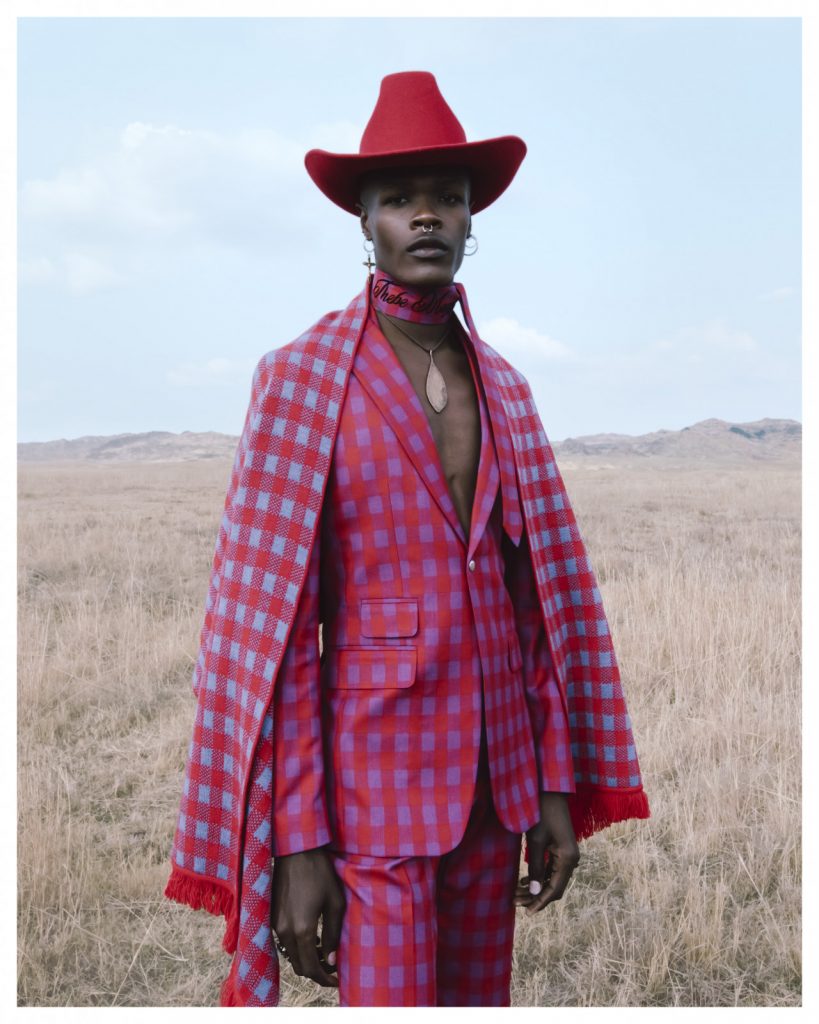

The result of Magugu’s sartorial engagement with Valentino’s creative director Pierpaolo Piccioli saw the two designers swap their creations and rework them into their own style for Vogue magazine. Photo: Delali Ayivi

As a conceptual artist, British-Nigerian Yinka Shonibare has always had vast, world-changing intentions and there is nothing tentative about the title of his first Cape Town solo at Goodman Gallery.

Restitution of the Mind and Soul is a statement that gets under your skin, occupying your dreams and refracting through multiple historic and contemporary contexts in transformative ways.

“The African contribution to modernism has never really been celebrated in the way it ought to be,” says Shonibare. This vital and declarative new body of work might be understood as both a remedy and a response to the persistent cultural condition of amnesia and negation — particularly when it comes to Africa’s constitutive role in the western modernist canon.

Restitution of the Mind and Soul is timeous in more ways than one. Firstly, it happens a full century on from the 1920s, recalling the searching, post-World War I fervour of modernism, and inducing an uncanny sense of diasporic déjà vu.

Its retrospective gaze is tinted with a radical utopian proposition — what might deep, retrospective acknowledgement make possible?

“During the war in Europe a lot of the Dada artists and the surrealists were against this western power that ended in the use of horrible weapons. They were looking to challenge the over-industrialised system that rejects nature and environment. And then there was [Sigmund] Freud.

“They were looking to dreaming, to the unconscious. They found a lot of that spirituality within African cultures. Tristan Tzara and the avant-garde artists, and others like Modigliani, Matisse, Brancusi, Picasso, took their influences from African artists,” says Shonibare.

“Paris in the 1920s was a space for African expression, a celebration of African art — jazz, Josephine Baker’s dance. This was a deliberate celebration of the improvisational, the spiritual. But, there was a complete absence of acknowledgement of the people who had inspired it. In the late 1920s and 1930s, there was the Harlem Renaissance and African culture was celebrated. But when World War II happened, there was a recession and all of that stopped.”

Secondly, this exhibition happens during ongoing negotiations around the restitution of looted African artefacts in the aftermath of the colonial empire. Last month the Horniman Museum and Gardens in London announced it would be returning to Nigeria 72 Benin bronzes looted during the British military raid in 1897.

Objects looted during this raid ended up in around 150 museums across Europe and America. Repatriation of these artefacts and others is gaining momentum.

“We’re entering a new African renaissance,” says Shonibare.

Using Picasso’s collection of African artefacts as a starting point, his works juxtapose chosen artefacts with classical European antiquity.

“I want to challenge notions of cultural authenticity by creating a composite ideology, ‘a third myth’, exploring appropriation, cultural identity and the ability to transform beyond what is expected and therefore compels us to contemplate our world differently,” says the artist.

The exhibition features a series of large, jazzy hand-stitched quilts; painted masks, based on those that gave rise to the deconstructed faces of the two figures in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Cubism; and hybrid sculptures that bring together African ancestors and European mythological beings in boldly syncretic new forms.

In Magugu’s Genealogy collection he took inspiration from the women in his family, using dated images from the 80s as his source, he transformed their DIY style into high fashion. Aart Verrips

In Magugu’s Genealogy collection he took inspiration from the women in his family, using dated images from the 80s as his source, he transformed their DIY style into high fashion. Aart Verrips

Accompanying these creations is a slide projection of archival images from avant-garde Paris in the early years of the 20th century. Titled Paris á Noir II [Paris to Black II] (2022), it highlights the cultural fluctuations “between facilitating black empowerment and reinforcing the fetishisation of African cultures by the mostly white bourgeois elite”.

Refuting purist, imperial notions of culture, the talismanic forms hold a magical power of their own new order, carrying forward the artist’s ongoing project of “mongrelisation”.

Shonibare, who was born in 1962, just two years into Nigerian independence, reflects on the source of this applied-life philosophy.

“I’d been indoctrinated to reject my own heritage, so I had to rediscover that. I grew up thinking my heritage and culture were ‘primitive’ because of my colonial education … Western culture was prioritised, so you would learn Shakespeare and recite western poems and sing ‘London Bridge is falling down’, but you were in Lagos,” he says.

“Restitution is a process of taking back something that you’ve lost. But also understanding that you cannot take it back in its original context.

“There is a displacement, but you’re still connected to that heritage. You have to be realistic about how those expressions manifest, so that’s the process of mongrelisation — that we are proud to be a mixture of all these things. This is not a rejection of modernisation or modernity, it is an incorporation.”

His influences are defiantly diverse. The quilts in this show, for example, draw on the long tradition of African-American quilt-making.

“People didn’t have fabric to work with, so they would cut the material from old clothes and stitch them together to make pictures. My choice of quilts is a deliberate sidestepping the western history of art — you see the seams, threads, the process of making. It’s a modernist approach where the process is visible. They’re bold and textured. African music is like that, jazz — it’s improvisational. And there are other elements from music — pattern, repetition.

In the way that African ceremonies are engaging and involving, this show is about engaging my audience and saying, ‘celebrate this, enjoy this!’”

Shonibare’s spectacular appropriative strategies range from assuming the role of Dorian Gray in Oscar Wilde’s cautionary 19th-century horror story about the doomed hopelessness of trying to stay forever young, to posting huge posters of himself in cross-cultural, time-collapsing drag on the subterranean walls of London’s underground in the late 1990s. But he is probably best known for his use of Dutch wax-print fabric.

Finely attired in this brightly patterned cloth, the often headless 18th- and 19th-century aristocratic figures who populate his installations, photographs and video works, romp around in a lewd and rapacious fashion that blatantly belies the myth of mannered restraint coded into the notion of western civility and enlightenment. The fabric itself, it turned out, held a myth of its own.

Although it seemed quintessentially African, it was through Shonibare’s interventions that audiences learned of its colonial-era origins and circuits of distribution.

Modelled on the homespun technique of Indonesian batik, the fabric was mass produced by Dutch industrialists in the 19th century, shunned by Indonesia, and then embraced by West African women, who adopted and adapted it as their own.

Shonibare’s use of Dutch wax-print fabric went a long way to popularising the knowledge that globalisation is not the contemporary phenomenon many assume it to be. Our world ricochets and quakes with intercultural hauntings from the past.

These tensions were explored in engaging detail during a packed public dialogue between the artist and Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa’s executive director and chief curator Koyo Kouoh on Saturday.

During the Q&A session, Shonibare’s embrace of being “honoured as commander of the British Empire” came under critical fire, with fellow trailblazer Tracey Rose interrogating his “Trojan horse” insider/outsider approach to dismantling institutions of empire.

He held fast to his paradoxical position, defending the value of generating perplexity and dialogue around assemblages that apparently don’t add up. Rose did not seem to accept this.

Shonibare is a mediatic wizard, who uses materials and media in ways that plant enduring questions about the racialised power structures that undergird the globalised world.

He pushes expectation and assumption into new dimensions.

The patterns that adorn the surfaces of his hybrid masks and sculptures have been hand-painted onto the objects, like a second skin. “Yes, the bodies have been taken over by African patents, if you like,” he quips.

TMagugu is interested in style, but married to politics. In his DoubleThink collection he shone a light on the figure of the whistleblower in the context of corruption. Image: Aart Verrips

TMagugu is interested in style, but married to politics. In his DoubleThink collection he shone a light on the figure of the whistleblower in the context of corruption. Image: Aart Verrips

This technique can also be seen in his ecstatic, painted-fibreglass Wind Sculptures, one of which alighted (in 2019) in the gardens of Cape Town’s Norval Foundation. In 2016, Wind Sculpture VII became the first sculpture to be permanently installed at the entrance to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American Art in Washington DC.

The patterns themselves are a mongrelisation of a mongrelisation. Inspired by wax-print patterns, they include abstracted waves, snakes, feathers, flowers, suns.

Shonibare explains: “The reason I started using the Roman figures goes back to when Donald Trump was in power and the alt-right in the US were using classical sculptures and imagery as a sign of the superiority of western heritage and culture. And I thought there was a gross misperception about that imagery.

“The Greeks and Romans painted them. And it was time that made them white. The paints just faded. “There is no such thing as a culture that stands alone. The Greeks were inspired by the Egyptians — cultures take from each other. I started making interventions that morphed and developed further. What I’ve done is to return other influences to those marble sculptures.”

It is these varied, bold, subtle, mongrelised acts of restitution and return that give Shonibare’s work its paradoxical, time-travelling power, shifting it from parody towards a new spiritual register.

Restitution of the Mind and Soul will be on at the Goodman Gallery until 12 November.