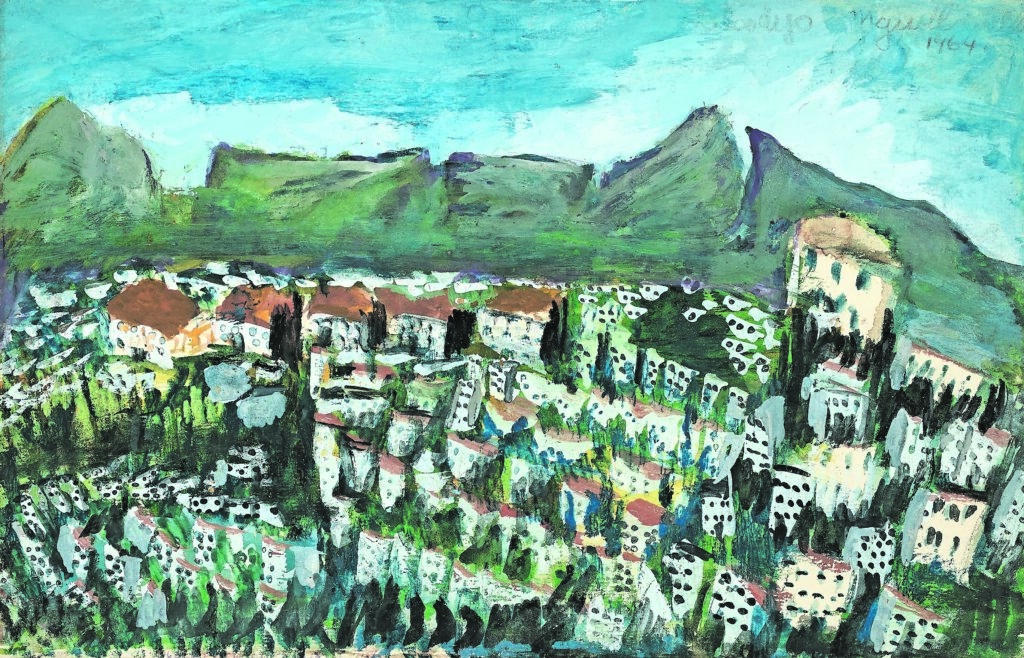

Broad brushstrokes: (from left) Gladys Mgudlandlu, Houses in the Hills, c1960s, Iziko South African National Gallery; Suburb (with Table Mountain), 1964, Homestead Collection.

‘You may see no rivers on the ground, but we keep the rivers inside of us … Sometimes we see the rain clouds gather even though not a cloud appears in the sky … There was always something on this Earth man was forced to love and worship by reason of its absence.” — Bessie Head.

The recently opened exhibition, When Rain Clouds Gather: Black South African Women Artists, 1940-2000, at the Norval Foundation, Cape Town, named after exiled writer and anti-apartheid activist Bessie Head’s first novel, provides a humble historical survey and catalogue of diverse Black women’s artistic practices, stretching as far back as the 1940s.

It would be remiss of me to not point out the unprecedented nature of such an exhibition, given that the field of art history has traditionally — deliberately and/or by systematic obfuscation — had the world believe that such a rich and enduring creative practice does not exist.

Broad brushstrokes: (from left) Gladys Mgudlandlu, Houses in the Hills, c1960s, Iziko South African National Gallery; Suburb (with Table Mountain), 1964, Homestead Collection.

Broad brushstrokes: (from left) Gladys Mgudlandlu, Houses in the Hills, c1960s, Iziko South African National Gallery; Suburb (with Table Mountain), 1964, Homestead Collection.

Walking through the show, one can’t miss the palpable corrective of prevailing injustice — political and discursive — and the pressure such bigotry has put on Black South African women in visual art who, even now, need to provide proof of their existence in the field.

The show is curated by Nontobeko Ntombela and Portia Malatjie, two Black feminist art historians who, in a period spanning more than a decade, have independently dedicated their research to the study of Black women artists in South Africa and have spent the past five years putting together this project.

When Rain Clouds Gather is a timely exhibition, because it is increasingly becoming clear that South African art history needs to be decolonised and exorcised — at all levels and in its entirety — of all remnants of imperialist oppression.

Typically, however, the renewed emphasis of the decolonisation agenda focuses on the reputation of the discipline, particularly its cold treatment of non-Western people’s cultural practices: what art critic Charles Gaines once described as “a theatre of refusal”.

Gaines’s notion spoke specifically about how these “strategies of marginalisation … punish the work of Black artists by making it immune to history and immunising history against it.” In other words, what does not meaningfully register, entertain, and justify the assumptions of this his-story of art, is discriminated against.

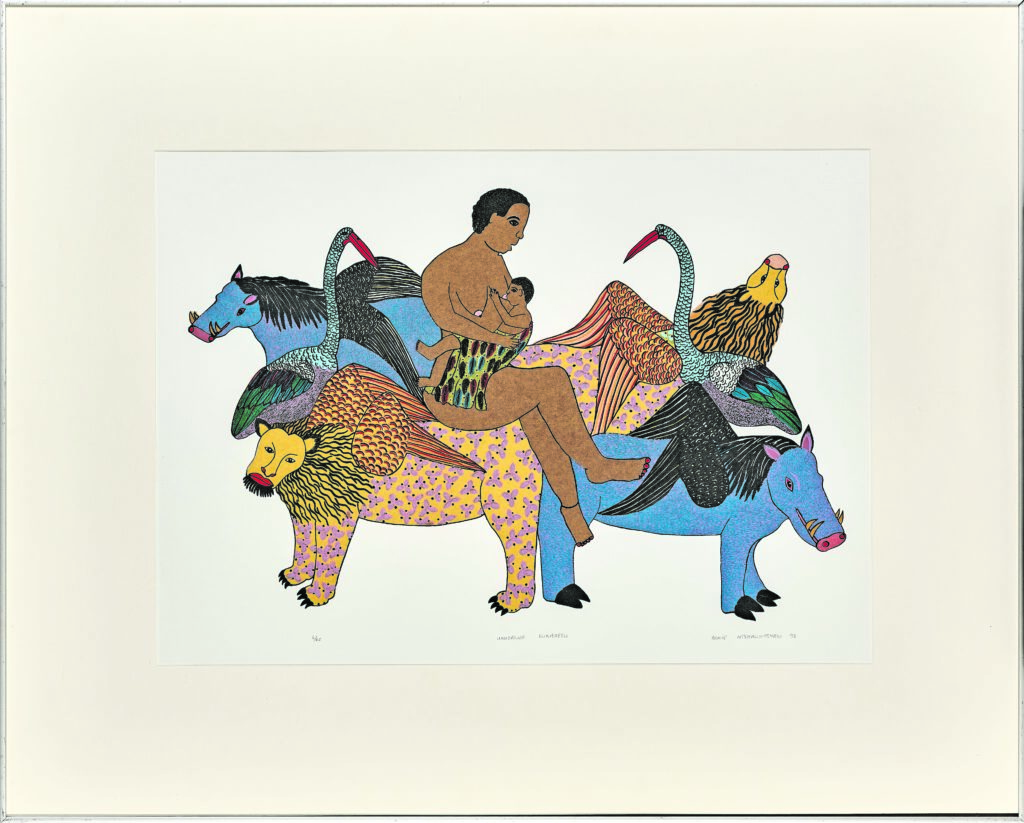

Figures and symbols: Henriette Ngako, Forefather Spirits, 1996, University of Pretoria Museums Collection.

Figures and symbols: Henriette Ngako, Forefather Spirits, 1996, University of Pretoria Museums Collection.

Of course, there’s always been some tittle-tattle about the existence of Black women artists in South African art, who often seemed to score cursory mentions here and there — either as mere addendums or afterthoughts in what usually are blockbuster shows or publications centring their Black male and white female counterparts.

The rooms invented for Black women artists in our official culture are supposedly “theirs”, but are ironically invented and administered by others on their behalf.

Historically located in these marginalised enclaves, Black women’s art had unofficially been relegated — often without acknowledgment — to the position of the auxiliary product that operates as a stand-in, a supporting act or a crude pornotropic summary, unrepresentable in the official culture.

When Rain Clouds Gather is as much about critiquing that historical offence as it is about celebrating the surviving, the existing, and the creating of and by Black women artists, despite and because of it.

In other words, it asks us to contend with, as well as contest, the histories (of art) that have restrained, or even “tippexed” out the ways in which Black women artists have continued to create under such climates.

Figures and symbols: Dinah Molefe, Traditional Figure, African Woman, c1970s, Campbell Collections, University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Figures and symbols: Dinah Molefe, Traditional Figure, African Woman, c1970s, Campbell Collections, University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Head’s use of the weather in her novels not only forms part of a “drought-resistant literature” to quote Isabel Hofmeyr, but also uses these motifs to enable “a disquisition on the universality of prejudice” according to Christina Sharpe.

And because we cannot escape the weather — at least not fully — perhaps as we cannot escape anti-Blackness, this climatological inference provides certain clues to how Black women artists have weathered the storms.

Thus, the presence of Bongi Dhlomo’s painting, titled Artist Unknown, which interrogates the ethnographic script that undergirds the habits of the Western art market’s acquisition, exhibition, and representing of traditional African artefacts also speaks to the framing hand of the art historian.

When Rain Clouds Gather is the first exhibition of its kind, almost 30 years after the “end” of apartheid. The show brings together Black women artists who exemplify South African artistic sensibilities before the emergence of the contemporary scene, represented from across a range of media: painting, sculpture, photography, printmaking, tapestries, pottery and so on.

Beyond that, the exhibition also creates an interesting dialogue between the 40-plus artists and across their differently classified and ranked mediums — modern versus traditional; art versus craft — of more than 150 artworks, spanning from the 1940s until the year 2000.

In the first instance, art mediums and materials associated with Black women’s art aren’t arbitrary tools, but modes of assigning, differentiating and classifying according to established race and gender hierarchies that pervade the dominant order.

These superficial differences were/are maintained as modalities of domination and of keeping Black people (in general) in a state of aspirant inferiority; “labelled, checked, relabelled, and rechecked in a process that would seem to have no end” to quote artist Bongi Dhlomo.

However, it isn’t just the dialogue that makes this exhibition exceptional, but rather, to borrow from the classical feminist expression of women’s autonomy; it is that, this time around, Black women artists literally have the room to themselves — curated and conceptualised by themselves.

Consequently, this intramural dialogue — in perfect juxtaposition — also unravels the idiosyncratic ways in which Black women artists complement the last century concerns on the development of vernacular modernisms.

Artists like Bonnie Ntshalintshali are the furthest thing from “naive and functional”; so too Noria Mabasa or Helen Sebidi’s interstitial lingerings between the realms of reality and dream, Western and indigenous forms do not indexicalise a “transitioning” aesthetic.

At best, these artists and many like them, do not necessarily suggest liminality as per the script, but rather an artistic dis-imbrication. In other words, they are neither evolving into prescribed ends nor slipping back into untainted pasts — instead they have enabled novel forms of properly modernist expression that have reconfigured both their own cultures and the ones imposed on them.

Thus, irrespective of their standing in the cultural hierarchy of recognition — whether known or unknown — the show joins Gladys Mgudlandlu, Helen Sebidi, Noria Mabasa, Bongi Dhlomo-Moutloa, Bonnie Ntshalintshali and Sophie Peters shoulder to shoulder with Valerie Desmore, Ruth Motau, Dorothy Zihlangu, Henriette Ngcobo and more.

Those it has, for various practical and pragmatic reasons, excluded in this voluminous display — we find them not only acknowledged and remembered in a long, comprehensive inventory, but also related to other extra-cultural situations in ways that typify not so much a “fragile” but counterpublic archive.

The Political, Love | Pleasure | Intimacy, Landscapes, Wrestling Traumas, Spiritual and Religious Conjurings are some of the themes the works are grouped in.

I personally found the conspicuous absence of labour and domesticity as themes quite refreshing, considering that their function tended to serve particular agendas. “The politics of the domestic removes Black women from formal politics, relegating them to the position of the supporter and caregiver, rather than instigator and leader” reads a wall text.

This is certainly not to say that domestic and labour issues are excluded in the show, more so if we consider Ruth Motau’s elegant photograph, titled A Woman Relaxing at the Alexander Woman’s Hostel (1991), which shows a half-naked, bare-breasted Black woman reclining on her bed, probably after a long day at work. Apparently, Motau had kept this particular image hidden away, because she wasn’t sure how the public would respond to it.

Indeed, especially when we consider how former arts and culture minister Lulu Xingwana walked out of photographer Zanele Muholi’s show, in 2009 after she saw photographs of naked Black women, one doubts Motau would have fared better in 1991.

Splash of Colour: Bongi Kasiki, Blue Bird, 1993, University of Pretoria Museums Collection.

Splash of Colour: Bongi Kasiki, Blue Bird, 1993, University of Pretoria Museums Collection.

For a show virtually without precedent in South African art, contradictions are unavoidable. One such contradiction begins with the underlying and much deserved corrective of the white liberal art establishment’s fascination with “firsts”. By attempting to remedy the problem of “firsts” in art history, the show includes Valerie Desmore’s early paintings from the 1940s to disrupt the narrative coherence that from 1961 on, hailed Mgudlandlu as the first Black woman to have an exhibition. This, of course, is something Mgudlandlu herself had allegedly believed and even celebrated.

But important as this corrective might be in terms of disrupting white condescension, it is also hard to bypass its own historically shaky critical premise. Although it is important to recognise Desmore — a mixed-race artist of white and coloured parentage — as a precursor to Mgudlandlu, this premise is methodologically awkward, considering its retrospective use of “Black”.

In other words, “Black” as an inclusive configuration in South African political lingua franca is specific to the 1970s context — some serious years after Mgudlandlu’s emergence and certainly decades after Desmore’s time, in which coloured and Indian communities had yet to “embrace” Blackness. This particular detail might have to be rethought, more so if it’s going to be foregrounded as an instance of historical accuracy.However, When Rain Clouds Gather: Black South African Women Artists, 1940-2000, is an exhibition that is opening up a new and often untold history of our rich and troubled art histories.