War is the backdrop of The Shadow King, by Maaza Mengiste, which has been shortlisted for the Booker. (Photo: Nina Subin)

“She can hear the dead growing louder: We must be heard. We must be remembered. We must be known. We will not rest until we have been mourned. She opens the box.”

These lines are taken from the first few pages of Maaza Mengiste’s second novel, The Shadow King. But as much as they describe the emotions of Hirut, the protagonist, they echo the authorial project itself; as Hirut braces herself to remember the dead of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, it is also Mengiste’s work to resurrect them.

“For me, it was symbolic of the way that we all have a responsibility to reclaim our dead, to remember them and speak of them in such a way that we understand the kind of future that they were working towards; that they were fighting for,” Mengiste tells me during our Zoom interview. “So that moment with Hirut opening that box felt to me — it was momentous for her.

“But it’s also, for me, just that act of excavation of history. You know, that act of looking in archives: it’s very often opening those boxes and seeing what emerges [and] steps out; what should I be paying attention to?”

In The Shadow King, it is the women warriors who Mengiste pays attention to, writing them into life from the margins of history. As well as acknowledging their roles in the “official” business of war — soldiers killing each other on battlefields — she also explores the effects of that war that has no ceasefire: the war against women’s bodies.

When Hirut, who has evolved into a formidable soldier, kills a man for the first time, she is not thinking of the Italian enemy before her; instead, in her mind she sees Kidane, a commander on “her own side”, the man who raped her.

“She has practised it so many times … during training, and in her sleep, and as she dreamt, that her body knows just what to do. She imagines Kidane and pulls the trigger.”

To capture the historical details of the war, Mengiste conducted extensive archival research. But to create the characters’ lived experiences, she had to turn inwards.

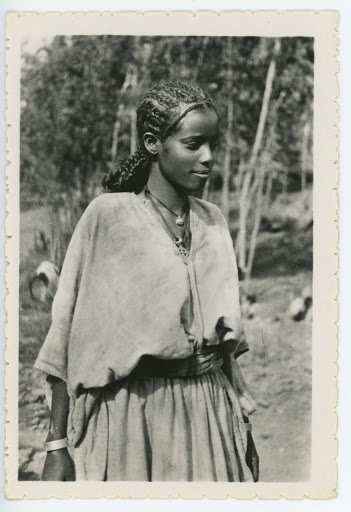

‘I came across this picture of a young girl who fitted the mental image I had of Hirut in The Shadow King,’ Mengiste writes. (Supplied by Project 3541)

‘I came across this picture of a young girl who fitted the mental image I had of Hirut in The Shadow King,’ Mengiste writes. (Supplied by Project 3541)

“Writing scenes of sexual assault — writing scenes of fear; of deep, paralysing hopelessness — I think it’s something that many of us can relate to and, you know, certain elements of our lives,” she says. “And I had to draw on that to render these scenes. That was really hard.”

These scenes are not easy to read either, but redemption is offered in the quality of the prose, as was Mengiste’s intention. “What I wanted to do in those difficult moments, was to create language; to write in such a way that it gave me as a writer, a mercy — a way to float above this, even if I’m looking down and creating it. And I wanted to give that same thing to the reader as well: find a way that language could blunt that pain.”

Mengiste credits Toni Morrison, particularly the novel Song of Solomon, for inspiring this approach. “I was taking lessons from the way that she used language to convey violence, but also to offer us a shelter in that language.”

The decision to use fiction as the lens through which to illuminate Ethiopian history was also how Mengiste approached her first novel, Beneath the Lion’s Gaze, set during the Ethiopian Revolution in the 1970s. During her first semester as a graduate student in the New York University MFA programme, Mengiste says she really grappled with “the enormity of history; with the national tragedy [of the revolution]”.

“Hundreds of thousands of people died, and I wasn’t sure how to convey this through fiction,” she says.

When Mengiste spoke to her professor (none other than Breyten Breytenbach) about this dilemma, he said: “You know, you must write this as fiction. Because fiction tells a truth that history cannot.”

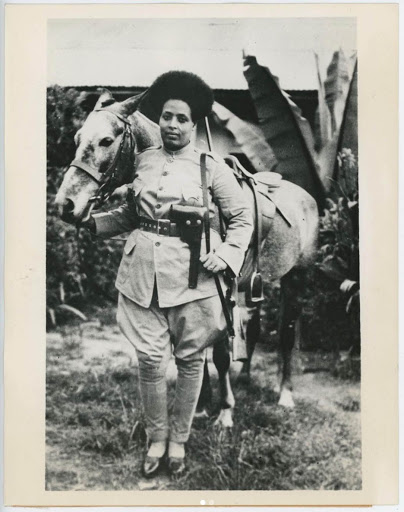

Archival material such as this 1935 image of a woman soldier inform narrative and structural elements of the novel. (Supplied by Project 3541)

Archival material such as this 1935 image of a woman soldier inform narrative and structural elements of the novel. (Supplied by Project 3541) “I held on to that, because it was powerful,” Mengiste says. “It was a powerful reminder of the power of literature, and the power of novels, to render something that history has never quite been able to do, which is to tell you how something felt as it was happening — not just what happened. And I wanted to do that part: I wanted to tell what it felt like for people who had often been ignored by history.”

The Shadow King is written in the present tense. As well as capturing an immediacy that affords the reader emotional resonance, for Mengiste, her choice of tense is also a comment on the nature of history, and the mechanics of remembrance.

“I was thinking about the way that memory works, and the way that even when we are sitting in a specific moment in time, we remember things, and we feel them as if they’re happening now.

“You know, nothing is truly past; nothing has ever really gone — not those memories that have been the most impactful,” she says.

“I can be sitting here on November the ninth, and on a Monday, and I can think about something in Ethiopia in 1975. And it’s happening right now — in my head, in my memory — and I can feel something again. I wanted to write the book in present tense because I wanted to write history as something that never leaves us; we drag it forward with us. I wanted to convey that through just a switch of the tenses: that nothing is past.”

One of the kinks of historical novels is the interplay between the past that is being written about and the present in which the narrative is actually being written. Many of the themes in The Shadow King seem very much of our current moment: the reclamation of women’s stories and agency, and the encroaching authoritarianism around the globe (and the fight back against this), among them.

But Mengiste cautions me against too easy a reading: “I started writing this novel in 2010/2011. Way before the Me Too movement; way before the rise of authoritarianism in the United States or anywhere. I was writing this unaware that we would have a Black Lives Matter movement. I was writing what history was making apparent to me, which is something that wasn’t dictated by current movements.”

It is not about using contemporary concerns to shed a new light on history. Rather, as Mengiste puts it, “We are now catching up with the past.”

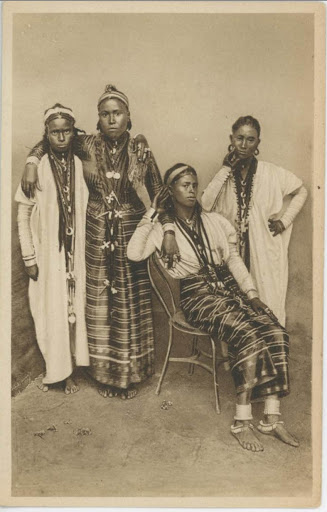

‘This photograph kept me company as I developed the women and girls who would join the army or resist the fascists in their own ways,’ says Mengiste (Supplied by Project 3541)

‘This photograph kept me company as I developed the women and girls who would join the army or resist the fascists in their own ways,’ says Mengiste (Supplied by Project 3541)

The Shadow King is one of six novels shortlisted for the 2020 Booker prize, with the winner due to be announced on 19 November. I realise, hours after our interview, that I have neglected to ask Mengiste about what this means to her. But it’s a matter of seconds to find her enthusing about the recognition online. “It is unbelievable. I cannot tell you. It felt like some part of my world exploded open; that things were possible,” she told the BBC.

Whoever is declared the Booker winner, The Shadow King is already finding its way into the world beyond its pages. It’s been optioned by Atlas Entertainment, and is in the early stages of development, with Kasi Lemmons writing the screenplay.

There’s also Project 3541, a photographic archive of the 1935-41 Italo-Ethiopian War. Mengiste used photographs extensively in conducting her research, and descriptions of these images inform both narrative and structural elements of The Shadow King.

“Even before I was really thinking of writing my first book, I was fascinated by these photographs that were taken of this time period in Ethiopia. I don’t know why, but little by little, I would collect them,” she says.

“I realised, ‘Oh my gosh, these photographs might actually help me with my research, you know; that this is a story I wanted to write.’ They were a visual narrative of this history that I was interested in. And I needed to look at them as much as I looked at written documentation to understand what was actually happening in that war.”

Project 3541 is an ongoing enterprise, with photographs available both on the website and on Instagram at @theshadowkingnovel.

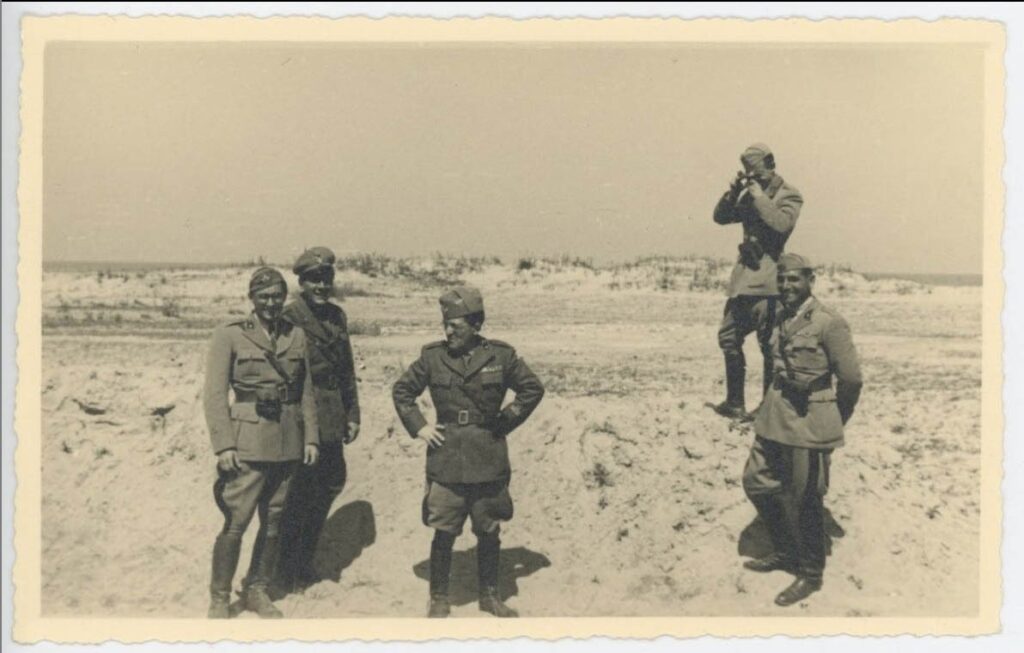

‘Soldiers brought their cameras to war when Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935. Photography was another weapon of war. It would glorify the quest for an Italian empire in Africa.’ (Supplied by Project 3541)

‘Soldiers brought their cameras to war when Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935. Photography was another weapon of war. It would glorify the quest for an Italian empire in Africa.’ (Supplied by Project 3541)

“I am asking everyone to be in contact with me to share their stories of family members who had anything to do with this conflict. I’m hearing from people in England; I’m hearing from people in Italy; I’m hearing from people in Eritrea. And in Ethiopia, for sure. You know, there were prisoner-of-war camps in South Africa that took Italian soldiers.”

Mengiste emphasises that the Second Italo-Ethiopian War involved more than just the two countries that lend it their names.

“This was something global,” she says. “And I want this history to be known on those terms: that there were many different groups of people involved. This is really an act of reclamation. It is a way to establish this history that happened in East Africa as world history, because it involved the world.”

We’ve mostly spent our time discussing past wars, but the prospect of civil war in Ethiopia looms over our conversation. As shown in the pages of her novels, Mengiste’s focus is always on the human cost.

“It’s distressing to think of Ethiopia possibly going into a civil war. I can’t help thinking about the civilians who will inevitably be involved in this,” she says. “War is not a neatly packaged enterprise,” she says. “You know, the point of it is to destroy: it’s about destruction.”

We end with a quotation from The Shadow King, one that encapsulates both futility and fledgling hope in a time of war, whether domestic or on a bigger stage: “There is no choice but forward … There is no way out but through it … There is no escape but what you make from the inside.”

This article was produced as part of a partnership between the Mail & Guardian and the Goethe-Institut focusing on various aspects of innovation