We are living in a time of great narcissism. From attention-seeking politicians and celebrities, to digital oversharing on social media, this inflated sense of self – and the individualism that underpins it – has contributed to some of the greatest challenges of our times: the destruction of our planet, inequalities and divisions, and the decline of communities and communal ideologies.

Ebrahim Ebrahim’s memoir, Beyond Fear: Reflections of a Freedom Fighter, is a powerful antidote to any feelings of despair. Ebrahim, or Ebie as he was known, reminds us that there are other ways to live our lives, in the service of ideas and ideals.

Beyond Fear provides a gripping yet poignant personal account of many of the events and ideas during South Africa’s struggle for freedom. Through his role in the ANC’s sabotage campaigns of the 1960s and his imprisonment on Robben Island in 1963, we gain an intimate insight into the early days of the struggle. After his release from jail in 1979, Ebie became the head of the ANC’s Political Military Committee in Swaziland.

The power of the book lies in its vivid account of the inner life of someone who shaped the struggle for freedom, democracy and justice in South Africa. Even when dealing with questions of life and death, courage and betrayal, the book evokes warmth and humour. Some of the most seemingly innocuous observations turn out to be the most revealing. The book succeeds in conveying humanity at its best and at its worst. Ebie has written an honest, intensely human book.

At its core, the book offers an additional valuable perspective for those who are already familiar with South Africa’s struggle history. For people who are less familiar with SA’s history, the book is an excellent introduction because it provides an accessible and engaging narrative of the evolution of the ANC.

Three aspects of this narrative are particularly striking.

Ebrahim and his wife ShannonFirst, the book illustrates the stark contrast between the early days of the sabotage campaigns in the 1960s, and the much more professionalised structures of the ANC later. After the South African government declared a State of Emergency in 1960, Ebie recounts discussions amongst comrades about the use of violence and recruitment. None of them had any training in bomb-making or the handling of explosives. Ebie’s earliest acts of sabotage are remarkably amateurish, as he describes the haphazard handling of dynamite and the use of chilli powder to ward off police dogs. When he is released from jail in 1979, the movement is much more organised and professionalised. In Angola, he was taught to handle bazookas and AK-47s, and he notes that ‘this was a far cry from my early days as a saboteur’.

Second, the book highlights the importance of social bonds and social networks in shaping the struggle. Beyond Fear vividly highlights the importance of solidarity and personal connections. Early on, he remarks that ‘my comrades were like family’. Ebie describes the social relations on Robben Island, the attempt by the authorities to divide, but the intuitive resistance on behalf of the prisoners to unite and share. Day-to-day life on the island involved camaraderie and friendship, and the book describes lighter moments such as catching and eating crayfish or saving penguins from oil slicks.

Finally, this memoir reminds us that ideas were at the heart of the struggle. Ebie and his comrades discussed how to oppose apartheid and its unjust laws, but also what kind of society might replace Apartheid SA. In the Defiance Campaign in the early 1950s, Ebie attended political classes to learn about colonial exploitation and common struggles. When he was in jail the first time, he describes political discussions with the other prisoners, on topics including the trade union movement and Stalin’s 1913 text ‘Marxism and the National Question’. These discussions would be held in the evenings, with the prisoners putting their mouth or their ear to the small peephole in their doors, depending on whether they were talking or listening. Some of the most interesting parts of the book describe the political education at the ‘University of Robben Island’. There were lectures on political theory, labour theory and other topics, followed by discussions among the prisoners at lunch time when working in the prison quarry, or in prison cells. Materials were sometimes smuggled into the prison, and eagerly read and discussed. Indeed, a common theme throughout the entire book is the constant dialogue and debate about political ideas and ideologies. Ultimately, Ebie’s own position on socialism and how and when this might be achieved is left unresolved. “I have grappled with this my whole life,” he says.

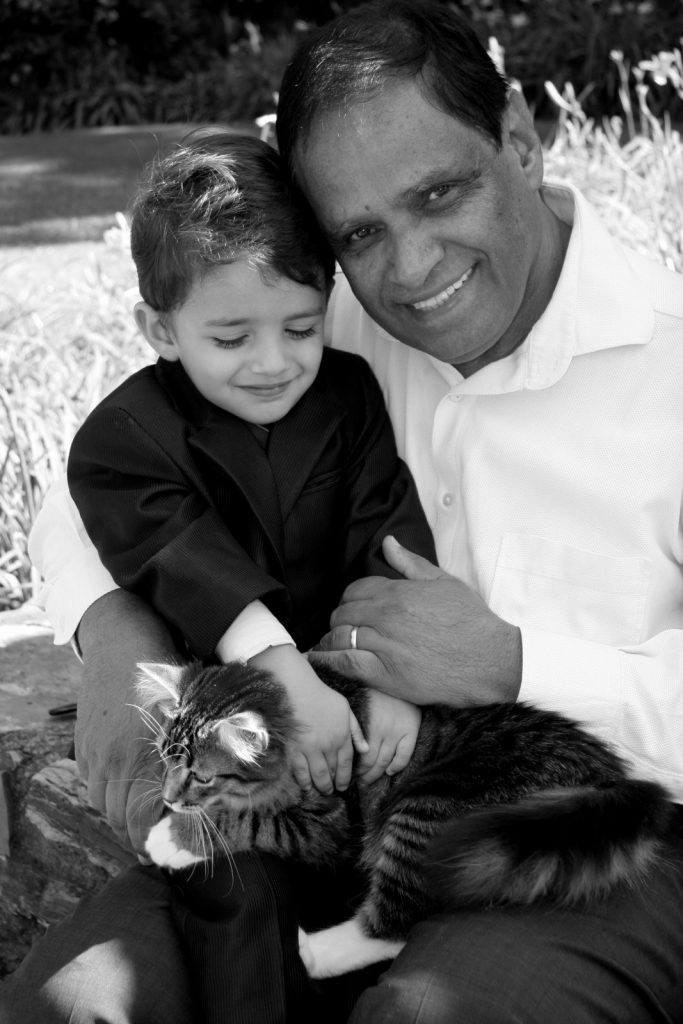

Ebrahim and his son Kadin in 2010And finally, Beyond Fear covers Ebie’s life in post-apartheid South Africa, his role as Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, his involvement in conflict resolution initiatives around the world, and his enjoyment of a family life with his loving wife Shannon, his two young children Sarah and Kadin, and his elder daughter Cassia. The ability to enjoy ordinary moments of life is conveyed as an immense gift. Despite his diagnosis of lung cancer and his death at the age of 84 in December 2021, we sense the gratitude that shaped Ebie’s later years.

In his statement to court in 1987 he said, “There are countless others like us who are prepared to sacrifice their very lives to achieve the noble goal of the emancipation of our country. We shall achieve victory soon!”

Ebie’s unwavering commitment, his optimism and spirit will undoubtedly inspire a new generation of revolutionaries. Against the backdrop of today’s political and social climate, Beyond Fear restores faith in South Africa’s potential, and indeed the possibilities for a better world. It is a powerful reminder that our lives gain meaning when we believe in something bigger than ourselves.

Devon E A Curtis is an Associate Professor in Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge. She was a friend of Ebie’s and his family.