Dambudzo Marechera in his flat in Harare, possibly in 1985. (Tessa Colvin)

In They Called You Dambudzo: A Memoir (Jacana, 2020), Flora Veit-Wild opens a gloomy window onto her private life, her relationship with Dambudzo Marechera and Marechera’s own life as seen by the author. According to Veit-Wild, the memoir is motivated by a question that an audience member asked her during a symposium in honour of Marechera: “So what was your real relationship to him?”

However, as the work answers this question, it is animated by a deeper anxiety. Veit-Wild is concerned about persistent accusations that she has “made money and reputation out of [her] affiliation with Marechera.” Seeking to put ongoing criticism to rest, the memoir represents an apologia pro vita et opera sua, a defence of the author’s own life and work. Yet Veit-Wild’s attempt to set the record straight backfires as They Called You Dambudzo reveals itself as a deeply disturbing narrative that indicts, rather than exculpates, its author.

The opening chapters establish Veit-Wild as a politically active young woman, member of the Communist League of West Germany, and greatly concerned with “the effects of colonialism and imperialism in Africa.” Barred from civil service in Germany in the 1970s for their “intense political activism,” Veit-Wild and her husband Victor eventually move to Zimbabwe, where he could conduct research with the goal of re-entering academia. Zimbabwe was an obvious choice, Veit-Wild writes, as the couple “had campaigned strongly” for its independence.

Despite her activism, Veit-Wild’s account of her time in Zimbabwe casts a shadow onto her racial politics. The author is dismayed when she arrives in Harare. The city, she writes, “felt very European … Everything was clean and orderly.” Cleanliness and order are not traits that she thought an African city could possess. Soon, the Wilds buy an “other-worldly property, which covered two acres.” Did Veit-Wild feel guilty for living in a mansion, “with domestic workers who called me ‘madam’ and my husband ‘baas’… ?” No, she candidly responds, “I felt exuberant.”

For all their interest in Marxism and decolonisation, when the Wilds visit the colossal estate of a white Zimbabwean farmer and friend, they remain silent about “the unethical conditions under which his labourers lived.” Rather than grappling with how her silence sustains racial inequality, Veit-Wild projects guilt onto Black people themselves, arguing that “those freedom fighters whom we had supported had some of the historical guilt on their side.” Uneasy in a Black-majority country by Veit-Wild’s own admission, the Wilds move around all-white friendship circles. Black people enter their home only as servants — that is, until Veit-Wild meets Marechera.

About her first date with Marechera, Veit-Wild writes: “I felt good with him, though not infatuated; his appearance was just too weird. At times, he reminded me of a lurking animal.” This statement is one of many dehumanising descriptions of Marechera, whom Veit-Wild does not hesitate to call a “hunted animal,” “spoilt brat” and “galling scoundrel.”

Did Veit-Wild, a fellow white woman, confront her racial privilege and the inequality within her relationship with Marechera? The memoir suggests that she did not and, in fact, resented Marechera’s poverty. What is more, Veit-Wild asserts that Marechera’s work freed her of “that terrible conundrum of RACE.” Yet as Veit-Wild believes that she has been liberated from the binds of racism, her own work cannot escape it.

Flora Veit-Wild and Dambudzo Marechera in the garden of the Veit-Wilds’ family home in Harare, Zimbabwe, 1985. (Lourdes Arruti)

Flora Veit-Wild and Dambudzo Marechera in the garden of the Veit-Wilds’ family home in Harare, Zimbabwe, 1985. (Lourdes Arruti)

They Called You Dambudzo mobilises the genre of the memoir to reinscribe capture. It must not be taken for granted that Dambudzo Marechera is in the title, on the cover, and all over the book although this is, and can only be, Veit-Wild’s memoir. There is no such thing as a single-authored “memoir with a ‘double heartbeat,’” as Veit-Wild describes her book. Marechera’s heart is no longer even beating.

Veit-Wild’s name emblazoned across Marechera’s chest on the cover image visually foreshadows how capture defines the work. Veit-Wild respects her former husband enough to accept that she “cannot speak for him.” To the late Marechera, though, she says: “I had to think and speak for you after you kicked the bucket.” So completely has Veit-Wild laid claim over Marechera that she incorporates sections of his poems without even providing the title and source for each individual work. It would have been easy to include detailed footnotes, rather than listing Marechera’s books only in the acknowledgments.

The capture does not stop here. After Marechera’s death, Veit-Wild visits his mother to collect biographical information on the late writer. Veit-Wild admits that Marechera would have disapproved: “‘Why did you even go to see her,’ I hear you shouting out of your grave. ‘She was a slut!’” Clearly, Veit-Wild sees nothing wrong with putting words into Marechera’s mouth. Not even Marechera’s mother is safe from Veit-Wild.

Neither are his brothers. “When I looked into his face,” Veit-Wild writes about Michael Marechera, “I saw features of Dambudzo, but a different version of him, mouse-like …” About Nhamo Marechera, she writes: “I find it hard to evoke a distinct image of your younger brother. In my visual memory I see a cagey animal in front of his burrow, all defence and attack at the same time, ready to run or to hiss and hit.” The animalistic images that Veit-Wild uses to describe Black people cannot be overlooked.

Veit-Wild does not shrink away from providing the most humiliating information about Marechera. She really wants us to know that he once released “the many litres he had been drinking” in his sleep. No wonder that Marechera wrote about Veit-Wild, “I realise how much / I could not have loved her.”

Having pushed Marechera to the outskirts of humanity and confined him to the status of a “penniless poet” who “needed help,” it becomes easy for Veit-Wild to emerge as a superior saviour in her own narrative. Anxious about having been accused of profiting from Marechera and his work, “of making money and a name out of appropriating you,” Veit-Wild is set on turning the narrative on its head.

She thus depicts herself as a magnanimous benefactor and Marechera as nothing less than an ungrateful “parasite.” Addressing Marechera, she writes: “You would always bite the hand that tried to feed you.” The hand that did the most to feed Marechera is Veit-Wild’s own, the author wants us to believe.

…

A student photo of Dambudzo Marechera. (New College, Oxford/Dambudzo Marechera Trust)

A student photo of Dambudzo Marechera. (New College, Oxford/Dambudzo Marechera Trust)

The memoir is thus filled with a seemingly endless litany of things that Veit-Wild gives to and does for Marechera. Already in the prelude, Veit-Wild recounts how Marechera asks her for money to pay for a taxi. Not content to tell us this irrelevant detail once, Veit-Wild returns to it in a chapter titled, without irony, “The Taxi Has to be Paid.”

About Marechera landing in the hospital and having a severe post-surgery haemorrhage, Veit-Wild has this to say: “I only knew that I paid the costs for his stay and treatment at the Montagu Clinic. A receipt for over a couple hundred dollars from that time emerged among my papers.” This noisome detail, too, is repeated twice. Veit-Wild insists that she not only provided financial assistance, but also opened many doors for Marechera, whom she calls her “protégé writer,” while she describes herself as “his lover and sponsor in one.” The white saviour narrative that structures the memoir is too glaring to be missed.

White saviours, of course, are not disinterested benefactors. Their gestures are emblematic of what Paulo Freire in Pedagogy of the Oppressed calls “false generosity,” which “is nourished by death, despair, and poverty.” After various evenings spent having sex in hotels, Veit-Wild decides to host Marechera, who is homeless, in a cottage on her family property. When Veit-Wild gets tired of Marechera, he confronts her: “You want to expel me? Where should I go? Back in the streets?”

The narrative continues as follows: “As always, he was a master of emotional manipulation, making everyone else feel guilty for the misery in his own life. I was exasperated. ‘Why do you not do anything to stand on your own feet?’ I said. ‘You always depend on other people. You are a parasite, a bloodsucker. I do not want to see you again!’ … Why could I not just leave Dambudzo to his own way of destroying himself?”

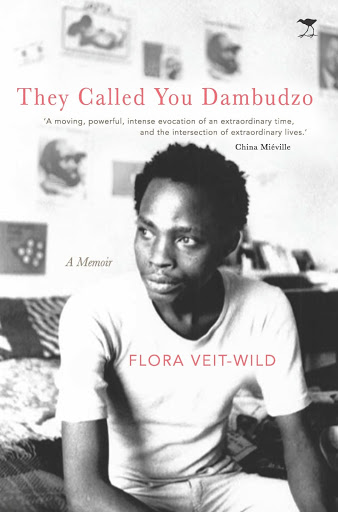

The cover of Flora Veit-Wild’s memoir They Called You Dambudzo.

The cover of Flora Veit-Wild’s memoir They Called You Dambudzo. Here and elsewhere in the memoir, Veit-Wild takes no responsibility for her actions towards Marechera. That her behaviour is abusive is unthinkable for Veit-Wild. She can see only his abuse, but never her own. And yet, she insults him and treats Marechera like an object, ready to throw him out in the streets when she wants to have “a quiet Christmas with our visitors.”

Marechera, the memoir suggests, knew that he was disposable. “You are just exploiting me; you only want to get hold of my writings” he tells her, “All you want is my black dick and then you run back to your people.”

And who can blame him? Veit-Wild, who remained with her husband throughout her affair, herself seems unsure about why she was involved with Marechera. But one thing is clear: She “did not want to see such talent go to waste through his self-destructive behaviour.” She had to save Marechera from himself. The duplicity abounds as Veit-Wild argues that she wanted to get Marechera “off drink,” yet carries “a hip flask of sherry” to spice up their sexual encounters or puts gin in Marechera’s water, unbeknownst to him, to loosen “his tongue” before a lecture she organised.

And Marechera’s manuscripts? Veit-Wild writes that Marechera asked her for pen and paper, on his deathbed, because he wanted to write a will. She told him to wait until tomorrow. Marechera died the next day. Veit-Wild was not there at the moment of Marechera’s passing, yet she writes, more than once, that she “had seen him die.” She did have the keys to his flat, for which she paid the rent, as she makes sure to tell us, and collected Marechera’s writings upon his death.

Once published, the work allowed Veit-Wild to quickly become a professor, which was inconceivable in Germany for someone who had recently earned a doctorate degree. About this fact, Veit-Wild writes: “Had it not been for you, Dambudzo, my irreverent, spiteful friend and mentor, had you not appointed me to execute your unwritten will, it would not have happened. I would not have become a person of such reverence as was the Humboldt professor of African literature.”

However, Marechera did not appoint Veit-Wild. Neither did he “bequeath [her] the legacy to revisit his life.” That Veit-Wild claims that Marechera did, although she shows otherwise, is not just contradictory, but profoundly perturbing. As I exit the book, Marechera’s words to Veit-Wild continue to resonate in my mind: “No, you do your work. Don’t try to exploit me.” I cannot shake the feeling that Marechera knew what was coming.