A director of over 40 films, Dick Fontaine’s subjects have included The Beatles, Sonny Rollins and Ornette Coleman. (Supplied)

Leading British documentary film director Dick Fontaine celebrates his 82nd birthday in Durban next month, where he has lived for about a year.

Fontaine introduced “the techniques of direct cinema to British television”, according to the Dick Fontaine and Pat Hartley Collection at the Harvard Film Archive. Starting as cinéma verité — “truth cinema” — in France in the late 1950s, direct cinema revitalised documentary filmmaking in the United Kingdom.

Over the past 55 or more years Fontaine has crafted his style of documentary filmmaking and has directed more than 40 films.

He is in South Africa because of his Durban-born partner, the filmmaker and former BBC journalist, Gugulethu Mseleku.

“We are working on stuff to do,” said the soft-spoken, friendly Fontaine. “It’s a great place for me to write.”

The subjects for his documentaries included established names in the arts and politics such as James Baldwin, The Beatles, Sonny Rollins, Ornette Coleman, Norman Mailer and Afrika Bambaataa.

A Cambridge humanities masters graduate, Fontaine joined Granada Television in the United Kingdom as a researcher in 1962. He would soon become one of the cofounders of its ground-breaking programme, World in Action. His academic grounding in the sciences and a desire to fight for human rights stood him in good stead.

He also worked a lot with Dan Pennebaker, one of the pioneers of direct cinema in the United States. “Most of those stories came out of New York. Pennebaker was very interested in [Norman] Mailer, too. So, he got involved.”

Fontaine, at times, found the author “quite belligerent. It was mainly to do with the booze. Eventually he stopped drinking; that disappeared a bit.”

In 1968, together with Mailer, Fontaine made Will the Real Norman Mailer Please Stand Up? It was based on the historic march in Washington on 21 October 1967, the year Martin Luther King Jr gave a speech lambasting racism and America’s invasion of Vietnam.

“He [Mailer] goes on the march and got arrested. The film is about what happened before he got arrested and put in prison. He used that arrest as a starting point to write the novel Armies of the Night, a brilliant book for which he won a Pulitzer Prize.”

Fontaine’s foray into jazz documentaries began in 1966 when he made a film about the American saxophonist, Ornette Coleman, in Paris. At the time, Coleman was recording a soundtrack for the film Who’s Crazy?

Although the Coleman film boosted his confidence, Fontaine could not clinch a deal to do a documentary on his childhood hero, the jazz whiz, American trumpeter, Miles Davis.

“I went to see Miles. I knew him already. I asked, ‘How much money do you need.’ He said, ‘10 000 dollars.’ I said, ‘I don’t have 10 000 dollars to give you, the budget is only 15. I can’t make a film for 5 000 dollars.’ ‘Tough,’ he whispered.

“You had to lean over to hear him well. We still remained friends. So I went to make a film on Sonny Rollins.”

The Fontaine-Rollins connection would last forever.

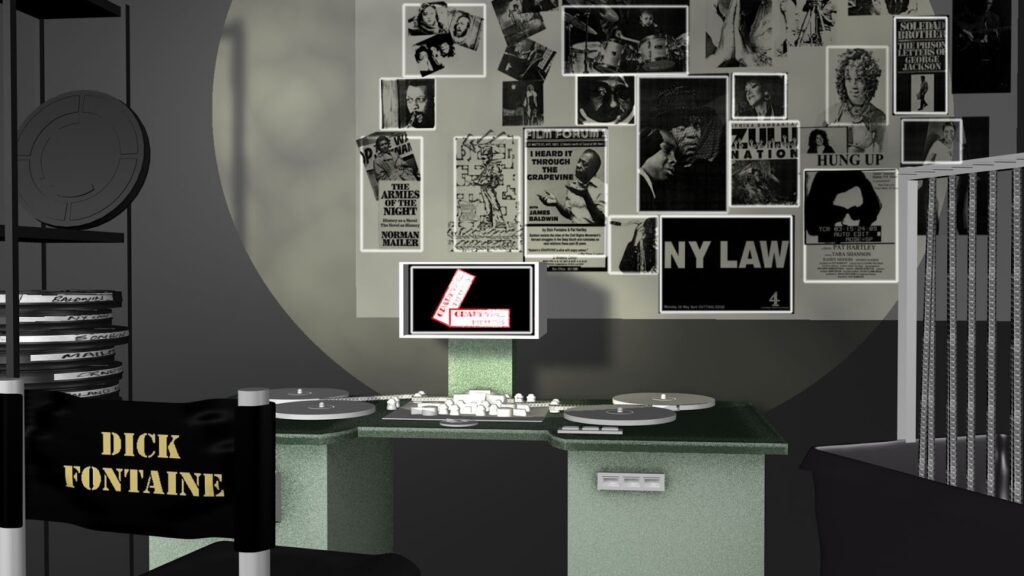

A wall depicting the artworks of some of Dick Fontaine’s films. (Supplied)

A wall depicting the artworks of some of Dick Fontaine’s films. (Supplied)

His second film on the Grammy award-winning tenor saxophonist, Rollins, titled Sonny Rollins — Beyond the Notes, was nominated for a Grierson award in 2012. It’s a sequel to his 1967 documentary, Who is Sonny Rollins?

Fontaine produced Beyond the Notes with Mseleku and British director Anthony Wall.

Beyond the Notes is pegged on Rollins’s 80th birthday on 7 September 2010. This was a hell of an event, featuring a stellar cast of jazz cats such as Roy Haynes, Courtney Pine, Roy Hargrove and Coleman, the night’s guest of honour.

In the film, influential jazz critic Stanley Crouch says Rollins epitomises the essence of jazz. “Because jazz is really about making the present work, and meeting it face to face and doing something with it. That’s what jazz is all about, summoning the power of the present.”

Doves cooing and flying over New York’s harbour is how Beyond the Notes opens. A soft Rollins saxophone tune creates an ambiance that makes one anxiously wait to see New Yorkers brave a wintry grey morning, a scene so common in many US movies. Yet, instead of throngs of people, Fontaine introduces us to a lanky and athletic Rollins in a long winter coat, walking comfortably with a friend, instrument in hand. Taken from Who is Sonny Rollins?, the opening sequence sets the scene. The main character is a man on a mission, someone who eschews recklessness and wants to do right.

Beyond the Notes reveals that the story being told began 40 years earlier. Fontaine had one burning question: “Why would a brilliant young saxophone player, who would become one of the most influential musicians in jazz, suddenly reject critical acclaim and simply disappear?”

He says in the film: “As a young filmmaker, totally in love with the sound and the spirit of the music, it seemed vital for me to try to discover why one of my heroes had quit the scene. What was he missing? What was he looking for?”

Rollins’ words in the 1967 film still ring true today. The musician says marginalisation, ill-discipline and bitterness often frustrate and ultimately destroy many talented jazz musicians. “I have seen a lot of great musicians you know… that never really had a chance to really express themselves. They were always kept to the small area of the club. And with the club, goes the whisky, you know, the degrading things, so to speak. It kills a lot of people …

“You can blow your horn and if you get great on it, you will live a good life, so to speak. And the public don’t really give a damn. So long as you sound good, they don’t care what you do. You can use drugs. You can do anything you want as long as you sound good when you get up on the stand. Well, I don’t know if it’s worth that to me.”

“Jimmy was living in France, but he would turn up and stay with his brother for the times he was in New York. That’s when we decided he was gonna go on this journey through America,” says Fontaine. (Photo: Sophie Bassouls)

“Jimmy was living in France, but he would turn up and stay with his brother for the times he was in New York. That’s when we decided he was gonna go on this journey through America,” says Fontaine. (Photo: Sophie Bassouls)

For Fontaine, a good documentary is a well-rounded picture of his or her subject. “With music, I wanted to, you know, try to get to the soul of something. The centre of it.”

Making films was not his first love. Music was. “When I realised I was never going to be a great musician, my response, was: stop trying to be one. Try to make films on great musicians instead.”

Agitated by his solidarity with the black civil rights struggle, Fontaine used his talents to help bring change. Jazz brought him closer to the black community.

“David Baldwin, James Baldwin’s brother, ran a jazz club. He was a friend of mine. His club was near where I lived in New York, down the street. I went there a lot. Also, my mother-in-law lived in the same neighbourhood — Upper West Side New York … I was there a lot. I filmed a lot in the club. Jimmy was living in France, but he would turn up and stay with his brother for the times he was in New York. That’s when we decided he was gonna go on this journey through America, retracing his steps that he had trod in the Fifties when he had met those leaders in the civil rights movement. He was gonna write something about it.”

Fontaine’s luminous 1982 retrospective James Baldwin documentary, I Heard it Through the Grapevine, was made in collaboration with his then wife, African-American actress Pat Hartley. Although the film was shot in 1980, five years before Baldwin died, it is no ghost story. This is vintage Baldwin, alive as ever, casting his big and restless eyes on the epic drama of violated black lives in capitalist and racist America.

In the film a witty Baldwin looks back with anxious rage at the turbulent history of the black civil rights movement as he searches for dear friends. He interrogates America and her bleeding political wounds. “It was 1957 when I left Paris for Little Rock, 1957. This is 1980. How many years is that? Nearly a quarter of a century. Now what has happened to all those people, the children I knew then? And what happened to this country? And what does this mean for the world? What does this mean for me? Medgar, Malcom, Martin, dead. These men were my friends, all younger than me. But there is another roll call of unknown, invisible people who did not die but whose lives were smashed on the Freedom Road.”

Does Fontaine have any films in the works?

“For the past 20 years I have been teaching young filmmakers, helping them with their work. Now I have retired from that. I probably will make another film or two. Intend to. But you know, I’m sort of easing down really.”