Nono Motlhoki’s Lenyalo questions generational burdens of culture on women.

(Courtesy of Veefatso Motlhoki)

Towards the end of June, Stevenson Gallery and the Visual Arts Network of South Africa (Vansa) invited artists to submit their portfolios for review with the opportunity to develop and refine their work through robust dialogue with the gallery’s team. Executed through virtual studio visits and conversations, this set of portfolio reviews gave form to The Nonrepresentational.

The exhibition spotlights an impressive collection of work by 12 artists working in various mediums. Participating artists include: Lebogang Mogul Mabusela, Heinrich Minnie, Nonkululeko Dube, Boitumelo Motau, Londiwe Mtshali, Nico Athene, Valerie Asiimwe Amani, Celimpilo Mazibuko, Tshepiso Mabula, Nono Motlhoki, Callan Grecia and Io Makandal.

The strength of the exhibition is that it functions outside a singular and uniform organising principle. Instead, artists included traverse divergent and complex personal, ideological and political questions.

Mabula and Mtshali explore history and memory through intimate portraits of everyday rituals. Amani, Motlhoki and Athene centre the body, pointing to the complexities of identity through performative gestures. Makandal and Minnie offer up investigations of the urban landscape through symbolism and abstraction. Motau explores mythology and religion through depictions of human-like creatures. Grecia, Mazibuko and Dube’s works are reflections of the post-apartheid condition through symbolism, text and the human figure. Mabusela uses tradition and feminist theory, disrupting the workings of patriarchy through the creation of handmade paper guns.

The exhibition draws on the meanings of the term “nonrepresentational”, which, in art criticism, is parallel to “abstract”.

Londiwe Mtshali’s Izithunzi traces rituals. (Courtesy of Londiwe Mtshali)

Londiwe Mtshali’s Izithunzi traces rituals. (Courtesy of Londiwe Mtshali)

As a double entendre, the term also points to the fact that artists are not represented by the gallery. Typically, representation means an artist will be incorporated into the gallery’s programme with structural institutional support. This allows the artist opportunities to exhibit and sell works. Representation is a meeting of the minds between the two parties.

The Nonrepresentational exhibition was held virtually, through the gallery’s online viewing room. Curated by two staff members, Lemeeze Davids and Dineo Diphofa, it offered a rare moment where “junior” team members flex, champion projects and receive recognition for their work. The term “junior” is in quotation marks because tenure is not always correlated to the level of meaningful contribution one brings to a team. To paraphrase artist and scholar Hito Steyerl, we all know that the art world survives on the commitment of hardworking women and stressed-out interns.

An interesting aspect of the exhibition is its potential to function as an alternative to the long-established artist-gallery relationship formulated on the basis of representation. Interestingly, the term “nonrepresentational” carries specific meaning in the realm of human geography. Associate professor of human geography at the University of Plymouth, Paul Simpson, describes the nonrepresentational [theory] as a diverse body of work that highlights alternative approaches to the conception, practice and production of knowledge where the nonrepresentational reorients [geographical] analysis beyond an overemphasis on representations.

Valerie Asiimwe Amani’s All the English You Ate reflects on the complexities of identity. (Courtesy of Valerie Asiimwe Amani)

Valerie Asiimwe Amani’s All the English You Ate reflects on the complexities of identity. (Courtesy of Valerie Asiimwe Amani)

Although the theory is conceived in an entirely different field, I find this language and analysis useful in relation to process — the notion of drawing on alternative approaches that reorient relationships beyond an overemphasis on representation. Here, the reorientation prioritises the activity of artmaking (and its commerce) over technical (perhaps even legal) constraints. One has to consider whether critical and sustained engagement outside of representation could result in a more natural and swift flow of knowledge, expertise and capital.

A decade ago, an initiative such as this one might have been about visibility, where a possible positive outcome for the artist would be increased visibility. Perhaps this is less so since the escalation of social media apps (particularly Instagram) as productive sites for marketing and sales. Many artists, including those in this exhibition, continue to find ways to use social media to garner interest and productive engagement regarding their work. But building a sustainable practice is not just a “number of followers” game, it is also about access to different kinds of audiences — collectors, institutions, academics, curators, writers and supporters, many of whom can be reached through the gallery system.

As we work together to build a post-pandemic new normal, something that is constantly on my mind is how we are thinking through questions of access, equity and equality. I question the extent to which programmes are inventive in expanding modes of working

and offering new ways for artists to gain access to institutional structures.

It was disappointing to note that all 12 artists in the exhibition are either studying or have studied at the Wits School of Art, Michaelis School of Fine Art, The Market Photo Workshop, Durban University of Technology, the university currently known as Rhodes and the University of Oxford.

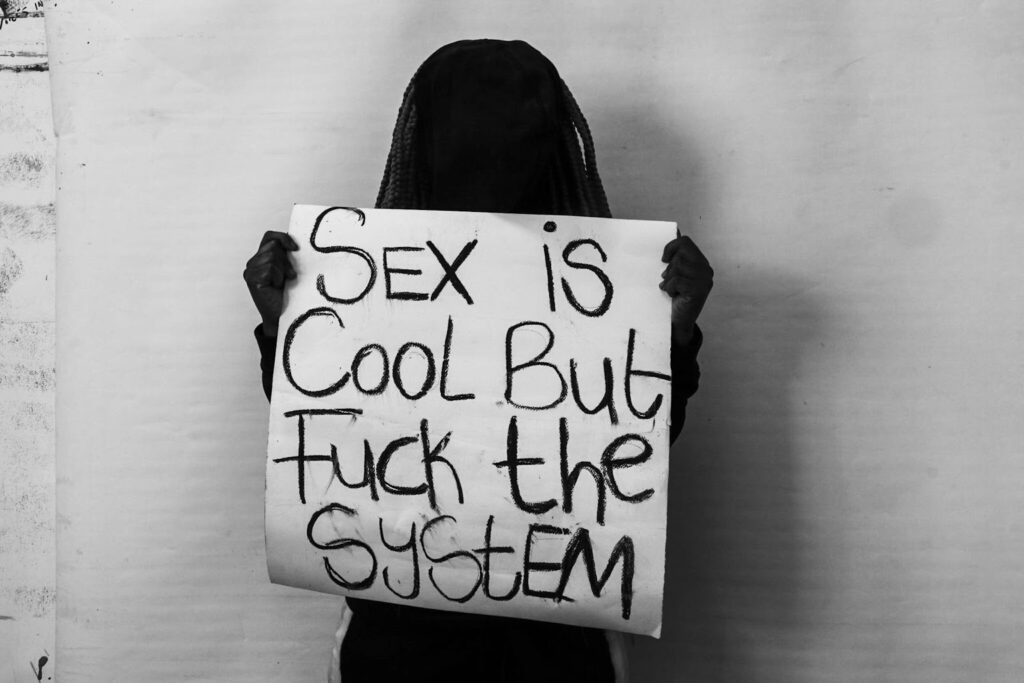

Nonkululeko Dube’s Fuck the System comments on post-apartheid South Africa (Courtesy of Nonkululeko Dube)

Nonkululeko Dube’s Fuck the System comments on post-apartheid South Africa (Courtesy of Nonkululeko Dube)

Most have also been included in exhibitions at galleries and institutions in various parts of the country. These outcomes might be a product of a few things, one of which is the initial demographics in Vansa network as well as the demographics of applicants. The centring of formal education is concerning, especially in a country where the struggle for free and decolonial education continues.

Upward mobility and access can’t be so closely tied to formal education because this contributes to inequality and uneven cultural representation. As I am advocating for more “diverse inclusion” I’m also aware of the fact that artists operate under very different value systems where access, success and flourishing careers can be defined by a different set of parameters. This is what one hopes for — the creation of hybrid spaces of working and relating that do not conform to the mainstream and the recognition of different systems, which will provoke and inspire change.

Like many online exhibitions, The Nonrepresentational expands traditional practices of display beyond physical spaces, however, it does so without departing too much from the curatorial processes of critical reflection, investigation and discovery. I’m not fully convinced of the extent to which the exhibition — or, more appropriately, the project — offers a vastly different model to how artists and galleries to work together.

The exhibition can be viewed at stevenson.info.

This article was produced as part of a partnership between the Mail & Guardian and the Goethe-Institut focusing on innovation in various aspects.