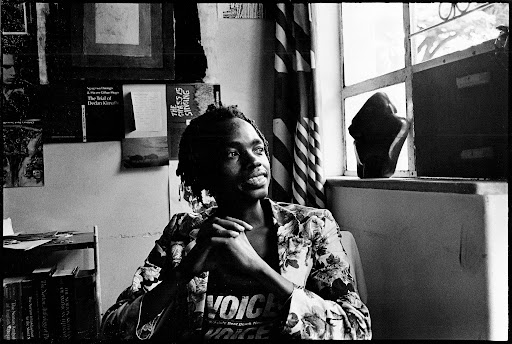

A portrait of Dambudzo Marechera based on a photograph by Ernst Schade. (Painting: Mongezi Ncombo)

Sun-weathered, pirated copies of Dambudzo Marechera’s Guardian Fiction prize-winning debut, The House of Hunger (1978), can be found spread out on cracked pavements under the eaves of Harare’s shops, going for a few smudged US dollar notes. A couple of years ago, as if it were the doing of a beneficent fate — perhaps an accidental archivist had suddenly discovered remaindered copies in an abandoned warehouse — virtually new copies of Marechera’s posthumously published novella, The Black Insider, appeared on the same streets.

In Zimbabwe, where mainstream publishing of fiction has all but collapsed — a mirror of the general decrepitude brought about by the late dictator Robert Mugabe’s rule — the Marechera legend has been kept alive by such unorthodox, make-do means: kukiya kiya, in the local lingo.

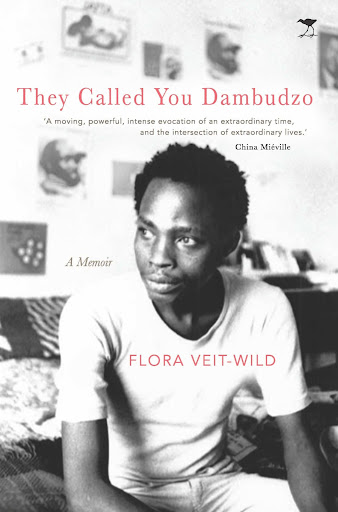

Now, the publication of They Called You Dambudzo, a confessional memoir by the German scholar Flora Veit-Wild about her relationship with Marechera, brings new insights to what was generally thought to have been a biographer-subject affair, but whose ballast, in fact, had been a tempestuous, disease-ridden love affair.

The new details in the memoir mean that, far from retreating from public imagination, the legend of the Zimbabwean writer, who died on 18 August 1987 at 35 years old, will continue to grow even as we approach next year, when he will have been dead for as long as he was alive.

Marechera’s cult in Zimbabwe remains strong. In part, this is because Zimbabweans born long after his death realised that the conditions he wrote of in the title story of the book The House of Hunger — “where every morsel of sanity was snatched from you the way some kinds of birds snatch from the very mouths of babes” — didn’t cease at independence in 1980. Democracy came then, ending a torrid bush war, but freedom stayed behind.

In Europe, on the African continent, and elsewhere, new readers continue to discover a writer who upended the idea of what it meant to be an African writer. “I think I am the doppelganger whom, until I appeared, African literature had not yet met. And in this sense I would question anyone calling me an African writer. Either you are a writer or you are not. If you are a writer for a specific nation or a specific race, then fuck you,” Marechera once said with characteristic caustic wit.

Yet even though the cult remains strong, the fascinating facts and, at times, disturbing details about his life are worth repeating here, because they are receding from the public memory; his contemporaries are dying off and the documentary biography Dambudzo Marechera: A Source Book on his Life and Work (1992), the single biggest fount about his life, written by Veit-Wild, is almost impossible to find in Zimbabwe and in the subregion (if you can find it on the second hand book market, it will not cost less than $50, much more than most working class Zimbabweans earn in a whole month).

Dambudzo Marechera was published locally by the University of Zimbabwe Publications (the primary publisher was Hans Zell, a German publisher). Written over several years and involving some 70 interviews with family and friends, including Marechera’s mother Masvotwa Venezia Marechera, and some of his siblings, childhood friends, classmates and lecturers from the University of Rhodesia (now the University of Zimbabwe) and University of Oxford, fellow writers and poets, people and friends from London and Oxford and his publisher, James Currey, it is an exhaustive compendium of the writer’s life and work.

Although by the time it came out it was common knowledge in Harare’s literary circles that the two had been in a relationship, the biography didn’t hint at their intimacy and love triangle (involving Veit-Wild’s husband); it focused on the man and his work. In the introduction, she describes the writer as a “beloved friend”.

A portrait of Dambudzo Marechera from a series that produced the cover image of the posthumously published The Black Insider. (Photo courtesy of the Dambudzo Marechera Trust)

A portrait of Dambudzo Marechera from a series that produced the cover image of the posthumously published The Black Insider. (Photo courtesy of the Dambudzo Marechera Trust)

At home, in the eastern town of Rusape, where Charles William Marechera was born on 4 June 1952, he went as Tambu (short for Tambudzai). Later, shedding his Anglo-Saxon heritage, he became Dambudzo — the noun form of the Shona word for troubles. He was so named because, as family legend says, his mother carried him for 11 months. The already desperate poverty in the family was exacerbated by the early death of Marechera’s father in an accident.

The tragedy pushed the family from their council-owned house into a shanty town, and his mother into prostitution. For high school, Marechera managed to get into St Augustine’s, an Anglican Church-run school, where his facility across the arts — drama, painting and writing — was clear. At A levels, he achieved three distinctions and a generous scholarship to study for a BA honours in English at the University of Rhodesia.

He was then a drinker who spent a lot of his time at the students’ bar on the university campus. Although he still read widely, guided by his own instincts, Marechera neglected his work; consequently, his grades were lacklustre. Even then, it was clear Marechera was better read than any of his peers — his lecturers said he was by far the best African student they had ever had — and whenever he handed in assignments, his strong skills of analysis, originality and a creative mind were apparent.

Even in ordinary conversation, despite his speech impediment, his evident pleasure in words was palpable. He was some kind of an alchemist, oxidising words created in a different, colder context, to make sense of his own situation in the far, tropical reaches of the empire.

On being expelled from university for participating in the student demonstrations of 1973, Marechera was awarded a scholarship to New College, Oxford. He arrived at Heathrow Airport with “neither money nor personal belongings”; when Iris Hayter, the wife of the warden of New College, received a call from airport authorities about a certain black Rhodesian who had just landed, she told them: “Put him into a taxi and send him here.” It was the beginning of a difficult relationship with the institution, which saw him sent down the following year.

His expulsion from Oxford was an enduring source of the writer’s legend, a self-mythology from which Marechera derived joy. Two theories surround his expulsion from Oxford, the one being that he set fire to university buildings; the other that he was given a choice between accepting psychiatric help or leaving the university: “I had to invite them to expel me.”

Marechera’s stay at New College was troubled: drunken, obnoxious behaviour, borrowing money without returning it, and accumulating debts at the local bookstore. “The final major crisis occurred in early 1976 when he assaulted students and members of the domestic staff, threatened to murder named people and to set the college on fire (he started one small fire); he was also arrested and fined by the police one night for being drunk and disorderly.”

When the college authorities offered him the choice of a treatment or expulsion, he agreed to see the psychiatrists at the local Warneford Mental Hospital, where the doctors concluded that he was “not mentally ill”, instead suggesting counselling. He did not take up the offer. After another outbreak of violent behaviour and a missed tutorial, he was expelled on 15 March 1976.

Charles Mungoshi and Dambudzo Marechera in Harare, June, 1987. (Photo: Ernst Schade)

Charles Mungoshi and Dambudzo Marechera in Harare, June, 1987. (Photo: Ernst Schade)

There is little doubt that these bouts of drunken unruliness, truancy from class and lack of application in his studies, were made worse by his stay in the forbidding and alienating ambience of Oxford — he was one of two black students who enrolled that year at New College.

But some of the strange, anti-social behaviour was already apparent in Rhodesia. A family secret related to Veit-Wild by Marechera’s brother, Michael, might help to explain Marechera’s tragic trajectory.

In the legend, from 1850, a great-grandmother accused of being a witch was taken to the forest and tied to a tree. However her end would come — starvation in the wild or being torn apart by predators — her fate was sealed. Her spirit had apparently wandered in those forests until a century later.

Towards 1969, Marechera’s mother, a descendant of the “witch”, lost her mind. It appears the spirit of the “witch”, which wanted Marechera’s mother as its host, was visiting illness on her to force her into a covenant.

When she consulted a traditional healer, n’anga, she was told she could get rid of the mental illness only by passing it on to one of her own. “She did not choose Lovemore [the eldest], because he was her favourite. She did not choose me because I was named after a powerful ancestor whose spirit would protect me from such things. She chose Dambudzo.”

In 1972, when Marechera was sitting for his A levels, he began to suffer delusions. “He was sure two men were following him everywhere. [Yet] only he could see them.” He managed to sit for his exams by taking “many tranquillisers”. Father Keble Prosser, St Augustine’s headmaster, said that Marechera “showed a number of signs of clinical mental illness, including hearing voices threatening him”.

“Subsequently, I felt he must have known what mother had done. When later he left for England my bones told me he was running away from something,” Michael said, summing up what, if true, was a sordid instance of Shona metaphysics.

“When he returned to Zimbabwe he refused to see mother — I now understand why. It is difficult to explain such matters to those who do not know our culture. But I feel this story explains why Dambudzo always said he had no family and why he saw himself as an outcast.”

Marechera, pictured at a lunchtime reading on First Street, Harare, in 1983, is a lodestar for a younger generation of Zimbabwe’s writers, even those born after he died in 1987. (Photo: Flora Veit-Wild)

Marechera, pictured at a lunchtime reading on First Street, Harare, in 1983, is a lodestar for a younger generation of Zimbabwe’s writers, even those born after he died in 1987. (Photo: Flora Veit-Wild)Expelled from Oxford, Marechera began the next episode of his life in despair, a “homeless wanderer”. What became The House of Hunger was written, in Marechera’s own account, in a tent by the River Isis, Oxford, in the kitchen of Stanley Nyamfukudza — his compatriot enrolled at Oxford, and a future writer himself — and in the home of other friends. Just less than a year after Oxford, he sent a collection of the short stories (then with the title At the Head of the Stream) to James Currey, publisher of Heinemann’s imprint, the African Writer Series.

He wrote back immediately to say he was “most impressed” by the collection. Even before the formal acceptance of the manuscript, Currey sent Marechera an advance of £150.

Currey’s enthusiasm for the work was shared by external reviewers of the manuscript; one wrote: “It’s as terrible a book as it sounds, raw and very powerful. I don’t know another book about Africa that deals with the whole situation at such a level, except perhaps [Doris] Lessing or [Bessie] Head …”

On its publication in December 1978, Lessing herself wrote of “the book [as] an explosion”, an aptly ironic description of the ceremony for the Guardian Fiction prize, which Marechera shared with the Irish writer Neil Jordan. It was a fiasco. Marechera hurled china at the chandeliers, shouted at the attendees and was a nuisance.

For the US edition of the book, Lessing wrote the blurb: “If this is his first book, what may we not hope for from his next …” Yet The House of Hunger was, in popular appeal, realisation and critical acclaim, his summit — an achievement he would neither replicate nor surpass.

The next manuscript, published as Black Sunlight (1980), was accepted more in the hope that it would encourage him to write a “proper” novel. But the novel Currey hoped for never came. Currey complained to Veit-Wild that Marechera used to send him unrevised manuscripts: “Each one looked as though he’d blasted it out on the typewriter. It was always a cluster of fireworks; there was always exceptional material there.”

When Currey received readers’ reports that suggested changes, Marechera was unable or unwilling to make them. “This was the problem. It seemed to me he had far more brilliance and exceptional talent than practically anybody else, but he needed to move on from this sort of amateur brilliance to learn the craftsmanship of holding an audience.”

In Harare, where he returned in 1982 for the adaptation of The House of Hunger by the South African-born British filmmaker Chris Austin, he found it difficult to get published. Mindblast was published after it was first rejected by Zimbabwean Publishing House, which held the local rights of The House of Hunger. It was the last book to be published in his lifetime. The work — comprising plays, diaries and poetry — shows that brilliant mind, but it is uneven in quality.

Flora Veit-Wild and Dambudzo Marechera in her family garden in Highlands, Harare, 1985. (Photo: Lourdes Mugica Arruti)

Flora Veit-Wild and Dambudzo Marechera in her family garden in Highlands, Harare, 1985. (Photo: Lourdes Mugica Arruti)

The publishers’ rejection slips, which Marechera ascribed to censoring hands, were a source of his anguish. “While he was disgruntled by the publishers’ ignorance and their failure to appreciate his style of writing,” Veit-Wild writes in her memoir, “he also wondered whether he was capable of producing a literary work with the scope and energy of his previous books”.

In August 1987, Marechera’s friends found him ill in his flat; he was emaciated and had only one, partially functioning lung. In the early hours of 18 August 1987, he lost consciousness and never awoke. He was only 35, a victim of Aids-related pneumonia. “In a way he was too old to live and too young to die,” was the verdict of the Zimbabwean filmmaker Simon Bright, who knew Marechera from London.

The Dambudzo Marechera Trust, consisting of the writer’s brother Michael, the South African poet Hugh Lewin, and Veit-Wild, was set up. The trust published the novel The Black Insider (1990); a poetry collection, Cemetery of Mind (1992); and Scrapiron Blues (1994), a compilation of his poetry, children’s stories and journals — one of Wole Soyinka’s books of the year in 1996. The posthumous books were all compiled and edited by Veit-Wild.

At the height of the cult of Marechera, Zimbabwe was sometimes conflated with its most famous writer. “I am honoured to be in Harare, Zimbabwe, the land of Dambudzo Marechera,” the Ugandan writer Taban Lo Liyong said, during the Zimbabwe International Book Fair in Harare in 1991. What these well-meaning, laudatory outbursts may occlude is something more revolutionary and far reaching that Marechera achieved: that is, to lay the foundation of a whole new literature, in both Shona and English.

Many young, aspiring writers visited him in Africa Unity Square, a park in the centre of Harare’s central business district, where the vagabond poet typed away in his open-air, makeshift office.

Africa Unity Square, where these youths went to meet Marechera, clutching their manuscripts and notebooks — consulting him about publishing while paying no heed to the slander and disregarding the almost universal suspicion with which he was viewed by the literary and political establishment — is the real headquarters of Zimbabwe’s postcolonial literary tradition.

Some of these people include Robert Muponde, now a Zimbabwean literary scholar based at the University of the Witwatersrand, and the author of the recently published childhood memoir, The Scandalous Times of a Book Louse (2021). Muponde is said to have learnt to type on Marechera’s typewriter. Then there is Charles Samupindi, the late author of the intense tragic novel Pawns (1990), the forgotten book about the betrayal of guerrillas of the 1970s struggle for Zimbabwe’s freedom. I am not sure if the writer Phillip Zhuwao, who also died young when he had begun making a mark in South Africa’s literary circles, met Marechera, but the influence of the older writer on his work is clear.

When Dambudzo Marechera: A Source Book on his Life and Work, Scrapiron Blues and Cemetery of Mind came out, I was in high school. When the school librarian ordered these books, I and a few other friends borrowed and read them with reverence and diligence. It was impossible to think that this boy — this erudite writer who had gone to Oxford where he tried to burn down a library — was our countryman.

By then the Mugabe dictatorship was well established and, with the surrender of the founding nationalist Joshua Nkomo to save his fellow Ndebele-speaking supporters from the Gukurahundi genocide by joining Zanu-PF, no sigh of protest could be heard in the land.

Marechera inside his Harare apartment. (Photo: Ernst Schade)

Marechera inside his Harare apartment. (Photo: Ernst Schade)

For this reason, Marechera’s dissident voice — this phrase is used flippantly these days — was prophetic. Apart from Marechera himself, we attempted to read all he had read and so, in many ways, Marechera was an alternative curriculum, one that digressed from nationalist imperatives and platitudes, and the examination-oriented demands of the Victorian-light syllabus then foisted on us.

Even some of the nicknames we appended to ourselves from those years were unapologetically literary; one friend — who tragically died young, and who discovered Fyodor Dostoyevsky through Marechera — went as Dostoyevsky.

These were monikers my high-school English teacher, Kudzai Ngara, now a literature professor at the University of the Free State, queried at the time. Did we realise what heavy burdens we were taking on ourselves? he asked. But we were naive, as one is when 16, and thought we could take on the burden — curse, even, now that I think of it — of literature.

Yet Ngara wasn’t just a check on my literary delusions, but my biggest enabler. He loaned me from his own collection some of the novels that were not in the school library. This is how I came to read the US writers James Baldwin and Richard Wright, the Nigerian Wole Soyinka, the Ugandan Okot p’ Bitek and many others. Once, while returning his copy of Song of Lawino and Song of Ocol, I remarked that the Ugandan was “easy reading”; he gave me an important lesson on Africa’s oral tradition, observing that the kind of simplicity p’Bitek conjured in those stories doesn’t come easy.

In 2012, one of my editors at the Mail & Guardian, where I was arts writer, asked me to edit for length a piece about Marechera that Veit-Wild had originally written for Wasafiri.

She had often been asked, she began, why she hadn’t written a proper Marechera biography instead of the documentary biography; her answer — “that I did not want to collapse his multi-faceted personality into one authoritative narrative, but rather let the diverse voices speak for themselves” — was not the whole truth. She really couldn’t write his life story without including hers.

Born in 1949, she came of age in the student upheavals of 1968, when she enrolled at the Freie Universität Berlin, the epicentre of the protest movement. Like many others of her generation, she was asking questions about Germany’s Nazi past, in which millions of Jews were murdered. It was in the strikes of 1968 that she met her future husband, Victor Wild, one of the leaders of the protest movement.

Wild was a conscientious man who read widely on how Europe had underdeveloped Africa, colonialism, and what happens after the end of the colony. When Mugabe visited Essen in 1976 as a guerrilla leader, Wild was there and had a picture taken with him.

In trying to answer some of these questions — how the dominance of the centre over the periphery could be undercut — Victor and Veit-Wild decided to move to Zimbabwe. A toolmaker by profession, Wild got a job as a technical instructor at a trainee centre for a Harare company.

Marechera reading at the Zimbabwe International Book Fair in 1983. (Photo: Flora Veit-Wild )

Marechera reading at the Zimbabwe International Book Fair in 1983. (Photo: Flora Veit-Wild )

It was at the inaugural Zimbabwe International Book Fair, in 1983, that Veit-Wild first noticed Marechera. The next time was at a lunchtime reading in Harare’s central business district, where Marechera was in the company of his girlfriend: a certain Olga, a German woman teaching in rural Zimbabwe.

Veit-Wild and Marechera’s first proper encounter was “on a hot October” or when “Harare [is] in heat”, as Marechera would say. October, the hottest month of the year in Zimbabwe, is historically when most suicides take place.

Veit-Wild had gone to chat to the writer Charles Mungoshi about Zimbabwean literature at his offices in the Avenues, on the northern edges of Harare’s central business district. Marechera happened to be in Mungoshi’s office at the Zimbabwe Publishing House where he worked as an editor. Marechera sometimes went there to freshen up (some of these offices still retained the showers and baths used by their previous occupants) and warm up after nights spent under Harare’s skies; his sonnets clearly not long enough to cover both his feet and head.

“What a gorgeous visitor you have, Charles … Please, young lady, sit down.” It was Marechera, who then offered her a vodka, which she declined. But they had drinks later that very night. “I felt good with him, though not infatuated … At times, he reminded me of a lurking animal.”

After a missed date, they finally met at a hotel on the outskirts of Harare where their sexual relationship began. In the morning, when she told him she had to go back home — to her husband and two children — Marechera burst out: “What? You want to leave me here stranded? Surrounded by dissidents!”

In the Gukurahundi genocidal war, the armed militants Mugabe’s North Korean army unit were ostensibly fighting were known in popular Zimbabwean discourse as dissidents. “Is this a trap? With whom are you plotting?” Marechera was paranoid, rightly so, as he was trailed and hounded by spies from the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO). “Go and tell your colleagues from the CIO where they can find me.”

Not long afterwards, Marechera called Veit-Wild and, using one of his favourite phrases — “How can I put it to you?” — proposed that she leave her husband, bring her two sons along, and marry him. She said no and the topic never arose again. Yet Marechera smarted at the power dynamics of the affair. “I was the one who allotted the time we could spend together. Dambudzo went along with it, but the grudge that I was the one in charge rankled.”

He was still living on the streets, and Veit-Wild suggested to her husband that Marechera move into the cottage on their suburban property in Highlands, northern Harare. The thinking was Marechera’s moving into a home with a proper bed, regular meals and space to write would do him good.

Wild “was very welcoming”; he liked Marechera as a person, and for his erudition. Veit-Wild was moving between the two beds: the marital bed in the big, colonial-style house and the tiny cottage meant for black domestic servants. For a while the unusual set-up — this transgressing of ancient taboos — held.

Forget sex across the race divide in a land in which former Rhodesian prime minister Ian Smith once vowed would never have majority rule, “not in a thousand years”, here was a woman taking on the polygamists at their own game (I doubt the word polyandry was known in Harare then).

Yet it was not just romance. Marechera, a brilliant critic and an avid reader of the luminaries of the category now known as global literature (he loved Salman Rushdie), was expanding Veit-Wild’s literary worldviews. “Without me being aware of it at the time, Dambudzo was helping me, a newcomer to Africa, a white woman from Europe, to find firm ground on the minefield of how I was to approach Africa, Africans, African literature.”

Veit-Wild realised that Marechera wasn’t well and suggested that he seek help: psychotherapy. He refused. “No, thank you. Leave me alone.” Yet he couldn’t survive without other people’s help: those who bought him drinks and cigarettes at Harare’s pubs, and sometimes gave him a roof.

After losing his portable typewriter, his old friend from Oxford, Stanley Nyamfukudza, replaced it; the poet and scholar Musa Zimunya opened up his office, where Marechera wrote. At the University of Zimbabwe, where he was a cult hero, students would sneak him into their halls of residence for a night or two. “He seemed to think that he was entitled to be cared for by others,” Veit-Wild observes, “‘I am a writer. The world owes me a living,’ was his tacit credo.”

When cohabitation with his lover and her husband proved disastrous — there was an incident in which cops became involved — Marechera moved out. Together with another friend, the Wilds started paying for his flat in Sloane Court, on Herbert Chitepo Avenue, in the Avenues area of Harare.

The very thing that Marechera scorned, middle-class comfort — a flat, regular income from a job, medical insurance — would have made him a better writer, giving him space to write and revise. But in Marechera’s thinking, middle-class comfort was equivalent to selling out. “They all have their jobs, you know, all my contemporaries from university, they are civil servants or university lecturers or editors — they are selling their souls.”

In Zimbabwe, criticism of Veit-Wild began in the mid 1990s, when she returned to Germany to take up a position as African literature professor at Humboldt University. If the tone of critique has changed, its substance remains the same: that, in her own words, “I had made money and reputation out of my affiliation with Marechera”.

The publication of They Called You Dambudzo is certain to reignite the generation-old debate of Veit-Wild’s role in Marechera’s life and work and the place of Europeans and the West in African literature and literary initiatives. The US scholar Marzia Milazzo’s searing review in the Mail & Guardian is an extreme example of this new combativeness.

In Zimbabwe itself, critique of Veit-Wild has come mainly from the scholar Tinashe Mushakavanhu, who argues that, although the German scholar and, by extension, the European academy, do a lot to keep Marechera alive and visible, “they also bury him amid a sequence of affective and theoretical presumptions that take away his black agency and participate in a process of forgetting him altogether. What we have is a carcass, remnants on which they built their version of the African writer infected by European philosophy and theory to a point where he has no identity and is unrecognisable as himself.”

Yet, in many ways, the most trenchant critique of Veit-Wild remains the one made in the mid-1990s by the poet and university lecturer Musa Zimunya. If his critique has the most heft, it is because his relationship with Marechera goes back to 1973, when the two were students at the University of Rhodesia.

In Zimunya’s critique, published as a two-part series in the now defunct Parade magazine in December 1995 and January 1996, he traced his differences with Veit-Wild to an interview the German scholar conducted with him for her first book, Patterns of Poetry in Zimbabwe.

“Flora had already arrived at a conclusion, she didn’t like my poetry because it was borrowing too heavily on the Shona tradition, and it mattered little that she did not understand that tradition.”

Veit-Wild’s attitude towards him, Zimunya wrote, was “condescending, presumptuous and downright insulting”, adding that Veit-Wild’s mission was “to purge Zimbabwean literature of its perceived primitive traditions and its historical content.”

Flora Veit-Wild’s memoir, They Called You Dambudzo, published by Jacana Media, “reignites the generation-old debate of Veit-Wild’s role in Marechera’s life.”

Flora Veit-Wild’s memoir, They Called You Dambudzo, published by Jacana Media, “reignites the generation-old debate of Veit-Wild’s role in Marechera’s life.”In They Called You Dambudzo, Veit-Wild half-concedes her adversary’s arguments: “… I can see that Zimunya had his points. I did not know anything about Shona tradition.” She also admits that, even though her literary knowledge was quite sparse, “I still dared ask very outright questions and did not withhold my own personal views and judgments.”

In his critique, Zimunya also threw up a philosophical conundrum: “My literary experience does not tell me that Dambudzo would be forgotten without Flora and the so-called trust,” Zimunya argued.

But would Marechera be as well known as he is today if the Dambudzo Marechera Trust hadn’t been set up to publish The Black Insider, Cemetery of Mind and Scrapiron Blues — half of Marechera’s oeuvre?

The fate of the late Charles Samupindi — the gifted author of Pawns and Death Throes, who died in 1993 — is instructive; Samupindi is virtually unknown outside of Zimbabwe’s literary circles and even in Zimbabwe his works are hard to come by.

Samupindi, Marechera’s own literary son, is, in effect, an orphan and lies buried in a metaphoric unmarked grave, with no name in the street. So desperate is Samupindi’s fate that he doesn’t have even a Wikipedia entry.

Samupindi’s lot is not an outlier. In Zimbabwe, there is no tradition of writing literary biographies, not even of celebrated writers. To my knowledge, there are none on the novelist

Yvonne Vera, Charles Mungoshi nor the poet Chenjerai Hove, now all late. To what extent, then, do we owe the visibility and nuanced understanding of Marechera to Veit-Wild’s Dambudzo Marechera: A Source Book on His Life and Work and the other posthumous works?

Somewhere in Zimunya’s heated critique, there was a salient point not fully explored: “As for me, I shall resist with every gram of my will anyone — white or black — who tries to convince me that I should shine the shoes of literary tourists.”

The term “literary tourist”, an interesting coinage, is at the heart of this unlikely trajectory. By chance, a young German woman, a neophyte of African literature, encountered an important personage in African literature and ended up as the authority. It’s an unusual arc, for tourists rarely take back home anything of value except trinkets and airport curio art. What made this possible?

One day, in 1988, Veit-Wild went to meet the recently appointed German ambassador to Zimbabwe with a request; she needed money to undertake editorial and biographical research on Marechera. “Do write a little proposal for me, make a list of what has to be undertaken and a budget of the costs you foresee,” the diplomat told her. “If it is not excessive, I might be able to help.” The ambassador had then convinced the German Foreign Office to give her a grant and a 33-month stipend.

The funds enabled her to travel to Britain, throughout Zimbabwe, and elsewhere interviewing people who had known Marechera. Would Zimunya or any other black Zimbabwean scholar have been able to just walk into the German embassy with this proposal and receive this money? I doubt it. And of this privilege, her identity as a white German woman residing and working in the former colonies, Veit-Wild isn’t sufficiently aware.

In the poem Identify the Identity Parade, Marechera hinted, obliquely, at the big struggle over his legacy:

I am the luggage no one will claim

The out-of-place turd all deny

Responsibility

The incredulous sneer all tuck away

Beneath bland smiles;

The loud fart all silently agree never

happened;

The sheer bad breath you politely confront

With mouthwashed platitudes: ‘After all, it’s

POETRY.’

I am the rat every cat secretly admires;

The cat every dog secretly fears;

The pervert every honest citizen surprises

In his own mirror: POET.

Marechera is akin to a big tree in the savannah, certainly not the jacaranda that lines the streets of his haunts in Harare’s Avenues area — trees imported by British settlers from Brazil; nor is he the musasa tree he writes of on the first page of The House of Hunger; Marechera is closer to the baobab itself, muti mukuru, the big tree, providing fruit to the weary traveller, bark to the healer, and a nest to the birds of the sky — some of them migratory stocks that have flown from northern climes.

Whether vendors of pirated fiction on Harare’s streets; scholars in Africa, Europe and elsewhere; writers and readers across the globe, Marechera will continue to nourish us for a long time to come.