‘This was when the mask was brand spanking new. Before it got rusted from drinking all the brew.’ This image and caption were posted on DOOM’s Instagram on 30 October 2020, a day before he passed. (MF DOOM/ Instagram)

In high school, our saving grace from weekends of boredom and long weeks away from home was a friend’s three-hour-long VHS tape of videos from Yo! MTV Raps. KMD’s single, Peachfuzz, would be my introduction to group member Zev Love X, an early character of Daniel Dumile. Most famously known by his prolific alter ego MF DOOM, Dumile passed away on 31 October 2020, with his death only being announced on 31 December, two months after.

Peachfuzz was a vibraphonic, puppy-love anthem that featured the group’s boisterous, alliterative flows. Its cute chorus made it my friend’s favourite jam on the tape. Thinking back on it now, his bias might have had to do with the fact that Zev had already built what might have easily been the golden era’s most beguiling flow: a dense, nimble thing capable of sounding playful while embodying laments about the evils of the world.

“Now use your imagination, just a smidgen/ If I was a bird I’d be a pigeon/ Succumb one to crumbs and pizza crust, when every fella can/ Eat fresh fish and live fat like a pelican,” he rapped on the song.

Of course, it was the boyish tones of the brothers Subroc and Zev Love X that enabled Peachfuzz to be passed off as a song about “rapping to girls”. On closer inspection, it unravelled the precariousness of black manhood, from its infantilisation by “the man”, to how it was hemmed in by consumerism and hypermasculinity — heavy subjects to compress for teenagers whose voices had yet to break.

Although KMD showed promise and erudition, their hold on the public imagination would prove slippery when, in 1993, Subroc was hit by a car while crossing the freeway in Long Island.

KMD’s Black Bastards, shelved around the time of its scheduled release, would eventually hit the streets in 2001 on Sub Verse Music

KMD’s Black Bastards, shelved around the time of its scheduled release, would eventually hit the streets in 2001 on Sub Verse Music

Around the same period, the release of Black Bastards, the group’s follow-up to their debut LP Mr Hood, was sabotaged by Elektra Records after its cover of a Sambo character being taken to the gallows was deemed controversial. Following these double blows, Dumile slipped from public view for a few years before regaining the mettle to make music again.

When he emerged with his face concealed, eventually settling on a Gladiator-esque mask, it was under the name MF DOOM, a character based on his name but also on the Marvel comics villain Victor von Doom. He had vowed, it seemed, that his creative output would be strictly on his terms, this time.

The transition, although years in gestation, was not seamless. Measured against others in what could be considered a DOOM trilogy, Operation Doomsday sounds the rawest, like MF DOOM is still coming into being, peeling off the layer of Zev Love X to reveal the fragile new casing of a different character.

Zev, a jovial although quite obviously militant fellow, is, in some ways, not fully exorcised here. You hear it in how the new alter ego careens past the contours of his own rough-hewn beats with almost juvenile abandon.

In the overall outlook, there is more vengeance and irreverence than there is mystery and strategy.

A critical success and a standout in a vast catalog, Operation Doomsday marks Daniel Dumile’s debut as MF DOOM

A critical success and a standout in a vast catalog, Operation Doomsday marks Daniel Dumile’s debut as MF DOOM

The unstoppable creative force inhabited by DOOM during this period is confirmed by DJ Stretch Armstrong, among a nucleus of people who witnessed this rebirth. “DOOM recorded most of that over a three-week period in my apartment on my MPC, using my records,” tweeted Stretch in February 2019.

“He never slept for more than three to four hours at a time.” The album was initially released in 1999 on Bobbito Garcia’s Fondle ’Em Records. Its critical acclaim would open up many creative and commercial avenues for Dumile.

As if pre-empted years before by the artist, there is a clear trajectory of gruffness to DOOM’s voice stretching from Operation Doomsday (1999) to Born Like This (2009), the last album under the DOOM moniker, which bookends an incredible, decade-long run under this guise.

Often, when we listen to the work of an emcee, beyond the other elements of flow like cadence and inflection, it is the subtlety of pitch and the texture of voice that convey believability. The effect of this progressive graveling of Dumile’s voice is that DOOM becomes more credible as a subversive character with each instalment.

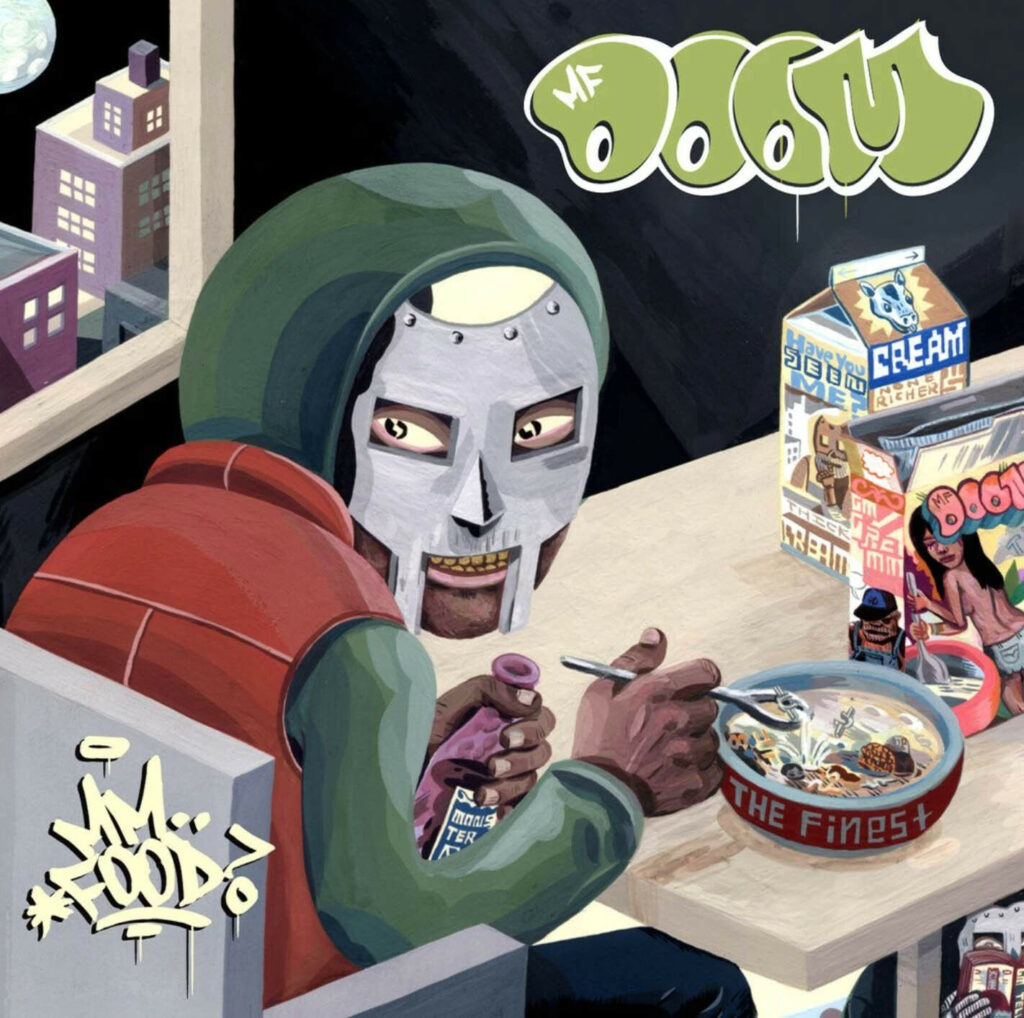

As a result, it is in 2004 (five years removed from Operation Doomsday), with the release of the astounding Mm.. Food album, that one gets the sense of the complete emergence of MF DOOM.

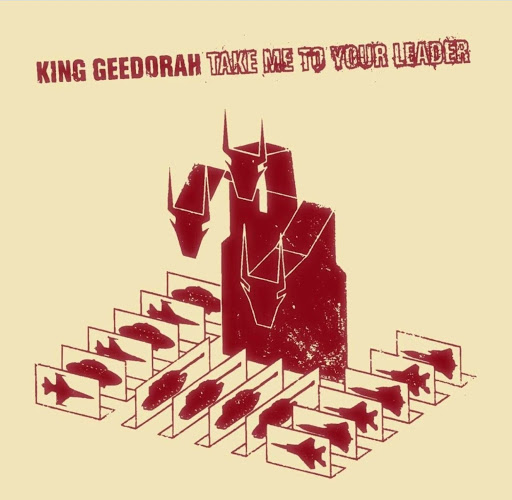

Perhaps this inkling is enhanced by the fact that Dumile had just returned from exploring other characters; most notably a three-headed reptile named King Geedorah in the ensemble album Take Me To Your Leader; and an unhinged, younger rival to MF DOOM named Viktor Vaughn, expressed in the twin releases Vaudeville Villain and Venomous Villain.

Take Me To Your Leader, more of a production showcase, seems Dumile explore a reptilian, three-headed character

Take Me To Your Leader, more of a production showcase, seems Dumile explore a reptilian, three-headed character

DOOM’s gust of activity around this period was mostly due to the fact that he had settled in a relatively quiet section of Atlanta around the turn of the century, allowing him to work unhindered by the stress of big city life. All his work made around this point seems to be neatly executed.

There is less street-level pugnacity in Mm.. Food and more of a sense of DOOM as a calculating and wisened reprobate.

A generally more deliberate delivery seems to hint at this, together with a healthy, growing disgust for the antics of his mainstream contemporaries. “Yuck, is they rhymers or stripping males, out of work jerks since they shut down Chippendales,” he grumbles on the album opener, Beef Rap.

His sound pieces, a major part of his arsenal, also seem refined, anchoring and splitting this food-themed album right down the middle.

Mm… Food is a balanced display of DOOM’s production, sound collaging and rhyming skills.

Mm… Food is a balanced display of DOOM’s production, sound collaging and rhyming skills.

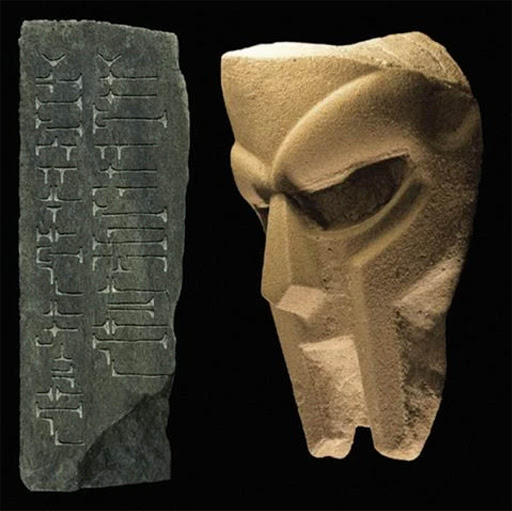

People usually lose their minds over Madvillainy, the Madlib collaboration that preceded Mm… Food by a matter of months, whereas 2009’s Born Like This often doesn’t get its due. And yet it’s a superb suite, if only for what it tells us about the closing of the DOOM chapter as a solo endeavour.

On this album, there seems to be a tangible sense of recognition that this may be his swansong as the lonesome villain, although he would go on to collaborate fruitfully with several producers and artists throughout the next decade.

There is the immediately unyielding ferocity displayed on cuts like Gazzillion Ear, in which DOOM rhymes like he is putting on a rapping exhibition, tossing off stitched up Dilla beats like they are 45s warped by his lyrical heat.

There is the monumental Absolutely, the finest retributive justice anthem in that hallowed tradition set off by Body Count’s Cop Killer. Here, ever so significantly, DOOM begins by clearing his throat, as if expelling years of pent up repugnance.

Born Like This, DOOM’s last solo outing under that name, is an intense display of his rap skills.

Born Like This, DOOM’s last solo outing under that name, is an intense display of his rap skills.

He assumes the voice of a ringleader, instructing his army on a long-term MO: “Our species is in danger/ Wear gloves and strike in a city where you a stranger/ That’ll let them fools know/ And send them a message, let them POWs go”

Over a brooding, understated Madlib soundscape, we collectively fantasise about a righteous “red flood” to descend on “the piglets”, decreed by the villain with a soft heart.

In That’s That, DOOM rhymes as he does in Rhymes Like Dimes, like he is doing it for sport, except the humour is pegged to a ferocity. The rasp is ground down to a growl, and the rhymes are packed tighter than bunions in secret socks — just in case this is your first and last encounter.

While the clandestine one sometimes scaled back on his flow, and used texture and subtle inflections as our mothership through his dark, contradictory world, “don’t ever forget that it always boils down to beats and rhymes”, is the apparent lesson in this song.

It is living proof that, in the fashion of Guru and Premier, the formulas were always being updated with every turn at bat. In this way, Dumile taught us all to be artists.

For many in South Africa, the passing of Dumile was the last bit of news we took in in 2020. In an Instagram post on the MF DOOM account by his partner, we found out, incredulously — but then again maybe not — that Dumile had “transitioned” two months before, on 31 October.

Given the attention to detail with which he inhabited his many guises, in particular that of DOOM, you could perhaps forgive us for thinking he would come back smirking at us from behind the wheel of a yacht in the Caribbean.

For in life, and in art, Dumile has cheated death and despair many a time. Most inspiringly, in a treacherous, corporatised world, he achieved his noble goal of speaking exclusively through his art.

By sticking to his guns and maintaining a safe distance from behind his metallic shield, he gave us a panoramic view of the machinations of power, arming us with information on how to live and, ultimately, how to die.