Patrice Lumumba is transported in a Congolese army truck through Léopoldville, now known as Kinshasa, after his arrest. An officer holds the rope that ties his wrists. (Bettmann Archive)

At long last, Patrice Lumumba’s remains, a tooth or teeth taken away to Belgium as a trophy after his murder on 17 January 1961, will be returned to and buried in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The homecoming follows a Belgian court ruling.

In an interview with the German broadcaster Deutsche Welle, the daughter of the slain Congolese leader, Juliana Lumumba, said, “My first reaction is, of course, that this is a great victory because at last, 60 years after his death, the mortal remains of my father, who died for his country and its independence and for the dignity of black people, will return to the land of his ancestors.”

The two front teeth were taken away by Belgian police officer Gérard Soete, then based in what is now known as the DRC, who was involved in the grim, almost ritualistic disposal of the deposed Congolese prime minister’s body and that of his associates. On the night of 17 January 1961, Lumumba; the former vice-president of the senate, Joseph Okito; and Maurice Mpolo, a minister of youth and sports in Lumumba’s cabinet, were taken from prison and driven away to be executed by firing squad in a forest outside Elizabethville (now Lubumbashi).

Lumumba had been deposed in a coup instigated by the West the United States’ CIA, working together with the Belgians, in September 1960. In his place the Congolese army chief of staff, Joseph-Désirée Mobutu (later Mobutu Sese Seko) was installed, inaugurating a brutal and kleptocratic reign, which lasted until 1997.

The next night, January 18, the Soete brothers — Gérard and Michael — returned, together with their Congolese assistants, and exhumed the bodies. The colonists didn’t want the graves to be a shrine. On the night of January 21, fortified by whisky, Gérard, Michael and their assistants set to work, chopping the body limb by limb and dissolving it in sulphuric acid supplied by the Belgian mining giant Union Minière. What remained after the ritual were bones, which they burnt and scattered about, and a tooth, or two front teeth — Lumumba’s. (It appears that Gérard took two front teeth, although the ruling by the court refers only to a tooth.)

The man who disposed of Patrice Lumumba’s body, Gérard Soete, wrote a book about his gruesome act (Photo: Cilo/Gamma-Rapho)

The man who disposed of Patrice Lumumba’s body, Gérard Soete, wrote a book about his gruesome act (Photo: Cilo/Gamma-Rapho)

The ceremonial dismemberment of the bodies is symbolic of the fate of the DRC itself. In terms of resources — people, good soils, plentiful rain, forests and minerals including gold, coltan, copper, cobalt, diamonds and uranium (it was Congolese uranium in the bombs that dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending World War II) — it is one of the richest countries on Earth, but with nothing to show for it.

“There are those who believe he will come back from the dead,” Soete said in a 1999 interview at his home in Bruges. In the way he mutilated Lumumba’s body, Soete seemed also to be in the fearful grip of the millenarian myth of the eventual return of the slain leader. “Well, if he does return from the dead,” gesturing to the two front teeth, “he will have to come back without these. He had very good teeth. They even had gold plating at the back.” Soete found an odd, morbid glee in the deaths, and even later wrote a book about his involvement in the assassination, The Arena: The Story of Lumumba’s Assassination.

Soete’s pleasure in the murder continued right to his death, when he bequeathed the tooth (or two teeth) to his daughter. In 2016, Ludo de Witte, the sociologist and author of the tome The Assassination of Lumumba, sued the daughter to give up the tooth, which she surrendered to Belgian justice authorities.

Toppling the leader

On attainment of independence, on 30 June 1960, Lumumba told his audience, including the Belgian king, Baudouin, “No Congolese will ever forget that independence was won in struggle, a persevering and inspired struggle carried on from day to day, a struggle, in which we were undaunted by privation or suffering and stinted neither strength nor blood. It was filled with tears, fire and blood. We are deeply proud of our struggle, because it was just and noble and indispensable in putting an end to the humiliating bondage forced upon us.”

Such boldness is what Malcolm X was referring to when he said that Lumumba was “the greatest black man who ever walked the African continent. He didn’t fear anybody. He had those people so scared they had to kill him. They couldn’t buy him, they couldn’t frighten him, they couldn’t reach him. Why, he told the king of Belgium, ‘Man, you may let us free, you may have given us our independence, but we can never forget these scars.’

“The greatest speech — you should take that speech and tack it up over your door. This is what Lumumba said: ‘You aren’t giving us anything. Why, can you take back these scars that you put on our bodies? Can you give us back the limbs that you cut off while you were here?’”

By setting himself up as radically opposed to the exploitation of his country, which had begun with the Atlantic and Indian Ocean slave trades, and continued with the brutal period when the Belgian king, Leopold II, personally owned the Congo, Lumumba set his administration against the West from its inception.

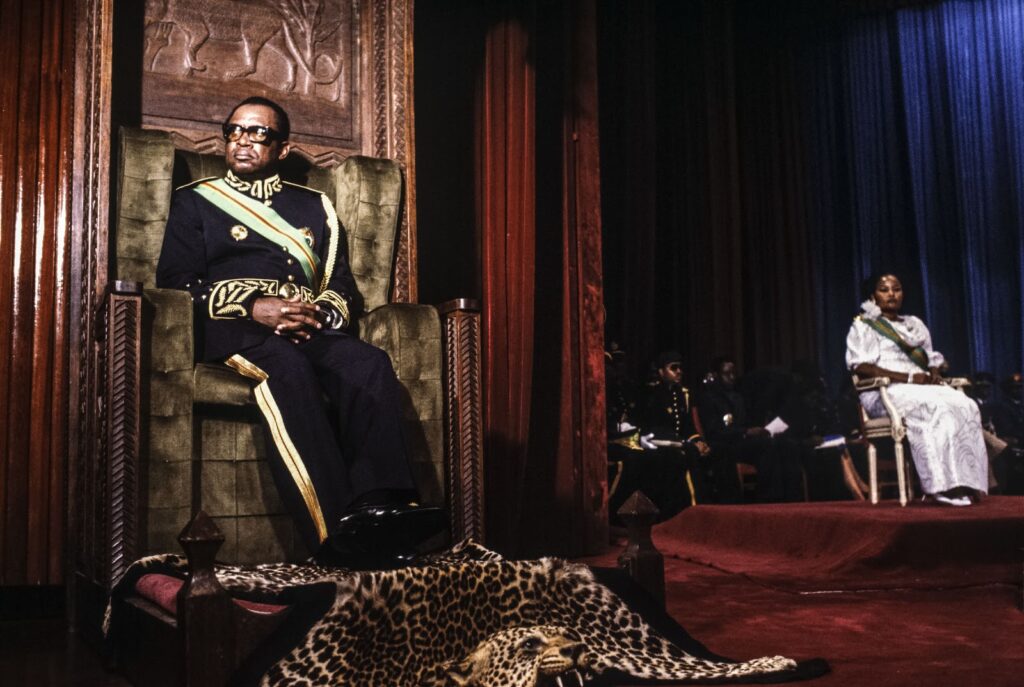

Le président zaïrois Mobutu Sese Seko lors de la prestation de son serment constitutionnel avec son épouse Bobi Ladawa Mobutu le 5 décembre 1984 à Kinshasa, Zaïre. (Photo by CILO/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Le président zaïrois Mobutu Sese Seko lors de la prestation de son serment constitutionnel avec son épouse Bobi Ladawa Mobutu le 5 décembre 1984 à Kinshasa, Zaïre. (Photo by CILO/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Within days of his becoming prime minister, there was a mutiny in the army, labour strikes, looting and ethnic clashes, even an attempt on Lumumba’s life. The mineral-rich province of Katanga, whose capital was Elisabethville, seceded to form a breakaway state with Moïse Tshombe as its leader. In a radio broadcast on July 11 1960, Tshombe said the new state would be independent, but would maintain an economic bond with Belgium.

When Lumumba appealed for support from the United Nations, then headed by its Swedish secretary general Dag Hammarskjöld, to restore order, he got none, forcing him to turn to the Soviet Union. By the end of September 1960, the Congolese leader had been toppled, and a replacement found. He was arrested and, a few months later, he and his comrades were taken from the Elisabethville prison they were held in, shot and killed.

Laying to rest

The return of the tooth or teeth follows a plaintive letter in June by Juliana Lumumba to the king of Belgium for the return of the remains. “The years pass, and our father remains a dead man without a funeral oration; a corpse without bones,” she wrote. “In our culture, like in yours, respect for the human person extends beyond physical death, through the care that is devoted to the bodies of the deceased and the importance attached to funeral ritual, the final farewell. But why, after his terrible murder, have Lumumba’s remains been condemned to remain a soul forever wandering, without a grave to shelter his eternal rest?

“In our culture, like in yours, what we respect through care for the mortal remains is the human person itself. What we recognise is the value of human civilisation itself. So why, year after year, is Patrice Emery Lumumba condemned to remain a dead man without a burial, with the date January 17 1961 as his only tombstone?”

In some cultures, like the Shona, to resolve the incompleteness of a death without a funeral liturgy — to bring the wandering, restless spirit to repose — they bury an animal, which stands in as an avatar for the deceased. In a ceremony known by some as chimombe mumbwa and by others as kuunza, a goat is ritually slaughtered, its head covered in a cloth, and it is buried as if it were a human being.

With the return of the tooth or teeth, there is a modicum of release, but Lumumba’s struggle, for the people of the DRC to control their resources and determine their own destiny, still continues, even though Sese Seko has been dead for more than two decades. Sese Seko fled into exile when the Lumumbaist nationalist, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, the leader of a coalition of Congolese rebels backed by Ugandan and Rwandan rebels, overran the national army and became the DRC’s president in May 1997. Kabila, perhaps not coincidentally, was himself assassinated on January 16 2000 — just a day before the 40th anniversary of the death of Lumumba.

Parselelo Kantai’s piece, “Julius Kambarage Nyerere”, in the Chimurenga edition Who Killed Kabila was valuable reading for the grim details of the deaths of Lumumba and his associates.

This article was first published by New Frame.