Saxophonist Kippie Moeketsi (left) guested on Harari’s album Rufaro/Happiness. Here, Alec Khaoli and Sipho Mabuse are seen with Pat Matshikiza and others at the recording of Tshona in 1975. (Image courtesy of the As-Shams archive)

In 1976, Afro-rock group Harari was voted South Africa’s top instrumental group. The band, comprising former schoolmates guitarist and singer Selby Ntuli, bassist Alec Khaoli, lead guitarist Monty Ndimande and drummer Sipho Mabuse, and the group — initially christened “The Beaters” — had travelled a long journey from the Soweto district of Orlando West.

Seven years earlier, the young men had been encouraged by their high-school principal to perform for school fundraisers. At that stage, they were junior disciples of what’s been dubbed the “Soweto Soul” movement: an explosion of township bands drawing on overseas rock and soul music and pre-existing South African popular music and inspired by the assertive image of Stax and Motown’s Black artists.

It was the era of rising Black Consciousness in South Africa, and the apartheid regime maintained tight control of its ethnically divided state radio stations to prevent the broadcast of “subversive” music. However, the Mozambique station Radio LM, the suitcases of travellers and record stores such as Kohinoor in central Johannesburg, allowed township music fans to stay abreast of contemporary trends.

Kohinoor, under owner Rashid Vally, became the base for first the Soultown and then the more adventurous As-Shams labels. Rubbing shoulders with their jazz peers, the young Beaters rapidly built on their Soweto Soul foundations, growing an army of equally young and increasingly rebellious fans, and cutting hit albums for the Teal label.

Journalist Derrick Thema recalled: “People were out there to support Black products [and take charge] of their self-pride and dignity. Any musician who wanted to latch on to the sentiments of Black Consciousness needed to go into soul music.” Beaters fans even had their own dance: the “monkey jive”.

During their three-month tour of then-Rhodesia, The Beaters were inspired by the independence struggle there, and a popular music scene in which indigenous sounds were being asserted. Thomas Mapfumo, and Jonah Sithole, for example, were beginning to craft their pro-independence Chimurenga music from Shona roots. On their return, the neat Nehru jackets that had been the band’s earliest stage wear were replaced by dashikis and Afro haircuts. Harari — the title and most popular track of their debut for the As-Shams label — became a band name that, in Mabuse’s words, they could better relate to “as Africans”.

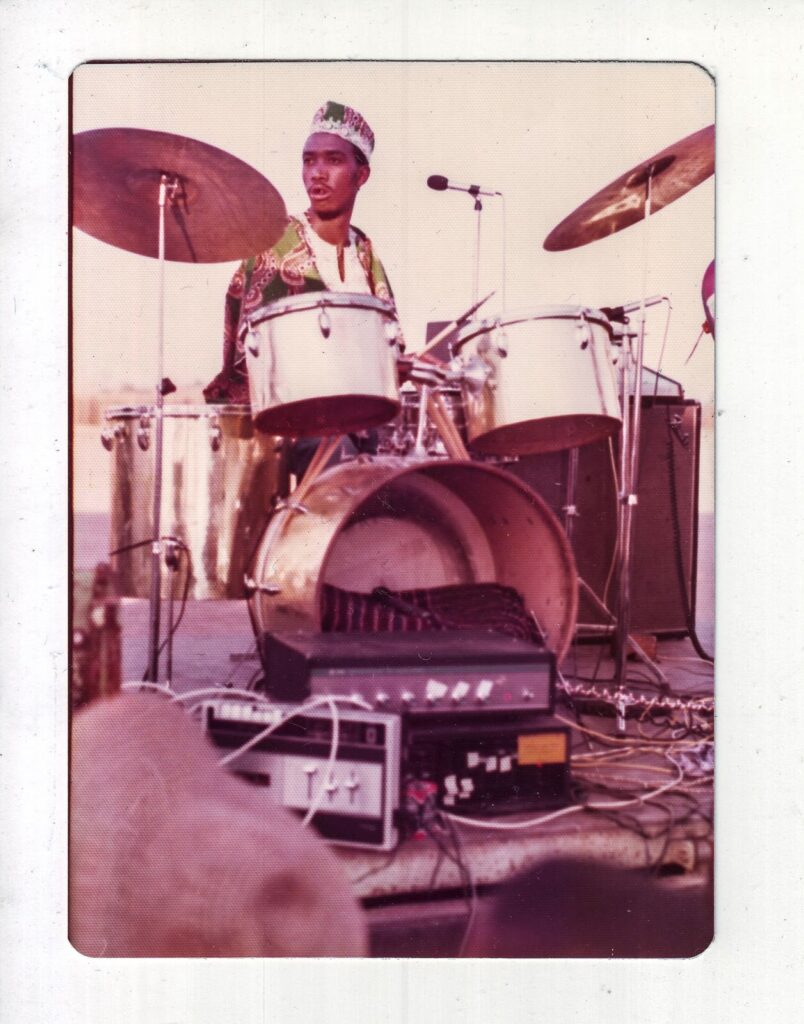

On the band’sreturn from a three-month tour of then-Rhodesia, the band’s stage wear became dashikis and Afros. Harari became a band name that, in Sipho Mabuse’s words, they could better relate to “as Africans”. (Image courtesy of the As-Shams archive)

On the band’sreturn from a three-month tour of then-Rhodesia, the band’s stage wear became dashikis and Afros. Harari became a band name that, in Sipho Mabuse’s words, they could better relate to “as Africans”. (Image courtesy of the As-Shams archive)

On 16 June 1976, the youthful rebellion against apartheid oppression burst into flames in Soweto. Unarmed schoolchildren marched against the imposition of Afrikaans as a language of instruction. Police fired on the crowd with live ammunition. Authorities admitted to 176 deaths including that of Hector Pietersen, who was only 13 years old; the true death toll was far greater. As protests spread to other cities in subsequent days, more died, and more black South Africans from all generations became involved in resistance.

“I was there,” Mabuse remembers. “It was not the kind of thing you can ever in your life forget.” His friend and Ntuli’s nephew, Khaya Mahlangu, was studying medical technology, but increasingly considering a switch to full-time music, and hanging out with Harari, with whom he later played.

On 16 June, Mahlangu “was rehearsing at the Pelican nightclub in Orlando, and somebody came in and asked us to stop: ‘There’s trouble outside’. I went home: my parents lived not far from where Hector Pietersen was shot. The township was burning, and I remember burning cars, bodies lying in the streets…later that day we were shot at while taking a cousin home …” he recalls.

In the months that followed, Harari were still working on their music and growing their following. Work opportunities became more limited, however, as curfews and restrictions were imposed. “As it got more difficult, some of the bands that had started the Soweto Soul era phased out,” says Mabuse.

But when Harari travelled, they were also able to assist the struggle with more than empowering musical messages. They carried letters and even concealed fleeing young rebels. “I think what sustained us,” says Mabuse, “was the interactive process between what we were doing with the university students, with the political movement, and being able to adapt to what was happening.”

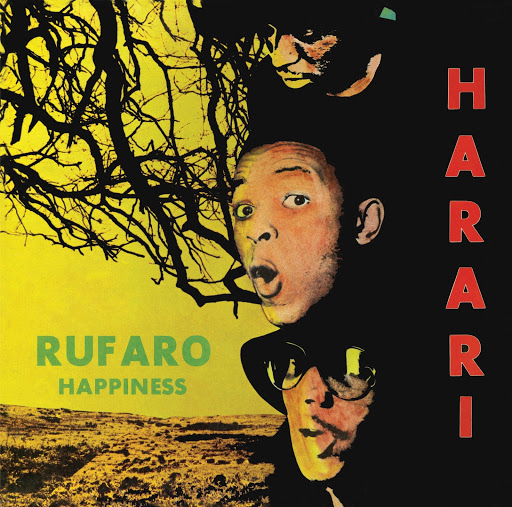

Hidden between the “happy music” of Harari’s Rufaro/Happiness was a confident African politics

Hidden between the “happy music” of Harari’s Rufaro/Happiness was a confident African politics

Lead guitarist Monty “Saitana” Ndimande quit: he wanted a solo career. Masike “Funky” Mohapi, a graduate of the Flaming Souls, joined.

Harari went into the studio late in 1976 to record their follow-up, Rufaro/Happiness. As well as expressing confident African politics, Khaoli recalled, they were pioneering in demonstrating that such messages could also be carried by “happy music. During apartheid times we made people laugh and dance when things weren’t looking good.”

Their ties with the older jazz community were strong by now, and among the stars they invited to guest were alto saxophonist Kippie Moeketsi and guitarist Themba Mokoena.

The album opens with Oya Kai (Where are you going?), a title that also had been borne by some of the early marabi tunes of the 1930s. In this case, the song is an mbira-led unaccompanied chant segueing into Afrobeat rhythms, call and responses, invocatory yells and whoops, and psychedelic improvisation.

In the aftermath of 16 June it was courageous music, alluding sonically to the new, independent African continent. (For apartheid’s censors it may have sounded comfortingly “tribal”.) Harari’s members were in no doubt as to their message: “emancipating Black people through the strength of song,” Mabuse calls it.

But radio stations, even under the most stringent censorship, could also find tracks to play safely. Khaoli described the strategy: “In Harari [and later in my band Umoja], if we wrote songs about apartheid we would disguise them. If we had used the language as it was, we would get arrested,” he says.

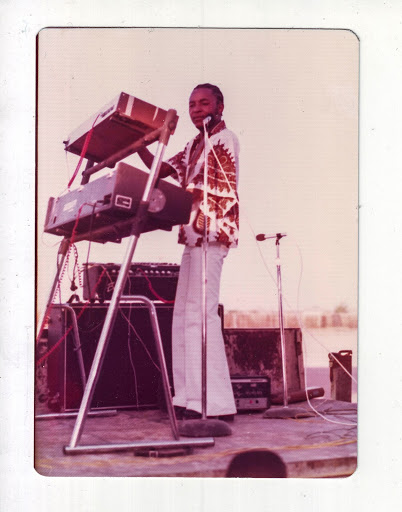

Keyboardist, guitarist and singer Selby Ntuli, one of the band’s founding members, died suddenly in 1978. (Courtesy of the As-Shams archive)

Keyboardist, guitarist and singer Selby Ntuli, one of the band’s founding members, died suddenly in 1978. (Courtesy of the As-Shams archive)

The Harari formula worked, and all the time its members were growing their skill and range. The band were so successful, that in 1978, trumpeter Hugh Masekela invited them over to tour the US with him. But on 2 February 2 that year, Selby Ntuli suddenly died in his sleep, aged only 28. “There had been a series of tragic family deaths,” recalls his niece, jazz pianist Thandi Ntuli, “and growing up I saw how much it had hurt the family. After that, it became painful for everybody to talk about him, despite his achievements.”

US tour plans were abandoned, and Mabuse took over the leadership. In the years that followed he drew in innovative young talent from many other bands, such as keyboardist Thelma Segone, jazz guitarist Doc Mthalane, percussionist Oupa Segwai, organist Babas Ndlovu, guitarist Condry Ziqubu and, by the early ’80s, vocalist Lionel Petersen.

It was a formula that kept the band’s appeal growing. In 1979, Harari were the first Black band to appear on the SABC. Their discography grew: Genesis (1977) and Manana (1978) Kala Harari Rock (1979), and Heatwave and Harari (both 1980). And in 1980, as well as achieving success in the US with the single, Party, Harari were the first Black band to headline their own show at Johannesburg’s Colosseum Theatre.

All that success, however, meant the end of an important partnership. Gallo executives, who, in 1975 had not been prepared to look at the youngsters of The Beaters without the say-so of a talent scout, had become only too keen to sign them.

“It’s the way of the world,” sighs As-Shams label boss Vally. “After the success of those first two albums, Gallo used the muscle that it had — way more than a small label like mine! When my contract with the group ended, they migrated to Gallo.”

Although the struggle was continuing, and intensifying, apartheid’s attitude to cultural controls was shifting. State ideologues were beginning to see the possibilities of relaxing certain restrictions to create distractions and a more acceptable overseas image.

Bass player Om Alec Khaoli would later establish the band Umoja. (Image courtesy of the As-Shams archive)

Bass player Om Alec Khaoli would later establish the band Umoja. (Image courtesy of the As-Shams archive)

Although Mabuse and Khaoli remained unapologetic about their assertion of African identity, the bands around them were changing, sometimes becoming more about showmanship than music or identity; generating a flamboyant, synth-heavy style eventually called “bubblegum”.

Personalities and attitudes to repertoire began to clash within Harari. Looking back, Mabuse admits that “In a way, I became a dictator. When we were listening to The Beatles, I wanted us to be better than the Beatles; when we [were] listening to new things, I wanted us to be better than those too.”

There were resignations, and Harari finally broke up in 1982 —although there have been a fair number of revivals since, many spearheaded by Mabuse. But the break-up was by no means the end of the Harari story: its legacy shaped just about all the important bands of the 1980s and beyond, and fed into the continuing cultural struggle.

Khaoli founded Umoja and created his own recording studio; Segone became part of the all-female Chess; Mthalane and Segwai began Kabassa; Babas Ndlovu joined Ray Phiri and Nana Motijoane in Stimela. Their hit, Whispers in the Deep, was an anti-apartheid anthem for the decade. Kaya Mahlangu followed the route of jazz innovation, with Spirits Rejoice and then Sakhile.

Mabuse created massive hits, and deepened his involvement in the anti-apartheid struggle, using every overseas trip to carry intelligence and resources in and out of the country. “I realised: ‘Hey, you are sleeping through a revolution. There is much more you can do!’” says Mabuse.

Harari’s sound drew on ‘the parallel cross-influences of the Black Power movement and Black Consciousness via African American soul music and Soweto Soul. (Image courtesy of Sunday Times)

Harari’s sound drew on ‘the parallel cross-influences of the Black Power movement and Black Consciousness via African American soul music and Soweto Soul. (Image courtesy of Sunday Times)

He thinks it was that intersection of music, defiant politics and African pride that made Harari’s legacy so formative, even as apartheid was ending: “The parallel cross-influences of the Black Panther Movement and Black Consciousness via African American soul music and Soweto Soul contributed to the way Harari became purveyors of all the musics we today call Afrosoul, Afro-pop, Afrojazz and so on in this country.”

But does it still speak to younger generations? Thandi Ntuli says an emphatic yes. “That cosmopolitanism, that eclecticism — some of our greatest music grew from that era. You can never say it’s just one thing. There’s a fluidity that’s very reflective of township life, even today. There’s an assumption those amazing people who played classical music, painted, wrote poetry, played rock guitar, sang in choirs, all in the same life, were outliers — but that’s the culture of Soweto!

“Jazz continues to hybridise today, and that’s what we hear when we listen to Harari, who were so unforced in seeking and finding an African global identity,” she says.

“Harari’s music still speaks directly to one of my goals as a younger artist: to express myself as an African without pretending that I don’t have all these other musical elements — classical, jazz, house — inside me.”

Or, perhaps as Mabuse expressed it in the lyrics to his 1989 Soweto Uprising tribute, The Chant of the Marching: “Someday when they tell our story/ Children will learn from our past.

A longer version of these liner notes appears on the sleeve of Harari’s Rufaro/Happiness, re-released by Matsuli Music. Also re-issued by Matsuli Music is The Beaters’ Harari album. For more information, visit matsulimusic.bandcamp.com