Is this the beginning of the end of all human-created art? This is the question implied by Vulane Mthembu’s AI album Nguni Machina. (Photo by: Kgune Dlamini)

A remixer and producer who has worked with the likes of Moonchild Sanelly, Spoek Mathambo, Busiswa Gqulu, MXO, and Helsinki Headnod Convention, Vulane Mthembu’s latest horizon is an experiment in how artificial intelligence (AI) and art are the new creative frontiers.

Mthembu made what is possibly an African first; the shortest (five minutes-long), fully AI-generated music album released under creative commons. He called the album Nguni Machina — referencing the shared heritage and languages of the Nguni people, as well as the Latin phrase “Deus Ex Machina” (god in the machine). He named the tracks after seismic cultural and scientific developments, like Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot, Boson particles and cryptocurrency nonfungible tokens (NFTs).

And, just like that, he placed himself — and South Africa — in the centre of a Venn diagram of some of the most critical questions for this generation of artists: “If a computer can make excellent (or, at least, objectively acceptable) art – what do the artists do to stop themselves becoming Luddites powered by misplaced nostalgia? Are we the next steam train or horse and carriage? Who are the real gatekeepers of taste and creative excellence? Who owns AI-generated work? Do we need to factor universal basic income for artists into the running costs of AI-generated art? And is the future of ‘real art’ a plugin or patch we can run that inserts simulated fingerprints and imperfections, assuring our audience that at least the shadow of the artist is still present?”

“The initial motivation for the Nguni Machina project was driven by curiosity: how compelling or ‘good’ can AI-generated music sound in 2021?,” says Mthembu. “As this was, in itself, a very subjective question without a clear-cut answer (due to how we as humans respond to art), I had to establish some form of yardstick to gauge the success of the project.”

Using the Turing test as his methodological framework (a test that measures the appearance of intelligence from a computer’s output to be equal to or indistinguishable from a human’s), he proposed that his metric of success for Nguni Machina wouldn’t be how many people streamed it or whether they “liked” it: it would be if people listened to the music and couldn’t tell if the music was made by AI.

The Maestro dataset and Wave2Midi2Wave by Magenta Tensorflow

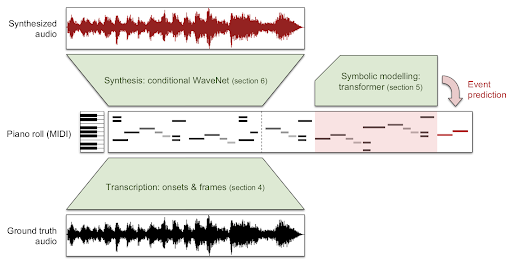

The Maestro dataset and Wave2Midi2Wave by Magenta TensorflowThe project was created using Google’s Magenta (an open-source research project exploring the role of machine learning as a tool in the creative process) and MuseNet AI, a deep neural network that can generate musical compositions from collected training data from many different sources. Using large collections of MIDI files spanning several genres, Mthembu overlaid a Maestro dataset and waited to see what the machine had to say.

He insists: “It was important that I did not interfere with the AI in any way nor introduce any human assistance in the complete album creation process: from composing and arranging to mixing and mastering … it was all done by the machine.”

This is not new. Babusi Nyoni’s Gqom Robot is an exciting example of what is possible if we let the robots run free in popular culture. But Mthembu’s proposal is shattering. Humans have mostly used 10 fingers to play or write or paint or draw: but AI has unlimited fingers (and knows what appeals to humans). It can inform and inspire artists who want to surface current insights, connections, or patterns across a large set of data points — like the trending emotions and collective zeitgeist of every person connected to every square inch of data in any given sub-set, simultaneously, in a matter of minutes.

In the album, there are flourishes of artistic brilliance in some of the pieces, unexpected Easter eggs of sounds, beats and riffs you’d almost swear you could recognise. But there’s also a lot of something completely disarming, even jarring. In the end, it leaves the listener with lingering questions: Do I like it? Should I like it? Am I, as an artist, a traitor for even listening to it in the first place?

On 26 May Mthembu will be giving a talk about issues arising out of his sonic experiments with music lecturer Neil Gonsalves and students at the KZN School of Jazz and Popular Music. The talk runs from 9.30am to 10.30am.

You can stream it on Zoom by using this link.

A photographer, gamer, coder, open data advocate and mathematics and science educator, Mthembu is a founding member of Big Fkn Gun.