The world makes your body, 2020 (Gerhard Marx / Goodman Gallery)

From a distance at first — possibly from the other side of the room. Then up close, very close, so that you can see the lines and fragments of text emerge before you. Finally, from afar again, stepping backward slowly and watching the borders dissolve, the landscapes losing their sharp edges as the space between you and the artwork grows. You don’t have to view the works in Gerhard Marx’s latest exhibition this way, but it does help.

Titled Near Distant, this is Marx’s fifth solo show at The Goodman, his most recent being the 2019 exhibition Ecstatic Archive, also at the Johannesburg branch of the gallery, and also dealing with (among other things) the complexities of the South African landscape. In Near Distant, one of the central motifs for this body of work is that of distance. For Marx, distance can be many things — loss, longing, uncertainty, and more. The challenge, he says, “is to engage distance without it turning into nearness”.

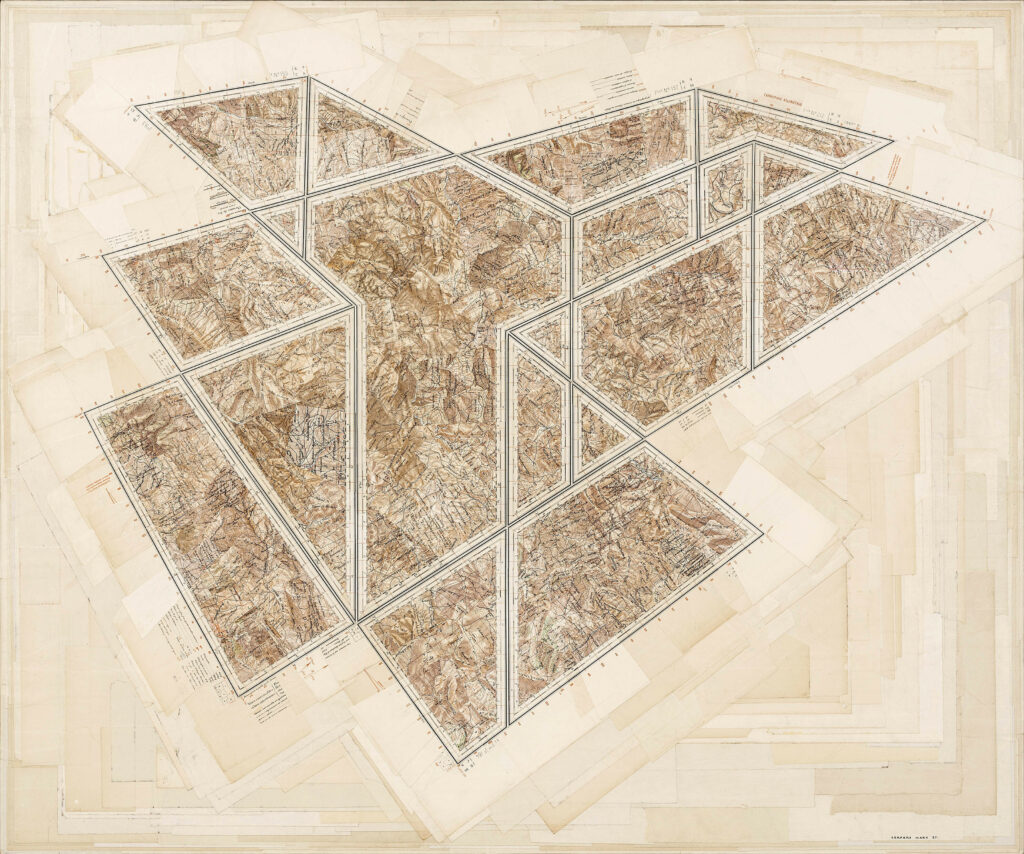

A Slant Light, 2019. (Gerhard Marx / Goodman Gallery)

A Slant Light, 2019. (Gerhard Marx / Goodman Gallery)

This approach shows up in various forms throughout the exhibition. The works require a certain amount of space — room to unfold and expand before you — but there is also a level of detail to each that pulls you in, always. This detail is sometimes incidental, other times deliberate. Marx’s use of the seemingly concrete components and vernaculars of cartography, such as the solid lines signifying roads, highways, railways and more, frequently call for a closer look, urging viewers to follow these composite lines and trace the shapes that form there.

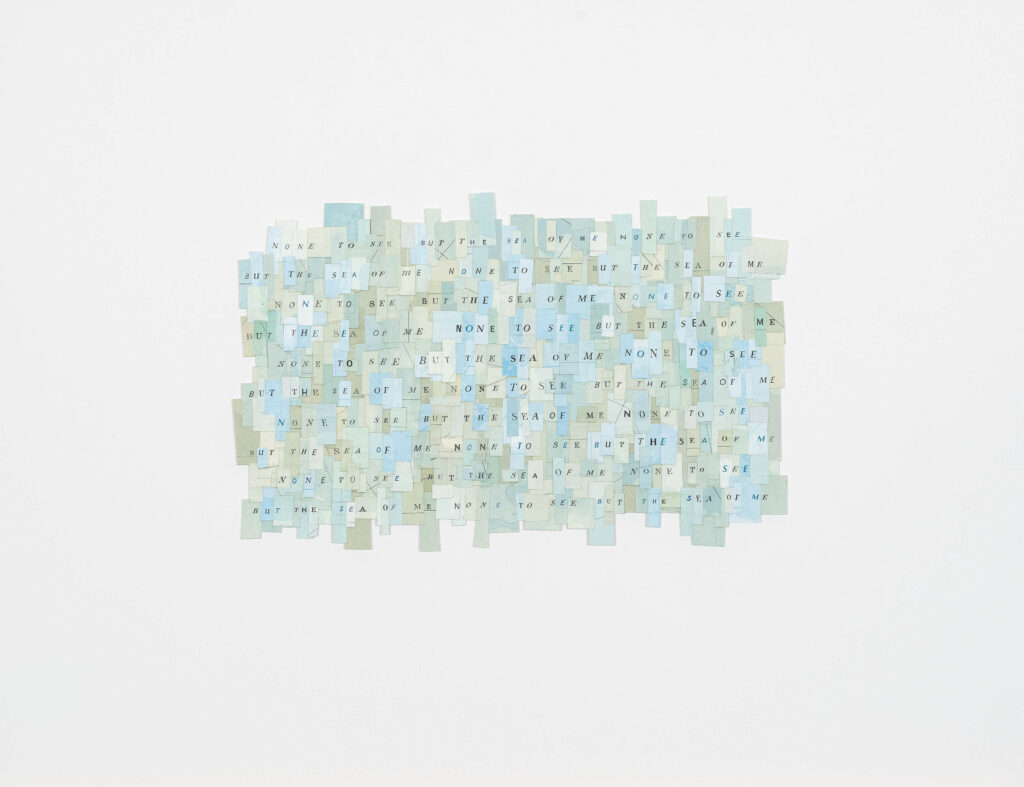

None To See, 2020. (Gerhard Marx / Goodman Gallery)

None To See, 2020. (Gerhard Marx / Goodman Gallery)

In A Slant Light a patch of bureaucratic red is ensconced by deep, watery blue and rigid, black lines, while The Same Place, Excavated Twice anchors thin, white and black margins into the rich browns of the landscape. Both works play with perspective and possibility brilliantly, and are useful primers to a body of work that frequently prizes the speculative and the provisional over the kind of enduring, practical precision we believe we’ll find in a map.

As much as borders, both literal and figurative, serve to frame and reinforce our understandings of space, distance, territory and more, it is also the quiet work of words that influence the way we move through the world. The practical, prosaic role of text in a map becomes far more lyrical in the collaged format. In many of the works in Near Distant, words are exploded and rearranged through the secondary nature of collage. Shards of haphazard text scatter across landscapes while names of towns, mountains, cities and more are chopped in two, rendering them unfit for the job of designation.

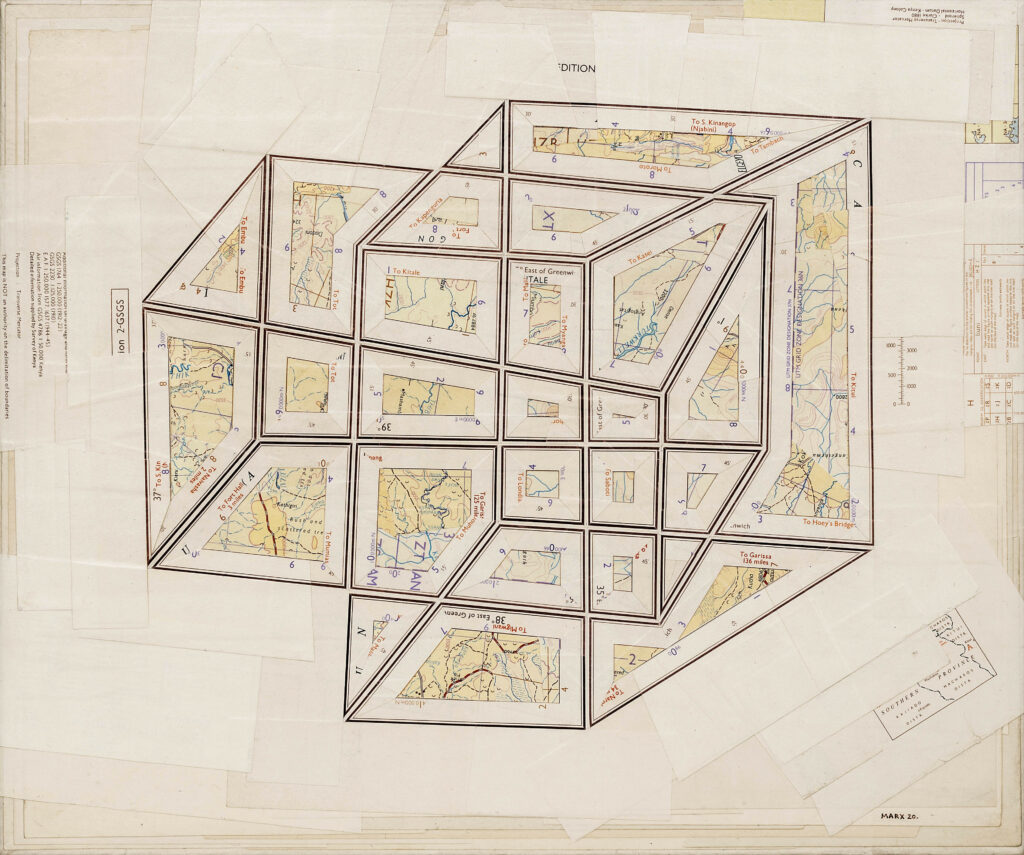

Two Things (III) , 2020 (Gerhard Marx / Goodman Gallery)

Two Things (III) , 2020 (Gerhard Marx / Goodman Gallery)

In a work like ‘Two Things (III)’ text is both instructional and playful. The work is made up of expressive geographic fragments, each one containing a thoroughly unhelpful direction running alongside an inlay of land: “To Kasei”, “To Hoey’s Bridge”, “To Garissa”. Following these directions is an exercise in futility and isolation, and ultimately makes for a map of unfinished expeditions or unfulfilled yearnings.

Two newer works by Marx make direct use of language in their composition. None to see and The world makes your body source individual letters from the artist’s archive of maps to make up their respective refrains — “None to see but the sea of me” and “The world makes your body and your body makes the world”. The two works, distinct in their composition and use of text, bring to the show a gentle consideration of individual and collective identity, and ways of being in the world. There’s also something to be said about the way that these pieces are exhibited. Both are held in display case-style wall-mounts that jut out at the bottom in a way that prompts viewers to lean over the work ever so slightly, an act of intimacy that also requires maintaining one’s distance.

In a narrative vignette included in the exhibition statement, Marx explains how, a day before South Africa’s national Covid-19 lockdown, he realised that he would lose access to stones. “While others were stockpiling at shops,” writes Marx, “I was at the quarry on De Waal Drive, overlooking Cape Town’s harbour and cityscape, collecting stone from the edges of the quarry, stockpiling stone, stockpiling touch.”

The same place, excavated twice, 2020 (Gerhard Marx / Goodman Gallery)

The same place, excavated twice, 2020 (Gerhard Marx / Goodman Gallery)

Like the other four personal texts included in the statement, this one speaks to various moments and motivations in the works on exhibition. Two sculptural pieces, however, claim a more immediate relation to Marx’s stone-searching anecdote. Near Distant (brick) and Near Distant (stone) are wonderfully playful sculptures, both made up of a series of folds, corners and flat surfaces, each section seemingly informing the gesture and direction of the next. In the presence of the rest of the works in Near Distant, these sculptures can read as fortified structures, isolated vessels, monuments to touch, or exercises in intimacy.

Like Marx’s map works, with all of their spatial imaginaries and improbable perspectives, these sculptural works are in constant dialogue with themselves and with their viewers, always prompting new ways of seeing and engaging with a landscape we’ve allowed ourselves to think of as being rational, exact, and unchanging. As we continue to make sense of shifting levels of absence, presence, intimacy, loss and more in a post-pandemic world, refiguring the role of distance in our daily lives, in the shifting physical and psychological landscapes we traverse, can be a good place to start.

Near Distant runs at the Goodman Gallery Johannesburg until September 8.