ZeitzMOCAA at

Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront.

Photo (right): Iwan Baan

Cape Town artists ride waves in the sea, while their contemporaries in Johannesburg ride their cars at high speed to avoid being hijacked on the way to their inner-city studios.

Such are the clichéd perceptions we might have of the different lifestyles in these two cultural capitals.

There are indeed artists in Cape Town who have dedicated their practice to painting waves — think of Jake Aikman — or other natural environments, while many of Joburg’s most prominent artists not only depict the city in their art but their aesthetics are drawn from it. William Kentridge and Blessing Ngobeni come to mind.

The art scenes in the cities differ too. Cape Town has more established galleries with artists of higher status, due to having closer links to the global art scene, not only through the flood of tourists it attracts but an annual art fair that has a strong international flavour.

There are more emerging artists and galleries to be found in Joburg.

“As an economic and cultural capital, where people come to establish themselves and their careers, Johannesburg has more emerging artists,” says Mandla Sibeko, director of Art Joburg, which opened this week.

Director of Art Joburg Mandla Sibeko sees Joburg as an economic and cultural capital where artists come to establish their careers.

Director of Art Joburg Mandla Sibeko sees Joburg as an economic and cultural capital where artists come to establish their careers.

There are more private art museums in Cape Town than Joburg, perhaps also due to the tourist numbers, yet both art capitals have several different art nodes spread across the city and beyond.

Hoosein Mahomed is a co-founder of Church, a non-profit gallery in Cape Town’s city centre.

Hoosein Mahomed is a co-founder of Church, a non-profit gallery in Cape Town’s city centre.

Covid-19 appears to have disrupted not only the infrastructural dynamics, but perhaps the content of art coming out of these cities. Given the lockdowns, which forced everyone into isolation, geography mattered little as art trading and life in general moved online.

This might not have replaced face-to-face dealings but it proved a lifeline for galleries, especially in Joburg, engendering a more globalised outlook, particularly in the absence of local sales.

“Without the internet, I think we would have been one of the galleries that would have closed. At present, I would say 80% of our collectors are from outside South Africa,” says Banele Khoza, an artist and founder of Joburg’s BKhz gallery.

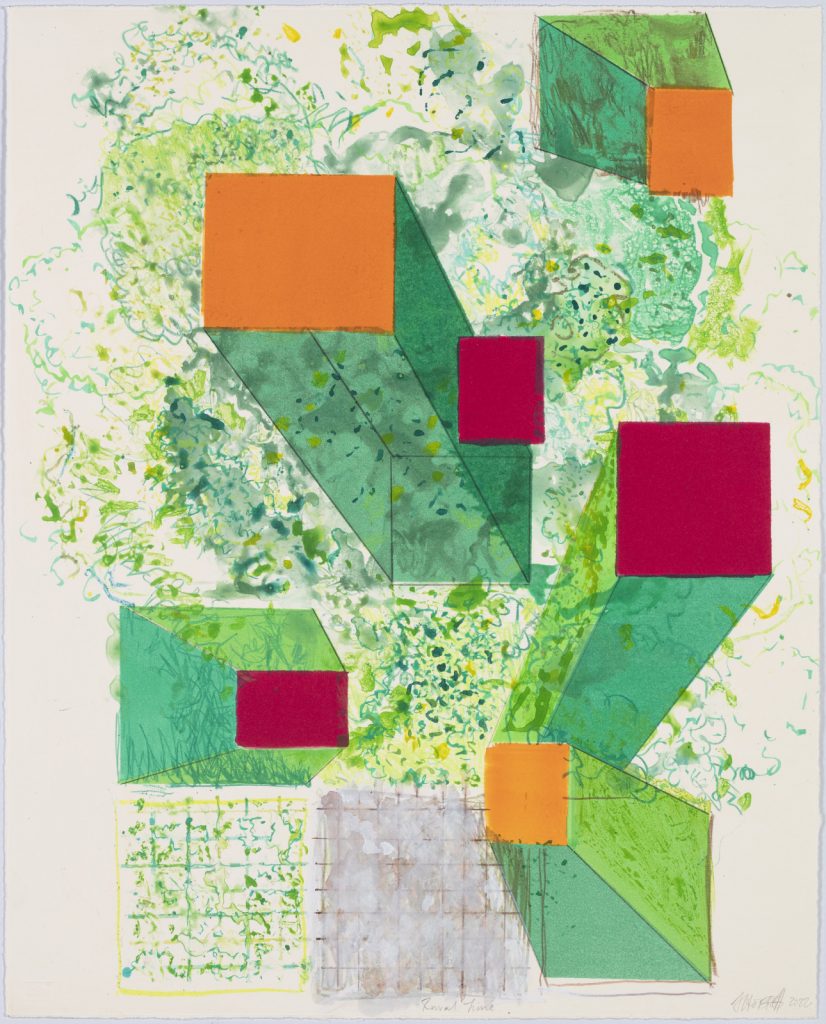

‘Rural Time’ by Stephen Hobbs, who has a studio in Joburg’s CBD. Photo (right): Iwan Baan

‘Rural Time’ by Stephen Hobbs, who has a studio in Joburg’s CBD. Photo (right): Iwan Baan

The pandemic, and possibly its impact on livelihoods, saw a marked decrease in local sales, Khoza says.

In this way, being a Joburg or Cape Town gallery mattered little — with the focus on the global art market.

Dwindling income from local collectors saw BKhz focus on participating in art fairs outside the African continent and Khoza made visits to European fairs — such as Art Basel — to get a grip on the tastes and movements shaping art production on that continent.

This shift in outlook has meant BKhz won’t be participating in Art Joburg as it has become less of a priority to connect with Joburg collectors for this young gallery.

“Most of the galleries that showcase in Art Joburg have become international. They sell works to buyers overseas and they sell to buyers here. It’s very difficult to say if they rely on local collectors. On average, a gallery is attending four to five art fairs globally,” observes Sibeko.

The digital migration that Covid-19 encouraged saw a marked increase in online and pop-up exhibitions, galleries and platforms (such as Latitudes Online) advancing different kinds of models that have, to some degree, transcended geographic boundaries.

Forms Gallery, an online space founded by Joburg-based Anthea Buys, has staged shows in Joburg and Cape Town. Curator-driven projects by Reservoir (Heinrich Groenewald and Shona van der Merwe) or Studio Nxumalo (Musa Nxumalo) and Martin Projects (Igsaan Martin) have seen exhibitions staged in and outside traditional white cube spaces. This has expanded dialogues about art in both cities. However, there is a sense that these entities have not penetrated traditional gatekeeping boundaries.

“It was disappointing that some of these new platforms weren’t given a booth at Art Joburg because they didn’t have a physical space. So, you know, while we have seen a lot of pop-ups and new models, they have been overlooked,” says Hoosein Mahomed, co-founder of Church, a non-profit gallery in Cape Town.

This experimental space, as its title suggests, is, on Church Street, in Cape Town’s inner city, which has become a vital art node with Eclectica, Worldart, Nel and the AVA galleries clustered together.

With newcomer The Fourth and Whatiftheworld based in the city, and the Goodman Gallery relocating to De Waterkant, the Cape Town art scene has seen a shift towards the city, away from Woodstock — albeit Blank, Stevenson, Smac and 131 Gallery (also a newcomer) are there.

“Where else in Africa, perhaps other than Cairo, can you enjoy seeing art in a city? This is special and our ward councillor and the premier want to ensure Church Street retains an art character,” says Mahomed.

Interestingly, the opposite has been the case in Joburg with the strengthening of the art cluster in the burbs — Rosebank and Parkhurst. This has been influenced by the collapse of Maboneng, in the city centre, as a cultural and art node.

“It’s become rough here. Almost every establishment has been turned into a bar,” says artist Stephen Hobbs who has retained his Maboneng studio.

“In some ways, it is more authentic and real than the manicured urban safari offering that used to attract the Bryanston crowd with the quick onramp-offramp experience [the highway facilitated],” adds Hobbs.

The Braamfontein art clustering has also imploded, though the Kalashnikovv Gallery has retained a space there, despite opening a project space in the burbs. There seems to be a mix of reasons for the exodus of galleries.

Khoza noticed that his audience was gravitating towards Rosebank. In response to this, combined with not being able to extend his Braamfontein lease, he opened up a smaller gallery at Trumpet, on the Keyes Art Mile. It is, however, eerily quiet there most days of the week.

Art-making is undoubtedly influenced by the environments where artists live, however, during the lockdowns, they were cut off from multiple sources and seem to have either withdrawn deeper into their practice or their home environment. Domestic spaces, to a certain degree, became a more prominent feature, whether artists were in Joburg, Cape Town or elsewhere.

Cinthia Mulanga, a young Joburg artist, came to prominence during the pandemic with paintings of women in interior spaces. With the reported rise in domestic violence, she pondered whether these settings were places of safety.

Hobbs, who had immigrated to a bucolic setting outside Cork in Ireland, zoned in on the history of the house he was renting, eventually producing a series of architectonic works based on the plans of the house, employing the cardboard boxes his online deliveries came in as his main material.

This body of work will show at the David Krut gallery in Joburg.

The cardboard would prove to have a deeper significance since he returned to live in South Africa and, in the process, moved home six times.

“For many creative people who weren’t completely pulverised by the experience, they had the opportunity to dream, to think, to re-evaluate, to decide where their priorities lie. As a consequence, a deep richness at a cultural level is manifesting in some areas with some artists,” says Hobbs.

Other artists, whether in Cape Town, Joburg or Lagos, were more fixated on the online environment, observing the kind of art movements that seemed to be finding traction during this time. Portraiture was one such trend, which exploded during the pandemic and remains a notable feature of expression for artists from the continent.

“I think the period of Covid restrictions, which prevented you from travelling, gave rise to specific canons (across borders), like portraiture. It became so popular with

collectors that it almost felt like that was all they wanted. I immediately found that a bit problematic. What happens to the minimalist works?” asks Khoza.

Art Joburg might well see works announcing a push-back against the portraiture genre. Church is purposely going to present non-figurative artworks, says Mahomed.

Since lockdowns ceased, artists have been to some degree — Hobbs says he remains more home-bound than before — reconnecting with their city and feeding off its characteristics.

Regional differences remain pertinent to art production, though sometimes they manifest in less obvious ways. Joburg artists are forced to confront inequality and social, urban degradation in ways that some

Cape Town artists are not. The splendour of Cape Town’s natural beauty will continue to activate the creative juices, even for artists fixated with man-made designs, such as Gerhard Marx, who is known for his manipulation of maps.

“My work engages me in a contemplative, philosophical and perhaps meditative manner. Access to non-human spaces in the form of nature is crucial to this process — wandering, walking, hiking, running, chance encounters and swimming are crucial to my practice and well-being,” says Marx, who moved from Joburg to Cape Town.

The entrepreneurial spirit, which runs deep through Joburg’s core identity, makes it a city where new ideas or models might more readily take shape, implies Sibeko.

“People get things done here. There are a lot of artists who don’t wait for anybody.

“What also makes this scene unique is the fact that there’s a powerful cultural community that’s shaping South Africa’s cultural landscape as a whole. People in Johannesburg are the decision-makers,” Sibeko says.

Art Joburg takes place at the Sandton Convention Centre until 4 September. A Short Life with Bungalow Bliss by Hobbs will show at David Krut and multimedia installation Shallow Sleep at his studio in Maboneng as part of the Art Joburg Open City programme.

A painting by Wyclef Mandopa at Art Joburg, which opened this week.

A painting by Wyclef Mandopa at Art Joburg, which opened this week.

Cape Town artists ride waves in the sea, while their contemporaries in Joburg ride their cars at high speeds to avoid being hijacked on the way to their inner-city studios. Such are the cliched perceptions we might have of the different lifestyles in these two cultural capitals. There are indeed artists in Cape Town who have dedicated their practice to painting waves – think of Jake Aikman – or natural environments, while many of Joburg’s most prominent artists not only depict the city in their art but their aesthetics are drawn from it from. William Kentridge or Blessing Ngobeni come to mind.

The art scenes in both cities have differed too. Cape Town has more established galleries with artists of higher status due to its closer links to the global art scene, not only through the flood of tourists it attracts but an annual art fair that has a strong international flavour.

There are more emerging artists and galleries to be found in Joburg.

“As an economic and cultural capital, where people come to establish themselves and their careers, Johannesburg has more emerging artists,” comments Mandla Sibeko, director of Art Joburg, which opens this week.

There are more private art museums in Cape Town than Joburg, perhaps also due to the tourist numbers yet both art capitals have had several different art nodes spread across the city and beyond.

Covid-19 appears to have disrupted not only the infrastructural dynamics but perhaps the content of art too coming out of these cities. Given the lockdowns which forced everyone into isolation, geography mattered little as art trading and life in general moved online.

This may not have replaced face-to-face dealings but it proved a lifeline for galleries and generated, especially in Joburg, engendering a more globalised outlook, particularly in the absence of local sales.

“Without the internet, I think would have been one of the galleries that would have closed. At present I would say 80% of our collectors are from outside South Africa,” says Banele Khoza, an artist and founder of BKhz, a Joburg-based gallery.

The pandemic and possibly its impact on livelihoods saw a marked decrease in local sales, according to Khoza.

In this way being a Joburg or Cape Town-based gallery has mattered little – with the focus on the global art market. Dwindling income from local collectors saw BKhz focus on participating in art fairs outside the African continent and Khoza made visits to European fairs – Art Basel – to get a grip on the tastes and movements shaping art production on that continent. This shift in outlook has meant BKhz won’t be participating in Art Joburg as it has become less of a priority to connect with Joburg collectors for this young gallery.

“Most of the galleries that showcase in Art Joburg have become international. They sell works to buyers overseas and they sell to buyers here. It’s very difficult to say if they rely on local collectors. On average, a gallery is attending four to five art fairs globally,” observes Sibeko.

The digital migration that Covid-19 encouraged saw a marked increase in online and pop-up exhibitions, galleries and platforms (such as Latitudes Online) advancing different kinds of models that have to some degree transcended geographic boundaries. Forms gallery, an online space founded by Joburg-based Anthea Buys, has staged shows in Joburg and Cape Town. Curator-driven projects by Reservoir (Heinrich Groenewald and Shona van der Merwe) or Studio Nxumalo (Musa Nxumalo) and Martin Projects (Igsaan Martin) have seen exhibitions staged in and outside traditional white cube spaces. This has expanded dialogues about art in both cities. However, there is a sense that these entities have not penetrated traditional gatekeeping boundaries.

“It was disappointing that some of these new platforms weren’t given a booth at Art Joburg because they didn’t have a physical space. So you know while we have seen a lot of pop-ups and new models, they have been overlooked,” says Hoosein Mahomed, co-founder of Church, a non-profit gallery in Cape Town.

This experimental space, as its title suggests, is located in Cape Town’s inner city, on Church Street, which has become a vital art node with Eclectica, Worldart, Nel and the AVA galleries clustered together. With newcomer The Fourth and Whatiftheworld based in the city and Goodman Gallery relocating to De Waterkant, the Cape Town art scene has seen a shift towards the city, away from Woodstock – albeit that Blank, Stevenson, Smac and 131 Gallery (also a newcomer) are based there.

“Where else in Africa, perhaps other than Cairo, can you enjoy seeing art in a city? This is special and our ward councillor and the premier want to ensure that Church street retains an art character,” says Mahomed.

Interestingly, the opposite has been the case in Joburg with the strengthening of the art cluster in the ‘burbs – in Rosebank, Parkhurst. This has been influenced by the collapse of Maboneng as a cultural or art node.

“It’s become rough here. Almost every establishment has been turned into a bar,” says artist Stephen Hobbs who has retained his Maboneng-based studio.

“In some ways, it is more authentic and real than the manicured urban Safari offering that used to attract the Bryanston crowd with a quick on ramp, off ramp, experience (the highway facilitated),” adds Hobbs.

The Braamfontein art clustering also imploded, though Kalashnikovv gallery has retained a space there, despite opening a project space in the burbs. There seems to be a mix of reasons for the exodus of galleries from there. Khoza noticed that his audience was gravitating towards Rosebank. In response to this, combined with not being able to extend his Braamfontein lease, he opened up a smaller gallery at Trumpet, on the Keyes Art Mile. It is, however, eerily quiet there most days of the week.

Art making is undoubtedly influenced by the environments where artists live, however, during lockdowns they were cut off from multiple sources and seem to have either withdrawn deeper into their practice, or their home environment. Domestic spaces to a certain degree became a more prominent feature, whether artists were in Joburg or Cape Town, or elsewhere.

Cinthia Mulanga, a young Joburg-based artist, came to prominence during the pandemic with paintings of women in interior spaces and with a reported rise in domestic violence she pondered whether these settings were places of safety. Hobbs, who had immigrated to a bucolic setting outside Cork in Ireland, zoned in on the history of the house he was renting, eventually producing a series of architectonic works based on the plans of the house, employing the cardboard boxes that all his online deliveries came in, as his main material. This body of work will show at the David Krut gallery in Joburg. The cardboard would prove to have a deeper significance since he returned to live in South Africa and in the process moved home six times.

“For many creative people who weren’t completely pulverised by the experience, they had the opportunity to dream, to think, to re-evaluate, to decide where their priorities lie. As a consequence, a deep richness at a cultural level is manifesting in some areas with some artists,” says Hobbs.

Other artists, whether in Cape Town, Joburg or Lagos, were more fixated on the online environment, observing the kind of art movements that seemed to be finding traction during this time. Portraiture was one such trend, which exploded during the pandemic and remains a notable feature of expression for artists from the continent.

“I think the period of COVID restrictions which prevented you from travelling gave rise to specific canons (across borders) like portraiture. It became so popular with collectors that it almost felt like that was all they wanted. I immediately found that a bit problematic. What happens to the minimalist works?” asks Khoza.

Manthe Ribane poses with a work by Georgina Gratrix at Art Joburg.

Manthe Ribane poses with a work by Georgina Gratrix at Art Joburg.

Art Joburg may well see works announcing a push-back against the portraiture genre. Church is purposively going to present non-figurative artworks, says Mahomed.

Since lockdowns ceased artists have been to some degree – Hobbs says he remains more home-bound than before – reconnecting with their cities and feeding off its characteristics. Regional differences remain pertinent to art production, though sometimes they manifest in less obvious ways. Joburg-based artists are forced to confront inequality and social, urban degradation in ways that some Cape Town-based artists are not. The splendour of Cape Town’s natural beauty will continue to activate the creative juices, even for artists fixated with manmade designs, such as Gerhard Marx, who is known for his manipulation of maps.

“My work engages me in a contemplative, philosophical and perhaps meditative manner, access to non-human spaces in the form of nature is crucial to this process – wandering, walking, hiking, running, chance encounters and swimming are crucial to my practice and well-being,” says Marx.

The entrepreneurial spirit that runs deep through Joburg’s core identity, makes it a city where new ideas or models might more readily take shape, implies Sibeko.

“People get things done here. There are a lot of artists who don’t wait for anybody. What also makes this scene unique is also the fact that there’s a powerful cultural community that’s shaping South Africa’s cultural landscape as a whole. People in Johannesburg are the decision makers,” opines Sibeko.

Art Joburg takes place at the Sandton Convention Centre from September 2 to 4. A Short Life with Bungalow Bliss by Hobbs will show at David Krut and a multi-media installation Shallow Sleep at his studio in Maboneng. as part of the Art Joburg Open City Programme.

<WIN!>

We’re giving away two double tickets to FNB Art Joburg. All you have to do to qualify to win is follow @fnbartjoburg and @mailandguardian_Friday and tag five friends with the hashtags #FNBArtJoburg and #MGFriday.