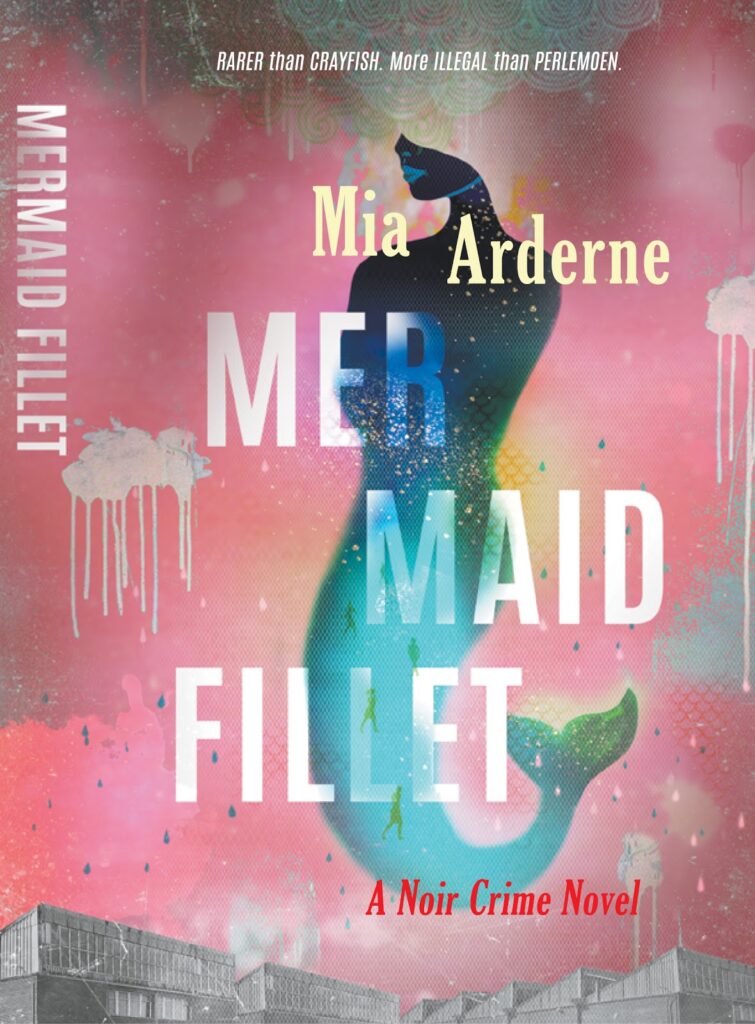

Mia Arderne says she was not quite prepared for the emotional investment that went into writing her debut novel Mermaid Fillet. (Supplied)

Writer Mia Arderne’s debut novel Mermaid Fillet (Kwela Books) emerges shattered and kind of pieces itself together from there. The work of an obsessive diary keeper, the book gathers fragments from the author’s fleeting thoughts and formative years, exploding context and repurposing trauma. It shimmers with beautiful lines and confidently relegates plot to the sidelines.

Set in a pseudo-gangster world which involves the smuggling of mermaid tails, the book centres the inner worlds of intersecting, archetypal characters, animating them with a sensibility that draws from new media, popular culture and a delicate consideration of positionality.

Arderne, a short story writer and magazine columnist, comes ready to play with text. Although the book exhibits an immediate charisma, its underside cannot be shooed away. In an interview, Arderne says it was the emotional investment of writing the book that she wasn’t quite prepared for. Pulling from the past and her personal life as much as she does, she admits that “several parts of the novel were triggering to rework”.

In this interview, she speaks about form, the tightrope of stereotypes and some of her formative writing experiences.

‘I was just trying to explore these characters that I found quite interesting, but then it became about exploring this underworld mermaid empire,’ says the author. (Kwela Books)

‘I was just trying to explore these characters that I found quite interesting, but then it became about exploring this underworld mermaid empire,’ says the author. (Kwela Books)

Your book is set within the realm of gangsterism but it is also tongue in cheek, with a lot of tangential stories and over-the-top characters that come into view. What book did you set out to write?

The book is about illegally smorkelling mermaids in Cape Town. I don’t know whether I intended it to be that when I started writing it. I was just trying to explore these characters that I found quite interesting, but then it became about exploring this underworld mermaid empire.

The way I did it was more organic than formulaic, exploring elements of magic realism within this underworld of smuggling mermaid tails. I didn’t know what the ending was going to be while writing it. Certain things happened quite organically, like menstrual bloodstorms, expanding love bites, characters’ mouths and legs being spliced together from depression.

Those kinds of elements happened as I explored the characters and the world they existed in. I suppose I explored hyperreality in a way that was personal to me, but I didn’t really intend for the premise to be what it is now.

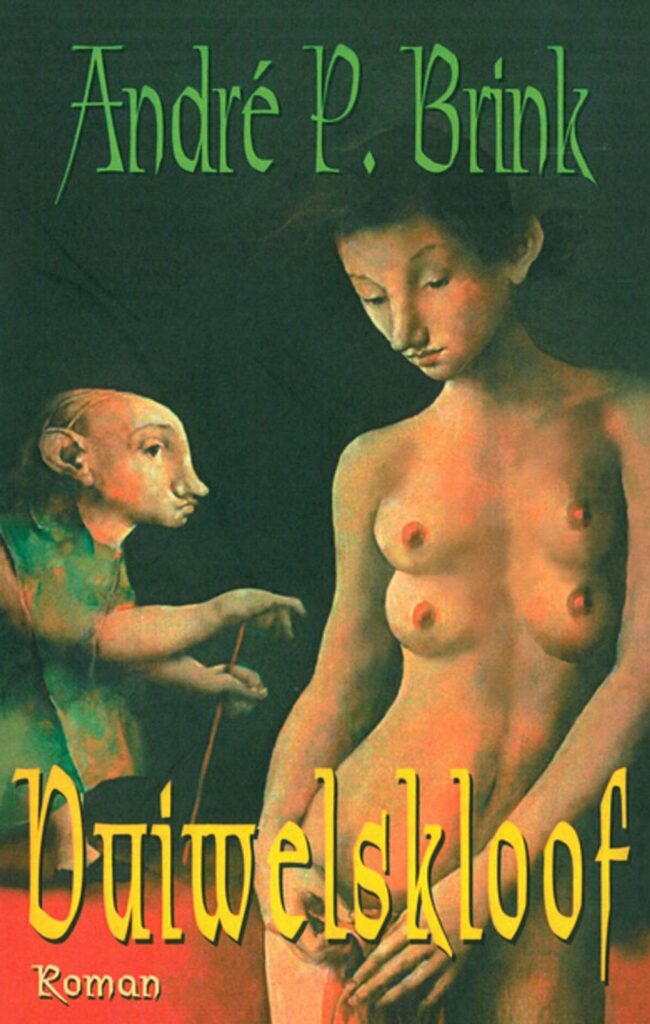

In the list of influences you put together for us, you mentioned André Brink’s Duiwelskloof as foundational. Pulp Fiction and Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club are seminal, too. What is it about the imagery here that resonated with you?

In high school, I loved André Brink and Duiwelskloof. The book itself is steeped in magic realism. It’s wild. There is a kind [child] there with four boobs. It’s just really beautifully written. That was one of the first longer novels that I got into. It had a massive impact on me. So did the works of Quentin Tarantino, and Guy Ritchie films. They are largely male and very violent influences, but that is what my adolescence was largely marked by and so the work kind of appealed to me. It does show through, because the book is exceptionally violent and there is a lot of toxic masculinity in there, so it mirrors that a little bit.

‘That was one of the first longer novels I got into. It had a massive impact on me,’ says Arderne

‘That was one of the first longer novels I got into. It had a massive impact on me,’ says Arderne

There is a line there where the character Isaac thinks: ‘Nothing is lonelier than a relationship.’ The way you write sex, it feels like people are fucking for dear life; beyond lust, beyond passion. How did you work towards a language that captures this?

I’m still very skaam about my sex scenes. I struggle to even look at them and I can’t believe that I’ve had people related to me even reading them. They are incredibly graphic and they go beyond the sexual. The tief Letitia is fucking to forget. She just wants to be choked out and feel like she is going to die. So it becomes a commentary on how she is needing to leave this realm of consciousness.

With Isaac and his boyfriend, they fuck like it’s penetrating the loneliness, but it isn’t. You can fuck like you are getting past that loneliness even though it’s just fucking. So it becomes something different for all of my characters.

AK, who is this genuine ou, like a family man, a topi; he is a devoted husband but he is low key into BDSM. It all comes across as really gentle and loving, but there is something more insidious going on there, as well, particularly for Letitia, who likes to feel like she is gonna die.

A line between that being a kink and a moving towards more and more suicidal thinking is played on, a little bit, with that dynamic. So the sex manifests where the characters are psychologically.

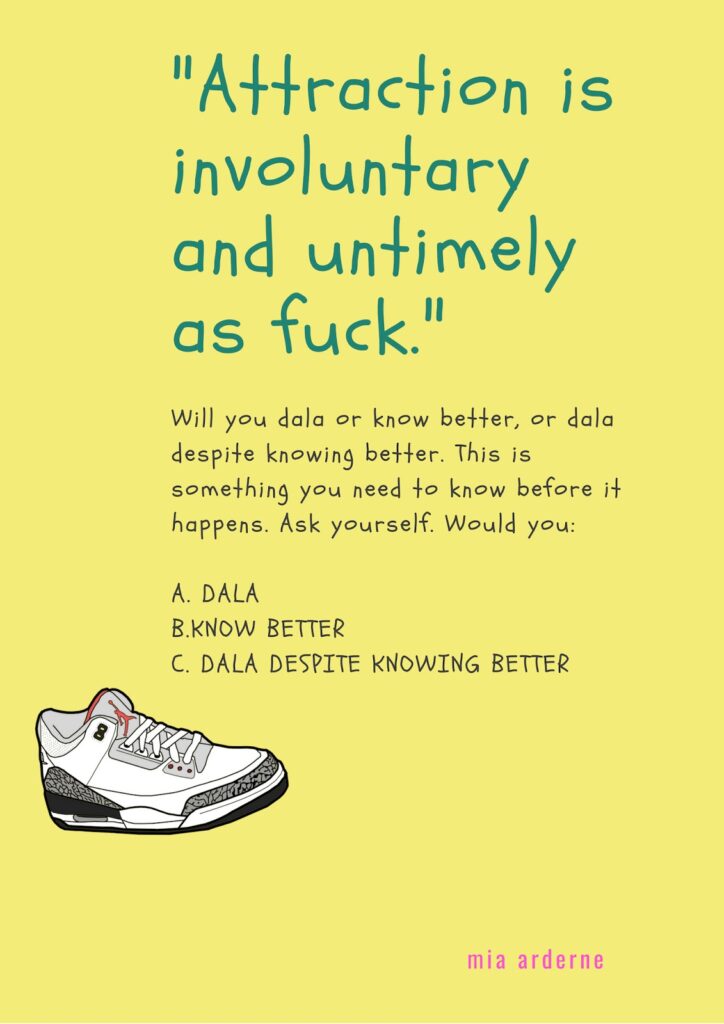

For Mermaid Fillet, Arderne designed these character cards. ‘They kind of helped me to solidify the characters during the writing process,’ she says.

For Mermaid Fillet, Arderne designed these character cards. ‘They kind of helped me to solidify the characters during the writing process,’ she says.

How gangsterism is portrayed — especially in South Africa, even through movies set, say, in Cape Town — realism is usually the conduit. Transgressing into another form of depicting that world, how worried were you about maintaining your integrity, how the work could be perceived, how it still could play into stereotypes? Even within a potentially liberating form, it still feels like a tightrope you are walking.

It was difficult to navigate because my characters are archetypes. There’s a maalnaai, a tief; they all kind of represent people we know. My characters are largely wannabe gangsters; I wouldn’t call them real gangsters because it’s not a real gangster world. I don’t think there is any other way I could have written it.

Many stories coming out of the coloured context go in that direction of almost documentary-style realism. I was initially encouraged to go in that direction, but I just didn’t want to. I don’t see the reason for literature within the lived experience that I have to always be in a kind of poverty porn style. Things can be very surreal and very violent and draw on that kind of world at the same time.

I wouldn’t be able to write a real Cape Flats gangster story because that isn’t my lived experience. I think it’s important to stay in your lane. With magic realism I was able to create my own style and my own world around it.

‘I’d drawn images for all the characters, and then it was my editor’s idea to release them as Pokemon cards. It was to help people get a feel for them without reading the book.’

‘I’d drawn images for all the characters, and then it was my editor’s idea to release them as Pokemon cards. It was to help people get a feel for them without reading the book.’

In what other forms has the book existed in terms of style and presentation. You mentioned that it has been a long time coming?

Some of the oldest passages go back with me to when I was at school. There were passages I wrote when I was very young about some darker experiences I kept with me, before I had a laptop. I reworked them. There was a manuscript that got shortlisted for the Dinaane Debut Fiction Award, but it didn’t win. Some passages are taken from that as well, that I reworked and adapted into some of the characters in Mermaid Fillet. Some of it I wrote when I was burning in my feelings very gesuip … It comes over a period of many years.

You deal with mental illness in a raw but sensitive way.

I think that was the easiest to do. I suffer from mental illness. The characters … It was just true to them. The tief with PTSD from childhood trauma: the trauma is pivotal to who she becomes. It plays out throughout her life; it just makes sense to call it what it is.

The grootman is a suicidal kingpin with severe depression, who doesn’t trust joy. That’s immediately relatable to me. You feel happy and you immediately don’t trust that happiness. You struggle to reach for the kettle and when you do, you’re like, “fuck, this joy is fleeting, it’s gonna end. The world is going to become ugly again.”

It’s easier to write about that shit if it is what you go through. Social anxiety, as well, with the sturvy kind. It’s dismissed because of her access and privilege. Those ways of being were organic to the characters. All I really did there was call those mental illnesses what they were.

One of the mock up covers for Mermaid Fillet (Kwela Books)

One of the mock up covers for Mermaid Fillet (Kwela Books)

After such a landmark work, what’s next for you?

I’m not sure of a lot of things yet. At the moment I’m working on a script called How to Stop Being a Naai, which is like a self-help guide to being not a naai. I’m kind of writing that for myself, I’m not sure yet whether I will share it or publish it. Other than that, I’m thinking of pitching columns again. The game has changed since Covid, so I’m not sure if any of those things will get accepted.