Matthew Krouse receives mouth-to-mouth resuscitation for an army medical manual, 1984. (Image courtesy of Matthew Krouse)

Earlier this year, Adam Broomberg, a Johannesburg-born artist living in Berlin, phoned Matthew Krouse, a former actor turned writer and editor, with a request. It didn’t involve Yiddish translation work.

“People seem to think I am Isaac Bashevis Singer, which I’m not,” says Krouse, who was born into a Jewish family from Germiston in 1961. He grew up speaking Yiddish with his mother and has previously helped Broomberg with translations. “I won’t ever win a Nobel prize for writing in Yiddish,” he insists in reference to the Polish-American writer’s 1978 accolade.

Broomberg revealed his reason for calling Krouse in increments. He started out by asking if he knew about Clubhouse, the social-media app used to host audio chats. Krouse, a man of uncommon creative accomplishments in performance and publishing, responded no.

Nonplussed, Broomberg recruited him into a chat about nonfungible tokens (NFTs), cryptographic units of data used to verify the uniqueness of ephemeral digital and video art. Krouse uses piquant language to describe this new-fangled technology. Nevertheless, and in deference to Broomberg, whose artistic career he promoted during a three-year stint working at the Goodman Gallery, Krouse agreed to play along.

After the Clubhouse hangout, during a private chitchat, Broomberg asked about the whereabouts of the underground films Krouse had been involved with in the 1980s. Krouse doesn’t know. His personal archive includes only VHS cassette recordings of the urgent, austere and visceral films he collaboratively nurtured and contributed to.

“I was shocked,” says Broomberg. His disbelief soon morphed into action. In a timely act of recovery Broomberg has devoted the entirety of his current solo exhibition at kunsthallo, an online gallery, to showcasing Krouse’s films. The exhibition is even named after Krouse, whom Broomberg first met in The Dungeon, a gay nightclub he frequented as a teenager in 1980s Johannesburg.

The short parody film De Voortrekkers features simulated gay sex, the collapse of the Voortrekker Monument and Krouse’s Jewish-Afrikaans father playing the role of pioneer patriarch. (Courtesy of Matthew Krouse)

The short parody film De Voortrekkers features simulated gay sex, the collapse of the Voortrekker Monument and Krouse’s Jewish-Afrikaans father playing the role of pioneer patriarch. (Courtesy of Matthew Krouse)

The exhibition includes digitised versions of two films banned in 1987 by apartheid censors. The short parody film De Voortrekkers features simulated gay sex, the collapse of the Voortrekker Monument and Krouse’s Jewish-Afrikaans father playing the role of pioneer patriarch.

The Andrew Worsdale-directed feature Shotdown is a hot mess of ideas set in the white demimonde of Yeoville and was co-written by Krouse. The exhibition also exhumes rushes from The Soldier, an unfinished short film about militarism and male rape conceived by Krouse.

“It is funny to have a mid-career retrospective of a no-career,” says Krouse.“It is right but it is wrong, this whole thing.”

As part of the exhibition’s marketing, Krouse is sensationally billed as “the most censored man in apartheid South Africa”. The claim is somewhat overwrought, especially if one consults entries in Jacobsen’s Index of Objectionable Literature, a voluminous apartheid-era handbook of censored books, films, music and more, but it nonetheless helps to pin the timeframe and zeitgeist of the work.

Krouse was a provocative artist and cultural activist whose work in the 1980s was serially banned by a state that also criminalised political dissent and gay love. That Krouse isn’t more widely known and celebrated for his ribald satire and daring agitprop work is a state of affairs Broomberg has explicitly set out to investigate in his current exhibition.

Broomberg’s interest in Krouse’s films, and the extraordinary personality that lurks behind them, has much to do with his recent work exploring gender and normativity in an increasingly digitised art world.

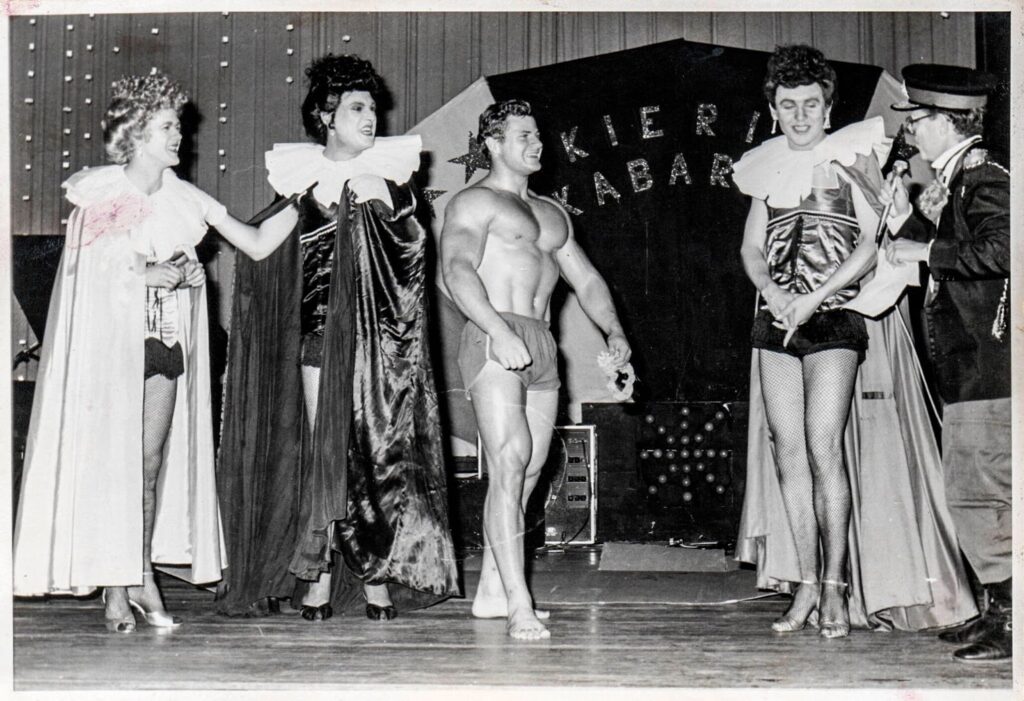

An Arista Sisters performance at Voortrekker Hoogte, September 1984. (Courtesy of Matthew Krouse)

An Arista Sisters performance at Voortrekker Hoogte, September 1984. (Courtesy of Matthew Krouse)

In the past year Broomberg has eavesdropped on Clubhouse chats and lurked around Decentraland, an evolving virtual world and marketplace powered by the Ethereum blockchain. He has gained a reputation as a gadfly because of the uncomfortable questions he asks about the normative biases informing these environments.

“The NFT world is run by middle-aged, white, hetero-normative men,” says Broomberg. Two of his recent projects animate this critique. Last year Broomberg collaborated with transgender activist and artist Gérsande Spelsberg, aka Gigi, to produce a unique artificial intelligence-generated portrait of Spelsberg’s transformation from man to woman. The mutating portrait, which was tokenised using a digital verification company, recently sold to an online bidder for R120 000 — a paltry figure when compared with some of the gaming graphics masquerading as art in the NFT metaverse.

The other project is his elegant digital hustle aimed at providing Krouse with an international platform. As part of the programming for his kuntshallo exhibition, Broomberg invited author and journalist Mark Gevisser to engage in an online conversation with Krouse. The talk yielded some insightful anecdotes.

Krouse was Nadine Gordimer’s amanuensis (literary assistant) when she received the 1991 Nobel prize. He edited and co-designed Lesego Rampolokeng’s first book. He painted banners for trade union federation Cosatu.

Another titbit from the conversation relates The Invisible Ghetto (1993), the first-ever anthology of lesbian and gay fiction from South Africa. Krouse, who was working at the Congress of South African Writers at the time, jointly edited the book with printmaker Kim Berman.

The Invisible Ghetto includes Krouse’s short story The Barracks are Crying. The work substantially draws on his personal experiences of being a military conscript sequestered in a platoon of gay men. The story rehearses a triad of themes that energised Krouse’s cabaret performances and film pieces of the 1980s: white masculinity, militarism and libidinal energy.

Krouse’s stint in the military is central to his early biography as an artist. “I couldn’t leave the country to avoid the army, as my family wasn’t wealthy,” he says.

After completing his basic training Krouse joined the army media centre. He worked as a scriptwriter and produced training videos and slide programmes on nursing procedures. He also joined a military-approved drag troupe, known as the Arista Sisters, that did a Fats Waller routine involving a muscleman, wigs and high heels. The troupe ended up touring nationally, even performing for medal-festooned grandees and then-president PW Botha’s wife.

“Female impersonation has been one of the basic forms of entertainment in barracks, prisons and sometimes even in schools,” wrote Krouse in a 1994 essay in Defiant Desire, a book of nonfiction co-edited by Gevisser and Edwin Cameron. “Armies and institutions allow — and sometimes even encourage — a brief and public display of momentary transgression. It is a sanctioned assertion that there is otherness, an assertion of who the other is.”

It was during his time in the military that Krouse also met producer Jeremy Nathan and cinematographer Giulio Biccari. The trio hatched plans for a film commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Great Trek, which they named De Voortrekkers after a 1916 film of the same name. Their script was later seized during a police raid on Krouse’s home, along with photos of him sprawled naked at a monument to a fallen soldier.

Starting in 1985, Krouse routinely found himself in trouble. Famous Dead Man, his bawdy two-person cabaret act with Robert Colman commemorating the life of Hendrik Verwoerd, was banned. So too Noise and Smoke, his 1985 anti-conscription cabaret piece with Colman featuring a stolen slide of a grossly wounded soldier.

Famous Dead Man staged in Shot Down in 1987 with L Megan Kruskal as Betsy Middle, Matthew Krouse as Tsafendas and R Nicky Rebelo as Verwoerd. (Courtesy of Matthew Krouse)

Famous Dead Man staged in Shot Down in 1987 with L Megan Kruskal as Betsy Middle, Matthew Krouse as Tsafendas and R Nicky Rebelo as Verwoerd. (Courtesy of Matthew Krouse)

Shotdown, which features Krouse and Colman re-enacting scenes from Famous Dead Man, was banned in 1987. A similar fate befell De Voortrekkers when it was completed that year too.

These experiences, while initially energising, ultimately unsettled Krouse. “There I was, a prematurely productive young artist, who was really battling with shit.” He found solace in a drug addiction.

Drawing on his skills as a media officer clandestinely involved in the organisation of Nelson Mandela 70th birthday tribute concert at Wembley Stadium in London in 1988, he transitioned into writing and editing. For 16 years Krouse was the Mail & Guardian’s arts editor. He currently works as a freelance writer and art consultant.

“I just couldn’t make the jump, I couldn’t go from the one place I was successful — making statements that hurt people and disturbed them and unsettled them, which was the function of art — and then go on and make a commercial career.”

But Krouse, who likens himself circa 2021 to the early Johannesburg outlaw William Foster holed up in a cave, is not resentful or regretful. He defiantly remains an “outrageous homo” awed by the tradition of “dirty queens”.

His films have quietly cultivated a mythology that he feels is true to the history of underground filmmaking, which is “more about the possibility of the existence of that kind of film rather than its actual material essence”, as he told Gevisser.

In short, he is not nostalgic. The past, after all, is a failed country. Wistfulness, he cautions, is fatal. “It is a repulsive thing because what you are nostalgic for is your oppression, or at least, in our situation, the oppression of others. There is no use walking around saying of the 1970s and ’80s, it was the best of times and the worst of times. It has to be framed within the broader discussion that is being held now.”

What is that discussion? “You may say apartheid is over, but there is still a lot of work that has to be done.”

He points to the four women who brandished modest posters reading “I am 1 in 3”, “#”, “10 years later”, “Khanga” and “Remember Khwezi” in front of then-president Jacob Zuma in 2016. “That is activism and performance. That is fearless. Who knows what would happen to them? That was in the same mould or spirit that I, we, did things.”

Adam Broomberg’s exhibition Matthew Krouse runs until 7 May at kunsthallo.com.