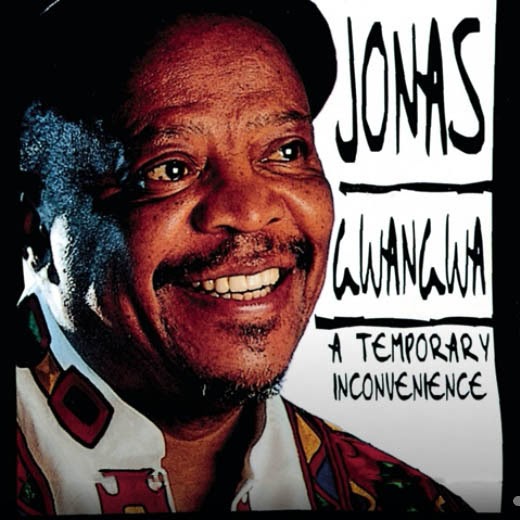

Jonas Gwangwa during a march to the Southern African Music Rights Organisation. (Ruth Motau)

As young reporters at the Sunday Times back in the ’90s we were assigned to interview prominent South Africans for the paper’s Christmas edition. One of the people on my list was the legendary musician, composer and cultural activist Dr Jonas Gwangwa. To say I was intimidated by the name would be an understatement.

I dialed the number and someone, a young woman, answered the phone. She asked me to hold on. After a few moments a man greeted me in a firm, rather intimidating voice from the end of the line.

“Hello?”

“Hello sir, is that Mr Gwangwa?”

“Yes, who is this?”

“Sir, this is Lucas Ledwaba from the Sunday Times …”

“Ledwaba?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Likuphi?” he inquired, switching to our mother tongue SiNdebele sase Nyakatho [Northern Ndebele].

Gwangwa sounded surprised that I actually spoke the language, and did so with proficiency. This helped to break the ice and we spent more than an hour on the phone — even though all I needed from him was a short Christmas message to South Africans. It was clear he loved his language and was, like many MaNdebele elders, on a mission to ensure it never died.

I was left spellbound a few years later and shouted in absolute joy when I heard for the first time, a mainstream artist, none other than Gwangwa, singing in my mother tongue. Unless like me, your mother tongue falls in that category of tongues known as minority languages, you may not understand why something like this, which for many people is normal, meant so much.

My mother tongue, Northern Ndebele is spoken largely in Limpopo, parts of northern Mpumalanga, North West and northern Gauteng. Northern Ndebele falls under the tekela group of Nguni languages. These include SiSwati, isiHlubi, isiBhaca and sePhuti. It should not be confused with isiNdebele which is spoken on Ikwekwezi FM and is among the country’s 11 official languages.

isiNdebele, spoken by the renowned visual artist Dr Esther Mahlangu, together with the isiNdebele spoken in Zimbabwe, fall under the zunda language group of the Nguni, which includes isiZulu and isiXhosa. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco), if nothing is done, half of the more than 6 000-plus languages spoken worldwide today will disappear by the end of this century.

With the disappearance of unwritten and undocumented languages, says Unesco, humanity will lose not only an irreplaceable cultural heritage, but also valuable ancestral knowledge embedded, in particular, in indigenous languages.

Through its endangered languages programme, Unesco supports communities, experts and governments to help to preserve indigenous languages. Unesco has declared the decade 2022-2032 as the “decade of indigenous languages”, which is meant to recognise the importance of indigenous languages to social cohesion and inclusion, cultural rights, health and justice. It also highlights indigenous languages’ relevance to sustainable development and the preservation of biodiversity, because they maintain ancient and traditional knowledge that binds humanity with nature.

There are 10 South African languages in the Unesco Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. These are all Khoi and San languages that are either highly endangered or extinct. Programmes such as this one by Unesco are important, but it is the people themselves who are key role players in the preservation of indigenous languages.

For instance, my late parents may not have known about Unesco or its programmes. But today I’m grateful to them for the greatest heritage gift of all: instilling the love, knowledge and appreciation of our mother tongue, as well as teaching us to take pride in it.

We must have been one of only a few families in Soshanguve township, where I grew up in the 1980s, who spoke the language daily, openly and, I must add, with pride. There was this unwritten rule that in our home, this was to be the only spoken language.

Even in public spaces — at football matches or supermarkets — this is the language we spoke among ourselves, much to the delight and surprise of those around us. Yet we knew well not to speak any other language at home, especially in the presence of our stern father, who would not hesitate to call to order anyone violating this golden language code. “Munrwana wami [my child],” he would say if he overheard you speaking another language. “Nga bani nngale [whose house is this]?”

Of course, you would sheepishly respond that this is the house of Ledwaba, to which he would then demand to know why a foreign language was being spoken in this house of Ndebeles. At school we studied Northern Sotho, because there was no school that offered the language in the entire country. We were even told there was no Northern Ndebele book in existence.

‘It was with much shock and absolute disbelief when one day back in 2000 while driving in Johannesburg, I heard Jonas Gwangwa using a SiNdebele phrase on his album A Temporary Inconvenience (Epic/Sony Records 2000).’

‘It was with much shock and absolute disbelief when one day back in 2000 while driving in Johannesburg, I heard Jonas Gwangwa using a SiNdebele phrase on his album A Temporary Inconvenience (Epic/Sony Records 2000).’

Our teachers, just like our friends and neighbours, always made good-spirited fun of us and our language. But it wasn’t anything malicious. They too seemed fascinated by our language and envied the fact we actually spoke this unknown tongue.

I remember one day when a man walking past our house overheard us speaking and stopped in his tracks in total surprise and a reasonable amount of shock. We were making sandals from cardboard boxes and the man appeared absolutely fascinated by the SiNdebele word for shoes, “tikrabula”. He asked us to repeat the word quite a number of times while he listened in fascination. In the end, he struggled to pronounce it and walked away.

In the streets, my friends made good-spirited fun of some of the words we used, like “sidudu”, which means “pap”. The only other time we heard other people speak SiNdebele was at family gatherings or if we visited our kin in the then northern Transvaal (now Limpopo). In those days, hearing someone speak or sing in the language on radio was just a dream. I don’t even think it is something we ever imagined possible.

So, it was with much shock and absolute disbelief when one day back in 2000 while driving in Johannesburg, I heard Jonas Gwangwa using a SiNdebele phrase on his album A Temporary Inconvenience (Epic/Sony Records 2000).

Gwangwa, whose ancestral roots are in the heartland of the MaNdebele GaMagongwa in Mashashane, Limpopo, is also of Ndebele origin. He grew up in Orlando East in Soweto.

But for some reason I had not expected him to sing in SiNdebele. After all, he is an internationally decorated and respected musical genius who lived in the United States and Europe for many years. So, when I heard him remark, “liNdebele la sumela mala li yafa” in his song Shebeen Queen, I had to pinch myself. It felt unbelievable. Gwangwa continued this trend in the 2001 album Sounds From Exile, where he opens the song Afrika Lefatshe la Badimo, which is sung in Sepedi, with a popular SiNdebele medley.

In the 2008 album, Kukude, he sings an entire song, Lituba Lami (My pigeon), a SiNdebele folk song, entirely in the language. It goes like this:

“lituba lami li tegwe gubani?

ndilibonile lihleti esihlahleni

line makranda gamambiliiiiii …”

That a man of Gwangwa’s stature finds it important to sing in his mother tongue, a minority language not known to many and not even recognised by the government, underlines the importance of language and its connection to identity and self-respect. The thought of a language becoming extinct is just too tragic — its implications go way beyond the mere loss of the spoken word. But with giants like Gwangwa showing the way, it is unlikely SiNdebele will end up on Unesco’s dreaded endangered list.

Young artists, probably taking a cue and inspiration from the genius of Gwangwa, are making and recording music and other pieces of visual arts in the language.

Efforts to preserve the language continue. Scholar Dr Plaatjie Mahlobogoane has compiled a Northern Ndebele dictionary which is currently available online at. Community radio stations in parts of Limpopo broadcast in the language daily. All this is a sign that a language doesn’t need to be recognised by any institution, including the government, for it to be spoken and preserved. It is the people themselves who are primarily responsible for ensuring that their language does not disappear.

In the streets of the bustling bushveld town of Mokopane (Mughombane), people converse openly in the language. One bank has even written a notice in SiNdebele on its glass door. It reads, “tiawara te gu bhanka [banking hours]”. By continuing to speak their language, the people of Mokopane have made companies acknowledge their tongue and communicate with them in it.

Perhaps the best lesson on the importance of one’s mother tongue is carried in a statement made by African scholar and author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o during his 2017 lecture titled “Secure the Base, Decolonise the Mind” at the University of the Witwatersrand. He said: “If you know all the languages of the world but not your mother tongue, that is enslavement. Knowing your mother tongue and all other languages too is empowerment.”

Thobala ge nkhudjo Murungwa.

This article was initially published on mukurukurumedia.co.za