Retrospective: The author’s maternal grandfather Ismail Vally posed for a formal picture surrounded by his wife and children.

The Oriental Plaza, a vast shopping mall in Fordsburg housing 360 traders, was built in the 1970s. As part of apartheid spatial planning, traders who had established businesses in 14th Street, Fietas, were forced to move to the Oriental Plaza and rent shops at exorbitant rentals. The ultimate purpose of this planning project was to turn Fietas into a whites-only area.

Entering into negotiations to get the buy-in of the traders, who ran successful businesses, would have given them a false sense that they had a say, so they were quite literally bulldozed into trading at the Oriental Plaza. This did not happen in one fell swoop, as the Oriental Plaza was built in sections, with the North Mall renting out space to traders first. The Soweto uprisings in 1976 halted the relocation but by then, enough businesses and homes had been bulldozed to make trading in Fietas no longer viable. People of Indian heritage the world over are known for their tenacity, resilience and entrepreneurial spirit, and the traders took on the challenge of making their businesses in the Oriental Plaza successful with grudging determination.

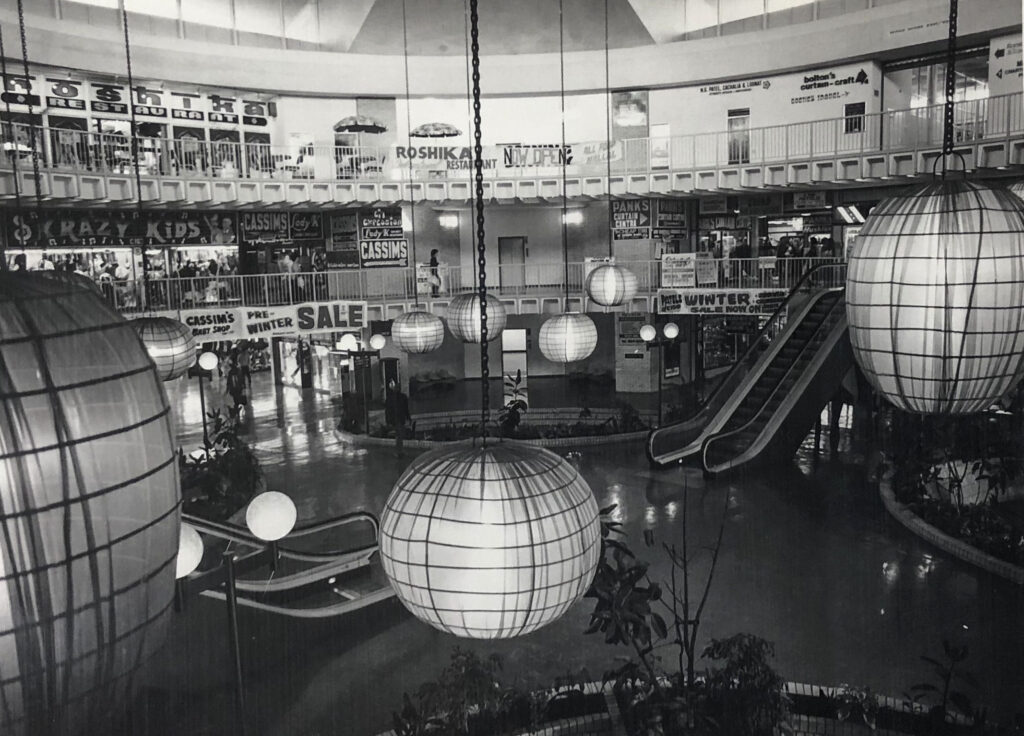

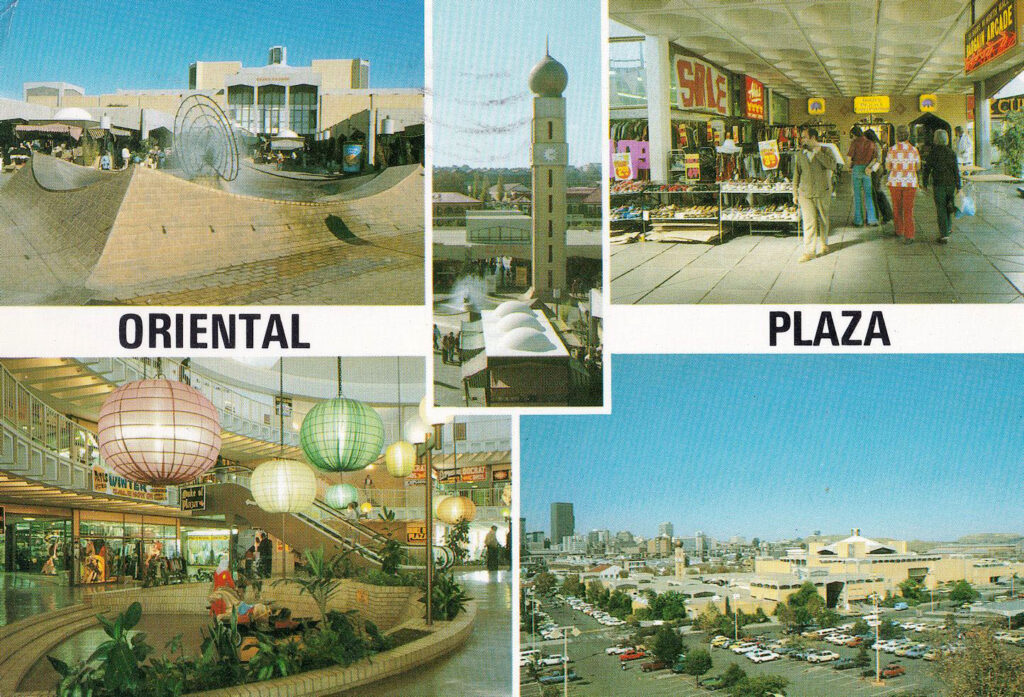

Black-and-white and colour photographs from 1978 show the purpose-built mall, which forced traders out of Fordsburg in order to turn Fietas into a whites-only area.

Black-and-white and colour photographs from 1978 show the purpose-built mall, which forced traders out of Fordsburg in order to turn Fietas into a whites-only area.

In this way, the jazzy, soulful vibe that only a mixture of Malays, Indians, Chinese, Coloureds, Africans, Jews, Lebanese and Afrikaners living in close proximity together could create was replaced by a themed shopping experience, packaged inside a modernist shopping centre that spanned fifteen city blocks.

A rather patronising nod to the Orient was evident in the souk-like marketplace set-up devised by the architects. The gold-coloured brick in the courtyards of the North and South Mall sections and their open air kiosks, as well as the octagon inlays of the arcade ceilings, all worked towards the theme. The Grand Bazaar, a three-storey circular section, was lit by gigantic wrought-iron globe structures covered in ruby-coloured cloth, suspended dramatically from the ceiling with industrial-strength chains.

The Peacock Fountain, a steel bird with fanned-out feathers and water shooting out of pipes, sat in the courtyard of the North Mall, where a clock tower adorned with minarets was erected to orientate customers by serving as a landmark. This minaret lines up almost exactly with the Newtown Mosque minaret on Vorster Street.

White customers would purchase samoosas made for mass consumption and sit on the edge of the Peacock Fountain eating their driehoek koelie-koek. Some of them would ask for samoosas by this name, which perhaps explains why traders sold gigantic, oily samoosas with thick doughy pur which had bubbled from being unlovingly dunked into too-hot oil. No self-respecting Indian would consume that heavy triangle masquerading as a samoosa in their own home. I suspect that the green bullet chillies were not sliced very finely either.

Karma has a name. It was a samoosa purchased at the Oriental Plaza in the 1980s.

My parents and Papa rented Shop 242 in the South Mall. Most traders who moved to the Oriental Plaza from Fietas were general dealers, which meant that a single shop could sell cutlery, bridal fabric and dashboard cleaner. This was part of what made shopping in the hustle and bustle so much fun: one never knew what one might find. By contrast, the developers of the Plaza attached strict conditions to what could be sold in each business. My parents had to introduce a unique line of goods so as not to compete with merchants who were old hands at the trading game.

Despite high rentals, traders made a successful living in the still-famous Oriental Plaza

Despite high rentals, traders made a successful living in the still-famous Oriental Plaza

And so, before flea markets and craft markets, my folks started one of only two curio shops in the greater Johannesburg area. The other one was in the Carlton Centre. My parents depleted their creative juices coming up with the idea of a curio shop and then named it Mystic Curios. Using their surname, Theba, would have been more appropriate – it was an obvious choice that would have lent some quasi-authenticity to the products on offer. They sold wooden African masks, soapstone busts of African men and women, carved wooden elephants, cheetahs, rhinos and almost everything touristy one could think of. For Show and Tell in grade one I took a glass paperweight with grassy mud and a giant orange sticker, which said “100% Pure South African Elephant Shit”.

Zulu love letters were a fast seller, as they were the perfect small token to hand out to colleagues and they were light enough to pack without exceeding the baggage allowance. These gorgeous colourful “letters” were made up of different patterns of colours with each colour chosen to convey a particular meaning. In the early 1980s, every American tourist who visited the Oriental Plaza returned home from their safari in Africa with piles of Zulu love letters. Unbeknown to them, some of them proposed marriage to their bosses.

Large copper plaques with 3D animals against a black painted bushveld setting would render tourists indecisive. They desperately wanted to take these home, but they were bulky and heavy. In a last-ditch attempt to clinch the sale my dad would say, “Phone me from the airport and I will collect it from you and refund your money if it doesn’t fit in your luggage.” In twenty-odd years, we never received a call from Jan Smuts Airport so either those gaudy plaques are adorning homes the world over or there are several hundred of them in an airport storage room.

The price marked on an item was never the price that shoppers were expected to pay and traders enjoyed haggling with shoppers. My dad’s line to shoppers when he was asked for a discount was “You are killing me!” but when he was not asked for a better price, he would offer to “work something out” for them. He would fake-crunch the numbers on a calculator, his profit being quite secure, and then show the customer the screen on the calculator and gesture towards me and say, “My children must also eat.”

Raising a child in a shopping centre is not ideal, but when I was not being a sales prop I busied myself playing the African musical instruments. For fun I would sometimes wear an African mask and walk around the shop nonchalantly when customers walked in, until my mum realised how unsettling this was for customers and she made me promise to stop. On days when my marimba-playing skills grated their nerves, I would take a walk around the Oriental Plaza and visit other shopkeepers.

In the early days of the Oriental Plaza, very few shoppers frequented the new centre. Traders had time on their hands and I would visit and chat. Some traders would regale me with stories about the heyday of Fietas and confide how much they despised living in the dustbowl of Lenasia. I would listen attentively, drinking in all the information. I presume that they were reassured that their stories were being passed on to a younger generation. As I left, they would give me a small item from their shops.

The owner of Discount Cycle and Toys would give me chalk and I called him Chalk-Uncle. The uncle from Everyman’s Luck would give me a tiny ornament to fill my printer’s tray. The aunty from the candy store would give me a Chappies. She was Chappies-Auntie. Sometimes my mum would make me return some of the items, but the traders always insisted that I keep them. It is a cultural thing to send a guest off with a small token for having taken the time to visit. In exchange, and I baulk at this memory, I would sing a song for them. For a reason that is probably equally embarrassing, I knew every word of Boney M’s By the Rivers of Babylon and would belt this song out on request. There is a beautiful age between three and six when precocious children are not yet self-conscious, and it was in these years of my childhood, before school, that the traders in the Oriental Plaza were my family.