding.”

After hearing about the call to apply for relief, Phatsoki was discouraged when she “got word of the number of people who were applying and compared it to the funds”.

Phatsoki is the resident DJ to sought-after artist Sho Madjozi and co-founder of the bi-monthly incubator for queer and femme DJs, Pussy Party. “This time of the year is usually festival season across the world. My work plans at home, Hong Kong, Paris [and] Berlin, to name a few, were all postponed or cancelled.”

Phatsoki say all work plans have been postponed or cancelled. (Delwyn Verasamy)

Phatsoki say all work plans have been postponed or cancelled. (Delwyn Verasamy)Nomuzi Mabena, a rapper and television host who also works as a master of ceremonies for live events, is one of the artists who applied for relief. When the first 21 days of the lockdown were announced, Mabena had to cancel 12 shows from her calendar. The longer the lockdown persists, the more events Mabena has had being cancelled or rescheduled indefinitely. Unfortunately, her application was denied because she didn’t have contractual proof of bookings to back up the alleged event cancellations.

She didn’t possess the proof because bookings are often informal. “It’s just like, “Yo Muz, Sunday. Rockets, R15k. Are you in?” We often don’t have contracts in place and we’re learning the hard way” says Mabena.

Before she received feedback from the department, Mabena wasn’t holding her breath in anticipation receiving relief. “It’s not because they don’t care about us. There just isn’t a relationship between us as artists and the department. We don’t fully understand what the other one does or can do,” Mabena says.

In the meantime, the bulk of Mabena’s lockdown income is coming from producing social media content (performances, reviews and hosting Zoom conferences) for the likes of Red Bull and Castle Lite. “I’m grateful to have what they call a bankable brand that allows me to collaborate until I can go out there and earn a living the way I normally would.”

Public-relations strategist and project co-ordinator Kgauhelo Dube, who lost a six-month book-tour project because of the pandemic, says, “What I’ve seen in this time since the lockdown is that Europe and the [United Kingdom] understand the developmental processes of creative work and have made accessing relief funding administratively easier for their own people, whereas here there’s great emphasis on performers whose gigs were cancelled vs arts practitioners like myself who do the heavy lifting before the showcase.”

Dube has since decided to find collaborators and partners outside South Africa who understand the importance of keeping the early stages of the artistic value chain going within the confines of our global restrictions.

“This economically stressful downtime has presented us practitioners, administrators, producers and strategists with time to connect and work towards isolating key problems that continuously keep black artists in ‘struggling artist’ mode.

“The great challenge for black artists is trying to straddle bread-and-butter issues with building [the] industry — that compromises us and we end up not having energy for sustainable industry development,” Dube says. “Having said that, ideology will be key — we need to learn from those who came before us; they were unapologetic about their ideology within their artists’ collectives.”

Ndlovu said the department did the best it could under severe Covid-19 regulations. “Of course, we are aware of the challenges that came with some of the facilities being closed during Level 5 and 4, but judging by the number of applications the department received, a significant number of people would manage to apply. However, we opened another channel for appeals and most artists who appealed have been approved.” She said the White Paper, endorsed by Parliament in February, would help quicken the pace of transformation in the industry across sectors.