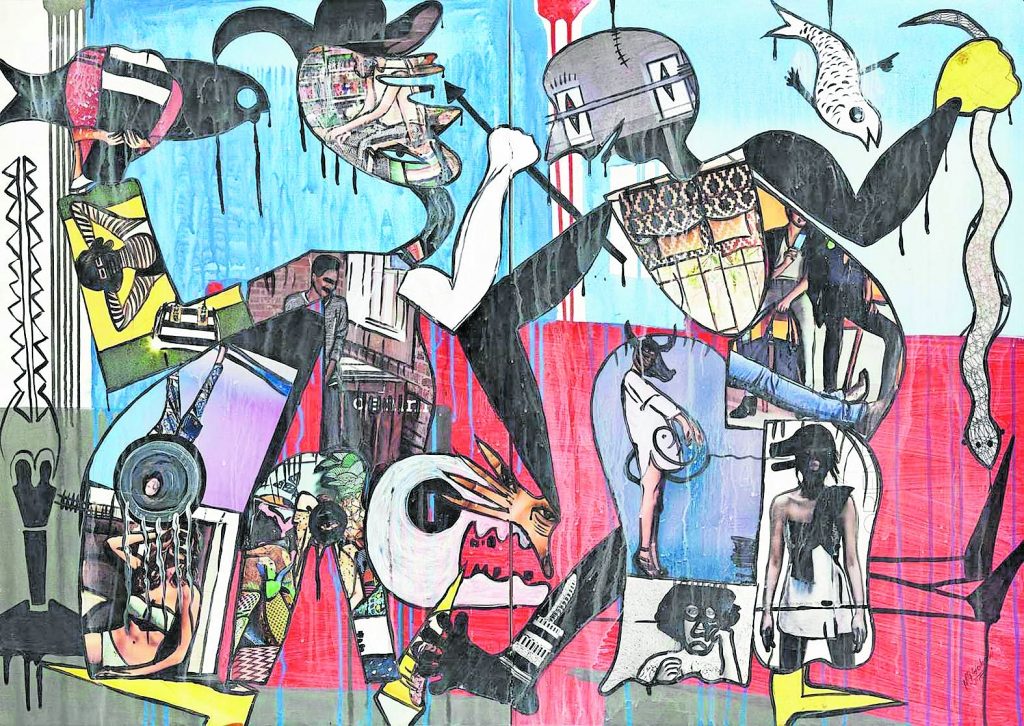

Talent: Frans Thoka uses oil on blanket in his work titled ‘Gowa ke go Tsoga’

At the end of the 1980s, art critic and historian Elza Miles wrote a scathing article titled “Kuns en die Groot Korporasies (Art and the Big Corporations)” in which she suggested that corporate art collections “result in nothing more than self-aggrandisement and self-promotion”, recalls Stefan Hundt, the curator of the Sanlam art collection.

The article set the Sanlam art advisory committee on a path that led to “a shift in consciousness … towards more contemporary artists and the realisation that there were serious gaps in the collection with regards to works by black artists”.

The widely held perception that the worlds of art and business do not make for good bedfellows is partially rooted in the idea that artistic expression has little place or relevance to big business, save for adding prestige and character to a reception area or meeting room.

Not only is corporate South Africa often credited with contributing to the growth of the art sector in the 1980s and 1990s but, since the advent of democracy, many corporates have focused on collecting and supporting emerging artists in a fairly holistic manner.

Some have used art to lend an air of civility to perhaps ruthless and sometimes unpalatable operations. The late mining magnate, Brett Kebble, and his titular art award scheme is one such example. To some degree, art dealers and artists have perpetuated this separation between art and business because it serves to underscore the idea that art is not a commercial product like any other.

Yet when you take a close look at how big corporates — particularly those focused on investments, commerce and banking — have absorbed art not only into their lobbies but through structured acquisition strategies and programmes to support artists, have sponsored art fairs and, importantly, conceive of the role of art, you can’t help but think art and commerce make the best of bedfellows.

This relationship has not been without pitfalls. Take the recent trend in art awards where the finalists’ works are offered at auction, leaving some artists with low or premature records that don’t always serve them in the long term. Or that banks are validating the value of the works they acquire through the awards system.

Social media about some of these awards and programmes supported by banks — run by marketing agencies with little knowledge of art — has often been to the detriment of the artists.

Award programmes are easy to unpick but it would be difficult to make a critical assessment of corporate collections. There are not lists of works available for scrutiny. These are private collections, even though they are regularly made public.

“Do corporates disclose what they’re actually purchasing? We haven’t. We’ve never really gone out to market to say this is what we are purchasing and this is how much we spend. You would only really notice what we’ve purchased if you walked around our offices and looked at what is hanging on our walls,” says Paul Bayliss, the curator of the Absa collection and director of the gallery and Absa L’atelier Award.

There is a risk, particularly in the case of more valuable works, making them known to the public, he adds.

Yet because of the sheer volume of works in some of these collections — Absa has 16 000 or more, the Nando’s collection boasts 22 000 — most of the curators of these collections are compelled to share the works with audiences beyond the office walls.

“At Sasol, see ourselves as custodians of a collection which not only forms part of the company’s history but part of South Africa’s heritage as well. Thus, we welcome opportunities to share the collection with a greater audience,” says Cate Terblanche, the curator of the Sasol collection.

The public can view the collection by appointment because most of the works are displayed in working environments, she says. The Sasol Art Gallery also hosts a variety of exhibitions, once again open to the public by appointment.

Ayoba Kekere-Ekun works with lines on silk paper to produce ‘Gbórí dúró or Keep Your Head Still’

Ayoba Kekere-Ekun works with lines on silk paper to produce ‘Gbórí dúró or Keep Your Head Still’

In 2004, it published Art @ Work, celebrating a decade of collecting art since democracy. Some of the works in it demonstrate what you might call a typically South African collection — all the familiar names are there from Pierneef, Alexis Preller (an oil on board from 1957) and Maggie Laubser to George Pemba, Ezrom Legae (a drawing), David Goldblatt, William Kentridge (three drawings from the 1980s), Penny Siopis and David Koloane. But the majority of works in it are produced by mostly white emerging artists that are not “big” names, although the majority continue to exhibit.

In his assessment of Sasol’s collection, Clive Kellner, the former director of the Joburg Art Gallery, noted that the Sasol collection “up until 1991 appears conservative, reflected by colourful and decorative works”.

Such types of works in the FirstRand collection have recently been auctioned off, according to its curator, Beth van Heerden. With 5 000 works in the collection — an amalgamation of works belonging to the First National Bank and Rand Merchant Bank — and steered by a policy that is not about “buying art for storage”, Van Heerden is constantly coming up with initiatives to display them.

“We regularly loan out works to other businesses, hotels and, more recently, the Rand Club,” she says.

An edited selection of the 2 000 works in the Sanlam collection was exhibited in 2018 to mark a centenary of its existence.

Works by black artists did not outnumber those by their white contemporaries and had a strong presence in the exhibition through examples of works by Pemba, Gerard Sekoto, Cyprian Shilakoe, Koloane, Sydney Kumalo, Legae and Helen Sebidi.

Sought after: ‘Figures and Fish’ by Blessing Ngobeni

Sought after: ‘Figures and Fish’ by Blessing Ngobeni

Showing works from the Spier collection at the Stellenbosch wine farm and at Union House, the gallery in Cape Town “is essential”, says Mirna Wessels, the director of the Spier Arts Trust. Not only are they keen to share the breadth of the collection but they want the works in it to benefit the artists. “The Spier collection holds many examples of their earlier and often pivotal works, and having work exhibited in a significant collection alongside older, more established artists is obviously beneficial.”

Although many corporate collections start as initiatives to decorate office walls, attention quickly shifts not only to the content and nature of the works but also the identity and position of the artists. This may be a result of the curators having a foot in the art world and intimately knowing the struggle in making a career from art but also because of the length of time they serve in these positions — Bayliss, Hundt, Terblanche and others have been steering these collections and artist awards sponsored by their companies for years, if not decades.

It is troubling that few of these high-profile or well-known collections are steered by black curators. Most curators are silent on the sum of money earmarked for acquisitions annually, the number of works and the artworks that are purchased each year. It appears that mostly, the final decision regarding acquisitions are made by a committee.

As Sanlam’s annual budget is fairly low at R450 000, it relies on an ad hoc committee assembled around the time of each purchase, according to Hundt. Those on the committee are typically art experts; the same has been the case with Sasol acquisition committees in the past. At FirstRand, the selection committee is made up of employees, as they presumably have to live with the artworks. Hundt found that it was difficult engaging staff members about art, particularly if they had little knowledge on the topic.

For corporates with art award programmes, collecting is focused on the artists selected to participate in them — largely emerging artists.

“In the early years of the collection, which was started in the 1980s, the focus was on creating a comprehensive overview of works by South African artists since the 1900s. Over time the focus became increasingly centred on the various Sasol sponsorships, such as the Sasol Wax awards, the KKNK [Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees] and the Sasol New Signatures Art Competition, which was first sponsored in 1990,” says Terblanche.

“Currently, our collecting strategy is focused on the Sasol New Signatures competition and the artists associated with it.”

Sanlam seems to have undergone a similar shift. “The idea of buying good quality works by established artists seems to have been a guiding principle,” observes Hundt in a publication on its collection. He notes that there was a shift towards the “acquisition of important work by younger artists and those of the younger generation. This formed the basis of a collecting policy that is still largely applied today, with an emphasis on representative quality.”

Edoardo Villa’s ‘Confrontation’ is part of the RMB collection. (Keegan Moffatt)

Edoardo Villa’s ‘Confrontation’ is part of the RMB collection. (Keegan Moffatt)

This may have been guided by perceptions that the Sanlam collection was “only representative of ‘Afrikaner’ taste — old art by predominantly white artists supported by the previous government — as expressed by some of my fellow art professionals [but this] is unfounded”.

Van Heerden says, “We have always had a view at looking at international and nationally recognised artists and the gaps we have in the collection. We do look at upcoming young artists in SA and the diaspora. We look at young art prize winners — such as the Absa L’atelier — and get them into our collection. We need to have art that is a representation of the times we live in. Our strategy is therefore to buy from living artists. The prices are not astronomical and you can get in on ground zero to buy and support artists.”

As such, many works from RMB’s Talent Unlocked programme do filter into the FirstRand Collection.

Bayliss believes that acquiring an artwork does not necessarily equate to support of an artist or the creative economy. “You might be buying an artwork for R5 000, you might be buying that artwork for R100 000. But what’s the sustainability after that? So for us, if we say we invest in artists’ careers, it’s not only about purchasing the work, but about how we are providing them a platform. How are we ensuring correct skills transfer? If you look at the direction that the Absa L’atelier award has taken, it’s no longer about giving money. It’s about giving and transferring skills, it’s about sustainability, and empowerment.”

The finalists of the Absa L’atelier Award are part of workshops that deal with different practical areas of growing an artistic practice. They are also included in exhibitions at their gallery in Johannesburg.

“Our work with artists begins after they have accepted the award and step off the stage,” Bayliss adds.

A commitment to supporting artists at the early stage of their careers is perhaps easier to manage. But what is striking are the deeper links corporate collection curators hope to make between the staff at their companies, their clients and the art.

Absa has a presence in 12 countries on the continent and the collection and the Absa L’atelier Award have changed to reflect this more pan-African character.

“We have offices in New York and London. So whatever we do has to be reflected in our offices, we need to reflect who our brand is,” says Bayliss.

Terblanche says Sasol’s art collection promotes “an aesthetic work environment, this has been shown to promote mental well-being, as well as stimulate creative interactions between colleagues working in a company with innovation as mission”.

The synergies between art and commerce are often alluded to in the marketing of the collections and other art programmes.

Carolynne Waterhouse, RMB’s head of the creative council, says, “RMB believes in art as the most universal language. RMB’s corporate collection was not built to have a definite monetary value, but rather to be true to the ethos of the business — one that would have relevance and meaning.”

‘Fearless Thinker’ by Marieke Prinsloo-Rowe is also part of the RMB collection. (Cathy Pinnock)

‘Fearless Thinker’ by Marieke Prinsloo-Rowe is also part of the RMB collection. (Cathy Pinnock)

Hundt is a little more pragmatic. “In the office environment symbolically at least the display of artworks challenges preconceived ideas about what art is and indicates management’s commitment to free and creative thinking,” he observes.

For the employees of these banks to truly enjoy the benefits of being surrounded by art, they would need to frequent the office. With remote work having a huge effect on the banking and financial industry, there is less wall space for art and opportunities for the staff to encounter it.

Van Heerden says, “Nobody has their own office anymore, nor do they come into the office every day. So the focus is on placing the art in meeting rooms and co-working hot-desk spaces.”

Bayliss doesn’t see the reduction of office space having an immediate effect on corporate art collections. “We still have got all these walls in all of these buildings. We have invested in a new gallery,” he says.

FirstRand has a new pop-up gallery, Art & About, and it is hoping it will become a permanent fixture.

So perhaps the effect of remote work on corporate art collections might be seen in larger, more public initiatives to connect the artworks to viewers beyond the boardroom.