Reminiscences: Fruit hawkers plied their trade on the streets of District Six in 1972. (Photo: Jan Greshoff. Copyright: Kathy Abbott, Martin Adrian & Robert Greshoff)

The book District Six: Memories, Thoughts and Images, compiled and edited by Martin Greshoff, is a collection of autobiographical stories and poetry written by former District Six residents. The personal accounts and reflections create a narrative made up of many different voices and perspectives.

The book’s contributors consist mainly of “lay” authors, using the varied dialects of Afrikaaps and Mengels, alongside standardised versions of English and Afrikaans, adding to the linguistic depth and richness, and an earthy flavour to the text.

These first-hand accounts are darned together by the photography of Jan Greshoff, a Dutch-born architect who resided in Cape Town.

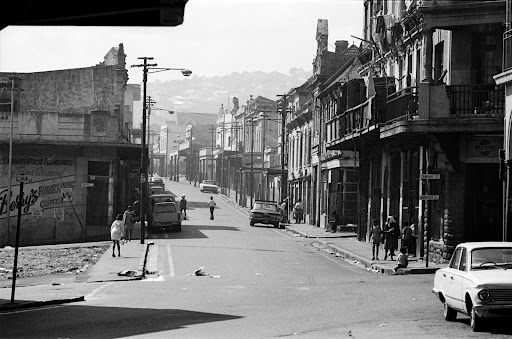

Landmarks erased: A view of Hanover, Tennant and Godfrey streets. (Photo: Jan Greshoff. Copyright: Kathy Abbott, Martin Adrian & Robert Greshoff)

Landmarks erased: A view of Hanover, Tennant and Godfrey streets. (Photo: Jan Greshoff. Copyright: Kathy Abbott, Martin Adrian & Robert Greshoff)

The photographs and stories in the book are a period piece, capturing the tail end of an era that spanned a century, beginning with the manumission of slaves in the mid-19th century, and ending in the enforcement of the Group Areas Act, declaring racial apartheid and the segregation of residential and business districts across South Africa. Between 60 000 and 80 000 residents were forcibly removed from District Six and into various townships on the Cape Flats between the 1960s and 1970s.

The authors would have been children at the time of the demolitions; most of the stories and poems are tinged with the sadness that accompanies never having had stability, continually living under the threat of impending doom and, thus, always somewhat bittersweet.

There is a romanticism that accompanies many childhood memories, but also depictions of brutality and the witnessing of acts perpetrated by members of community and state, which have clearly marked the memories of the contributors, and creates a lasting impression on the mind of the reader.

The junction of Longmarket, Hanover, Tennant and Upper Darling streets in District Six in 1972. (Photo: Jan Greshoff. Copyright: Kathy Abbott, Martin Adrian & Robert Greshoff)

The junction of Longmarket, Hanover, Tennant and Upper Darling streets in District Six in 1972. (Photo: Jan Greshoff. Copyright: Kathy Abbott, Martin Adrian & Robert Greshoff)

Two such descriptions are the witnessing of a rape behind the British bioscope, and the black flag at half-mast at the Roeland Street prison that would signal the hanging of a prisoner on Fridays. Whether positive or negative, the stories detailed are all impactful. In these accounts, there are no former residents of District Six who do not remember the neighbourhood with nostalgia and who would not have preferred to return, for business or love or to live.

The editor’s choice to leave the stories largely untouched in terms of the dialect, feel and even potentially derogatory language in terms of the modern context of language usage is interesting. In doing so, the editors have allowed a more natural and unscripted storytelling — one in which the warts appear to show the diversity of views and even the biased perceptions of the authors — in an actual setting.

The effects of the forced removals are implied rather than attended to in great detail; instead, it is the holding on to memory, to a time that exists solely in the mind and that, within a generation, will be entirely wiped out, that captures the reader.

Constitution Street in 1973. With no visible landmarks remaining, people rely on images and their memories — or those of their parents — to reconstruct what the area looked like before. (Photo: Jan Greshoff. Copyright: Kathy Abbott, Martin Adrian & Robert Greshoff)

Constitution Street in 1973. With no visible landmarks remaining, people rely on images and their memories — or those of their parents — to reconstruct what the area looked like before. (Photo: Jan Greshoff. Copyright: Kathy Abbott, Martin Adrian & Robert Greshoff)

Although the photographs in the book do not portray intimate moments, they serve as catalysts for the outpouring of memory and imagination that may, without the prompt, have been lost in time. Their importance is as an addition to the growing, multilayered intergenerational archive, which captures and memorialises the stories of an ageing generation of former District Six residents.

Without a physical landmark to revisit, they have only their memories to transport them — and us all — back to a much-revered site of inter-racial, mainly harmonious coexistence within a deeply troubled time, against the backdrop of large-scale historical violence perpetuated in the name of crown and colony.

The book’s importance is in compiling a coherent story for generations to come, when living memories fade and all that is left to hold on to are the scraps of decontextualised memories of words, phrases, movements and games passed down.

Sifting through the past

Corner of Pontac St and Russell St, District Six, 1974. (Photo: Jan Greshoff. Copyright: Kathy Abbott, Martin Adrian & Robert Greshoff)

Corner of Pontac St and Russell St, District Six, 1974. (Photo: Jan Greshoff. Copyright: Kathy Abbott, Martin Adrian & Robert Greshoff)

I found myself closely inspecting the photographs from the street my family lived in, in case there was someone there I might have recognised. It was as though that would give me something — one of the missing pieces that was taken away from me; that the silence of the generations before me did not allow me to hold firmly in my mind, in my heart.

I can almost see my grandmother playing in the street. I imagine seeing her as a little girl in her lace-frilled bobby socks and baby-doll shoes, and there — in the place of half-memory, half-dream — a place we can meet and play together, jumping rope, playing kennetjie.

My great-grandmother in her fancy Sunday outfit and high-heeled shoes, standing on her stoep and smoking a cigarette, watching the children and talking to a neighbour. The smell of koesiesters in the air, or of curry cooking in the neighbour’s kitchen. And then I remember that the photos were taken in the 1970s, and even though I wasn’t born yet — my mother was a teen, having grown up in Bonteheuwel — and that the dream never was mine because our family had been moved along by then, dispossessed in ways that cannot be named, because they have gone to the grave with my grandparents and the generations before them. — Janine Lange

The list of outlets are as follows (Most should be able to send nationally):

1. District Six Museum Bookshop (25a Buitenkant Street),

2. Select Books (56 Surrey Street, Claremont),

3. Clarkes (199 Long Street),

4. The Book Lounge (71 Roeland Street),

5. The Heritage Shop (19 Queen Victoria St)

6. K and R Mobile Store, Belhar (Tel: 0836681836) free deliveries – 20km radius.

7. Timbuktu Books (19 Golf Course Rd, Sybrand Park)

8. Bokmakiri Books (Swellendam)

9. The Kirstenbosch Bookshop

10. Bay Bookshop (B6 Mainstream Centre, Princess Street, Hout Bay)

This is an extended version of an article initially published on thedailyvox.co.za.