Installation view of Requiem, from left: Paulus Fürst, Doctor Schnabel von Rom, Kleidung wider den Tod zu Rom (1656); Artist unrecorded, Lonely Soul Ex-Voto (19th century). Photo Graham De Lacy

Liminal Identities in the Global South, mounted at the Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation (JCAF), is an exhibition that deploys the notion of “in betweenness” in its framing. This exhibition is, in fact, the second offering of a trilogy; the inaugural exhibition, titled Contemporary Female Identities in the Global South, opened in 2020, with an emphasis on foregrounding significant works by selected female artists.

The last and third exhibition of this trilogy, set to open in 2022, aptly titled Modernist Female Identities in the Global South, will reflect on how cosmopolitan sensibilities and indigenous identities are represented in the works of three modernist women artists.

The current exhibition, with its observable emphasis on liminality, features an ensemble of renowned contemporary female artists in Jane Alexander, Lina Bo Bardi, Lygia Clark, Kamala Ibrahim Ishag, Kapwani Kiwanga, Ana Mendieta, Lygia Pape, Berni Searle and Sumayya Vally.

These artists and architects, as suggested by the title, are brought into conversation with each other through a curatorial endeavour that, seemingly, places importance on two notable threads: they are artists and practitioners located in and “speaking” from Global South — as do all three exhibitions in this trilogy — and their selected works appeal to facets of liminality.

Lygia Clark, Máscaras Sensoriais (Sensorial Masks) (1967, replicas 2021). © and courtesy Associação Cultural Lygia Clark. Photo Graham De Lacy

Lygia Clark, Máscaras Sensoriais (Sensorial Masks) (1967, replicas 2021). © and courtesy Associação Cultural Lygia Clark. Photo Graham De Lacy

In postcolonial discourse this notion of liminality is, by way of cultural theorist Homi Bhabha, closely linked to the concept of hybridity in how it refutes fixed identities and, instead, determines them as being continuous and ever-changing. This seems to be a factor that was considered in the curatorial formulation of the exhibition in thematically aligning it with the physical space itself.

The anthropological underpinnings of this concept are quite well known. It was Arnold van Gennep who, in his canonical treatise Rites of Passage (1909), laboured to define shifting social situations that see individuals and communities move from supposed states of infancy to states of maturity. When he studied the initiation rites of the Ndembu community of Zambia, he foregrounded three stages in which neophytes move from boyhood to manhood.

In the first stage, they sever ties with the larger community and become secluded from society. They then, in the second stage, endure a period of transformation and transition, one riddled with ambiguity, for they are no longer boys, but not yet men. And in the final stage, they become reincorporated into their community — no longer as boys but as men.

Van Gennep gave a rich elucidation of this process; his successor, Victor Turner, penned The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (1969) and enriched its complexity by paying particular attention to the middle phase of this rite of passage. Turner, following Van Gennep’s thinking, conceptualised the rites of passage as a process of separation, transition and incorporation, and was notably concerned with understanding the orientation of the transitory phase, known, of course, as the liminal phase.

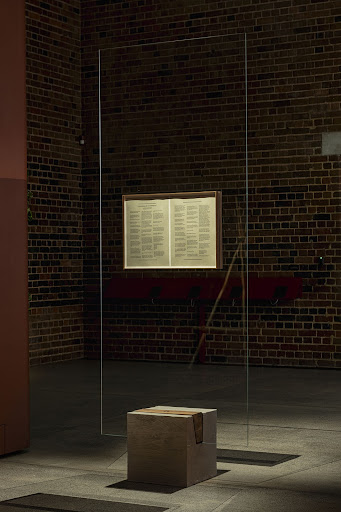

Installation view of Lina Bo Bardi, Glass Easel (1968), © and courtesy Instituto Bardi/Casa de Vidro; displaying Oswald de Andrade, Manifesto Antropófago (1928). Photo Graham De Lacy

Installation view of Lina Bo Bardi, Glass Easel (1968), © and courtesy Instituto Bardi/Casa de Vidro; displaying Oswald de Andrade, Manifesto Antropófago (1928). Photo Graham De Lacy

In this phase, in which the subject positions and social statuses are dissolved, relations of power become reconstituted anew. Turner suggests as much with his oft-cited maxim: “Liminal entities are neither here nor there; they are betwixt and between positions.” More importantly, however, Turner informs us that liminal situations also possess the potential to rearrange social structures by taking those deemed structurally inferior and elevating them to positions of authority, thus capacitating them with power.

Could this be the motivation behind choosing a select cohort of women artists from the Global South and arranging their works in a particular narrative in an effort to ultimately reaffirm their place in the modernist canon? This query becomes necessary in light of how at some point, indeed not so long ago, “liminality” became a trendy, catch-all buzz word in art speech, thinking and writing. It then becomes vital to understand what this term, which insinuates non-fixed identity, does for this exhibition, the foundation and its institutional profile.

The physical structure of the JCAF, located in a former electrical tram shed and substation that operated from the early 20th century until the early 1960s, is in itself a notable point of interest: one in which architecture meets heritage. It is a provincially listed, refurbished heritage site with a distinct modernist formalism that aptly captures the spirit of Mies van der Rohe’s architectural ethos: “Less is more.”

Certainly, the building speaks a language of simplicity with its apparent minimalist appeal that is partly achieved through making disparate materials work together: the original brick structure is used alongside customised glass and steel features that proffer a subtle contrast between tradition and innovation.

Installation view of Kapwani Kiwanga, Flowers for Africa: Nigeria (2014). Collection NOMAS Foundation, Rome, Italy. © Kapwani Kiwanga, ADAGP and DALRO. Photo: Graham De Lacy

Installation view of Kapwani Kiwanga, Flowers for Africa: Nigeria (2014). Collection NOMAS Foundation, Rome, Italy. © Kapwani Kiwanga, ADAGP and DALRO. Photo: Graham De Lacy

And yet, although its architecture is compelling in its subtlety, it is perhaps the punted hybrid character of this foundation — more pronounced in its institutional ethos — that is curious and warrants some scrutiny.

The foundation commissions academic research, functions as a technology laboratory and curates its own art exhibitions. Yet, despite these undertakings, it would seem as though it abjures being labelled as a traditional museum. This is tricky to comprehend, particularly when, for the purpose of sourcing artworks, the foundation is said to operate as a “museum-standard environment … that is, the antithesis of the white cube”.

The catalogue of this baronial space additionally stresses that, although its foundational imperative is advancing the appreciation of modern and contemporary art, the “JCAF is neither a museum nor a gallery. Rather, it is a new, ‘hybrid institution’, developed in the context of an emerging cultural economy to make a meaningful contribution to knowledge.”

Given that this avowal serendipitously evokes the notion of liminality that frames the current exhibition, one cannot help but find this remythification of the museum into “something else” as confounding in some sense. Put more directly: Are art foundations such as these completely different from the modern invention that is the museum? What is to be made of the paradoxical orientations of such cultural institutions that eschew identification with the conventional museum while, in many ways, adopting its ideological architecture, qualities, practices and nomenclatures?

Ana Mendieta, Untitled: Silueta Series, Mexico from Silueta Works in Mexico (1973-7 /1991). Colour photographs, framed. © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS) and DALRO

Ana Mendieta, Untitled: Silueta Series, Mexico from Silueta Works in Mexico (1973-7 /1991). Colour photographs, framed. © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS) and DALRO

Evading these questions only begs them even more, I find. And yet, these questions are also healthy problems, which have, in recent times, saturated the works of museum theoreticians such as Hesperia Iliadou-Suppiej, who oversaw the curation of the Malta National Pavilion at the Venice Art Biennale of 2019.

These are problems that underscore the vastly changing domain of terminology in museum practices. But for the JCAF, perhaps some reprieve can be found in the foundation’s strategic use of technology in forming its ambiguous identity.

The foundation uses digital technology to stimulate an immersive approach to its functioning: it is meant to foster an exploratory interface that encourages interaction with the knowledge and content of the various programmes in the foundation. This means that, through an app, one gets acquainted with a virtual universe prudent for curatorial and intellectual engagement.

Such technological innovation, as it appears, is meant to insert this foundation into the canon of a “future-orientated institution” — one that has, for instance, abandoned the old, traditional museological labelling system for one that enables participatory engagement through the app.

This approach intrigues me: not so much for the allusion to the efficacy of technology in a “museum-like” setting, but for what this implies about the orientation of this foundation, which is insistent on the particular framing of a hybrid institution.

Although implicit, what is of interest to me here, which should not be casually glossed over, is the presupposition that the use of this technology gives wholesome credence to the unique identity of this foundation as, shall we say, a “non-museum”? In other words, it seems as though there is a fabricated binary between the traditional museum, which still deploys traditional conventions, and the hybrid institution, obtains dynamism through its use of technology.

This binary may seem reductive but it does bring forth a broader inquiry: one becomes curious as to why the “museum” is, in the conventional sense, perceivably static, perpetually attendant to ethnographic practices of memorialising cultural artefacts and incapable of incorporating new technologies into its fold. One thus wonders if the application of the term “hybrid” to this foundation is not a semantic or conceptual reworking of something that already exists — like culture, something that naturally discards and adopts new instruments of functionality to ensure its survival.

And yet, there is something generative about this quandary: perhaps the specific framing of this foundation also presents an opportunity to evaluate its identity, relevance, directive and institutional ethos in South Africa’s art museum ecosystem, which has been enhanced by new institutions such as the Javett-UP, the Norval Foundation and the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa. There must be, surely, some form of critical reflection on these institutions and their purposes in relation to public museums.

These remain pertinent inquiries that cannot be exhausted in this exposition, but it is expedient, nonetheless, to appreciate the subtle, serendipitous manner in which the idea of hybridity pervades both the foundation and its current exhibition. Could it be, perhaps, that this saturation of hybridity in the foundation and exhibition presents or functions as a new or alternative genre of (re)presentation?

In fact, this exhibition has a few terminological focal points that theme identities in transition; in addition to hybridity and liminality, the notion of anthropophagia — a kind of cultural assimilation that is cannibalistic in its nature — is also foregrounded to draw attention to the ways in which Western cultures subordinate and feed on others for their survival.

Jane Alexander, Harbinger in correctional uniform (2006). Installation. Private collection. © Jane Alexander and DALRO. Photo Graham De Lacy

Jane Alexander, Harbinger in correctional uniform (2006). Installation. Private collection. © Jane Alexander and DALRO. Photo Graham De Lacy

The exhibition is mindfully divided into five parts: Prelude, Requiem, and Movements I, II and III. There is a sense that these parts, each bearing and conceptualised according to their own sonic tempos, were carefully demarcated in an effort to convey how the specificities dealt with by each artist in the show ultimately achieve a fragmented but wholesome narrative.

This curation completely repudiates the normative, cluttered, salon-like presentation of artworks. That minimalist temperament of Van der Rohe resurfaces once more in how the artworks are equally distributed in each segment of the exhibition — and overall, in the entire space.

The first part, Prelude, which features the works of Tarsila do Amaral, Oswald de Andrade and Lina Bo Bardi, zones in pointedly on the notion of anthropophagia, highlighting how iconic works from Latin America, such as do Amaral’s Abaporu (1928), have interrogated the hybridisations unfolding when European influences subsume local indigenous Brazilian traditions.

The second part of the exhibition, Requiem, concerns itself with highlighting the state of limbo amid the “event”, which, as philosopher Slavoj Žižek would have it, surmises a monumental happening that radically alters our perception of the world — the rupture of normality.

Here, the idea of the “pandemic” is scrutinised. This part reflects on some of the epoch-defining pandemics throughout history, such as the bubonic plague, the Spanish flu and, of course, the recent Covid-19 pandemic; it looks at the eventness of these pandemics and asserts how mankind is, one might think, engrossed in an indeterminate liminal space in which normality has dissolved and is yet to resurface.

Sumayya Vally/Counterspace, After Image (2021). Tinted mirror, steel. © and courtesy Sumayya Vally/Counterspace. Photo Graham De Lacy

Sumayya Vally/Counterspace, After Image (2021). Tinted mirror, steel. © and courtesy Sumayya Vally/Counterspace. Photo Graham De Lacy

This theme of the pandemic is extended to the third part, Movement I. In this segment, in which sculptures, prints and video pieces by Jane Alexander, Lygia Pape, and Lygia Clarke sit, attention is cast to the sensorial; these works theme the onslaught that this current Covid-19 pandemic has on our bodily senses and, in fact, the utility of these senses in a context that (often) enforces social isolation. The masks and leather overalls allude to this. In their overall narrative, they also allude to death, which forms the crux of the fourth part, Movement II.

This segment of the exhibition unfolds with a searing truth: our lives are temporary. In reflecting on the precarious nature of life, the works of Ana Mendieta, Kapwani Kiwanga and Kamala Ibrahim Ishag are contrived into a narrative about the impermanence of things and, indeed, the liminality of these things. Here, in this segment of the exhibition, images of female bodies in space and women performing rituals abound, but the piece that captivates the viewer is of Kiwanga’s flowers, which, aside from dealing with “institutional constructions of memory and the immateriality of symbols” remind the viewer of the transience of life.

This echoes well with what is presented in Movement III, the final segment of the exhibition, which closes this layered narrative with a profound sentiment that in the midst of the affliction and disasters that plague the world and reduce us to unspeakable depths of helplessness, there arises an opportunity to attain a radical vulnerability and a need for grace.

And yet, this segment is also not free of heavy content. Berni Searle’s and Sumayya Vally’s Counterspace’s works saturate this section of the exhibition. Searle’s impressive installation, made up of elephant bones, is a historical tracing of the desecrating of natural resources and atrocities committed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the turn of the 20th century.

The insistence on retelling the colonial violence that occasioned King Leopold II’s rule, which was enamoured with the pillaging of resources such as ivory, gold, rubber and other minerals, is not futile, for it offers an opportunity to think about the legacies of colonialism and its afterlives. Vally’s installation does an equally diligent job of retelling a historical issue: the exploitation of natural resources in Johannesburg. In studying this city’s mining history, Vally’s work, an undertaking concerned with the spatial politics of Johannesburg, brings up for closer examination how the (political) empire incessantly extracts from the earth and those who work it.

There is something laudable about how the curation of this exhibition organises these disparate yet well assembled movements to represent different states of in-betweenness. One might also appreciate the sense of slowness the exhibition inspires, in that the deliberate choice of artists, the deliberate numbers of artworks on display and the actual works in themselves demand that the viewer engage with them slowly and for as long as possible.

I suspect this partly informs why the exhibitions hosted by the JCAF have a durational nature: they typically run for extended periods of time in order to, on the one hand, allow for audiences to engage with them recurrently and on the other, to allow the themes of the exhibition to reverberate with the changing cultural and political situations of the day.

Although yet to fully settle into South Africa’s art ecosystem, the JCAF is an institution with immense potential and ought to be studied as a repository of the many cultures it memorialises through its exhibitions.