‘Music chose me’: South African Mo Laudi is holding an exhibition titled ‘Globalisto: A Philosophy in Flux’ in the French city of Saint-Étienne. Photo: Jean Picon

Mo Laudi and James Webb, two expatriate South African visual artists interested in sound and its relationship to sight, are holding court in France.

Laudi, a DJ, artist and curator living in Paris, has organised a large museum show in the eastern-central city of Saint-Étienne. Webb, who is from Cape Town but lives in Stockholm, Sweden, is a participant in the Lyon Biennale, one of Europe’s leading showcases for new art.

Laudi’s exhibition Globalisto: A Philosophy in Flux features work by 19 artists, among them Amsterdam-based Moshekwa Langa and Samson Kambalu, a Malawian living in Oxford, England. It offers an elaboration of Laudi’s self-styled “globalisto philosophy”, a pan-Africanist idea rooted in “radical hospitality”, “openness” and the aspiration to create a “counsel culture” through art.

That the objects on view, among them striking textile pieces by Langa, Kambalu and Antwerp-based Nigerian Otobong Nkanga, are mute doesn’t lessen the importance of sound in their appreciation. “To restore silence is the role of objects,” wrote Samuel Beckett in his 1955 novel Molloy.

Webb, a local pioneer in the use of sound in art, has a keen grasp on the power of silence. For his Lyon Biennale presentation, he has produced a new body of work framed around the disruptive potential of an unanswered question.

Speakers at four venues across Lyon broadcast a series of questions, voiced by Johannesburg playwright Sylvaine Strike. Spoken at 10-second intervals in English and French, the questions address park users, museum-goers and specific objects, among them an urn that dispensed the ancient cure-all medicine theriac.

The Lyon work is a continuation of a project started in 2018 when Webb recorded a voice posing questions to a Chewa mask made in the image of Elvis Presley.

“To whom am I speaking?” asks Strike of a Roman coin from 70CE on view in a former home-appliance factory used by the biennale. “What languages do you speak? Where were you created? What are your memories of that place? What were you worth when you first circulated? How do you see your value now?”

No answers are offered to Webb’s scripted questions; the enquiry, and the silence around it, is all.

That France is receptive to émigré South African artists with a love of music and sonic mischief is nothing new. Shortly after his arrival in Paris in 1947, painter Gerard Sekoto landed a regular gig as a pianist at a bar in fashionable Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

In James Webb’s work at the Lyon Biennale, a series of personal questions is addressed to an urn. (Aurelie Troccon/Musee des Hospices Civils de Lyon)

In James Webb’s work at the Lyon Biennale, a series of personal questions is addressed to an urn. (Aurelie Troccon/Musee des Hospices Civils de Lyon)

After an unrehearsed audition in which he “strummed and chanted and groaned and shouted”, Sekoto was contracted to play a repertoire of jazz and African-American spirituals. The gig provided income and community at a difficult time in Sekoto’s exile from home.

Sekoto is an important ancestor for Laudi. Born Ntshepe Bopape in Polokwane in 1978, when he was 12, Laudi was awarded a prize to create a mural honouring Sekoto at the Polokwane Art Museum. He learnt Sekoto, too, had lived in Polokwane, working as a schoolteacher there in the 1930s before pursuing art professionally and moving to France.

It was in Paris, as part of his first outing as a curator at Bonne Espérance Gallery last year, that Laudi paid homage to Sekoto. Unable to secure Sekoto’s drawings of Parisian nightclubs for his exhibition Salon Globalisto, Laudi built a sound installation in a nearby church instead. It replayed songs from Sekoto’s 1959 Negro Spirituals, released by the French label Les Disques Deva.

“You could hear Sekoto sing every Saturday for the duration of the exhibition,” says Laudi when we speak via Zoom. “To hear him sing, it was so much more powerful than having a drawing.”

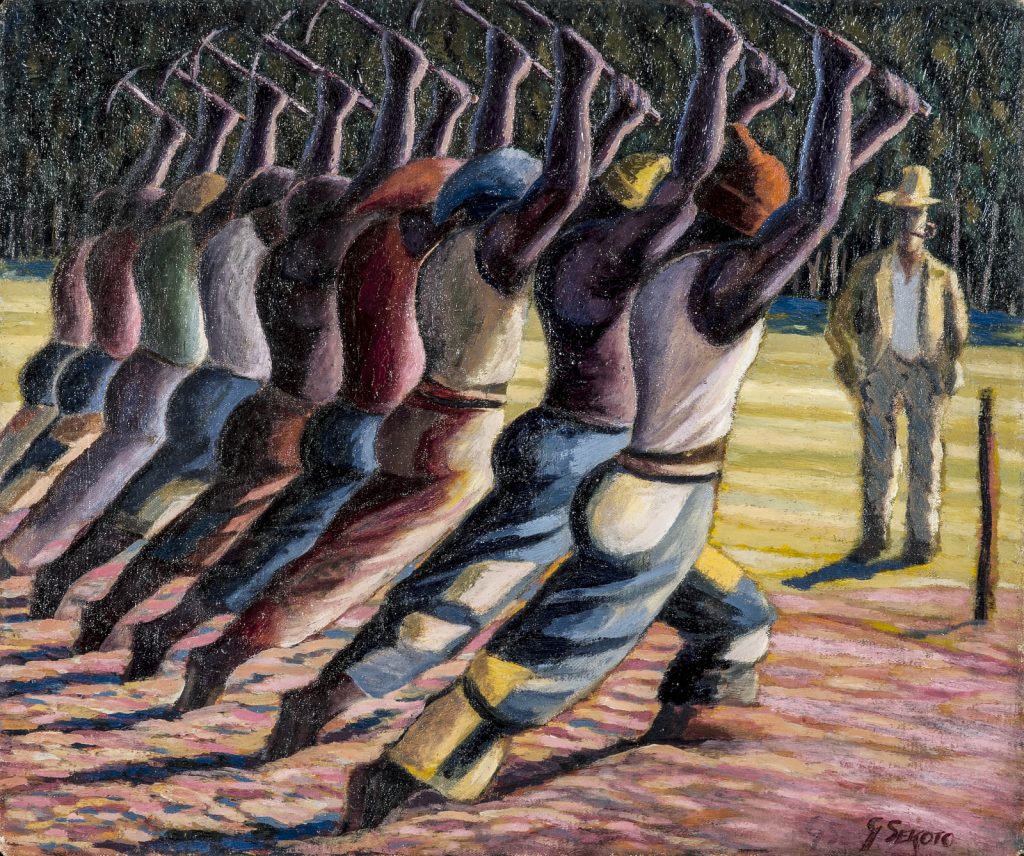

Upping the ante, Laudi’s exhibition at Saint-Étienne’s Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (up until 16 October) is introduced with Sekoto’s important painting Song of the Pick (1947). The composition depicts a row of nine black men, picks raised in unison, attacking a patch of earth. A pipe-smoking white man, hands tucked into his pockets, oversees their labour.

“It is breathtaking,” enthuses Laudi of Sekoto’s work, which is owned by mining house South32. “It makes me think of singing, the continuum of the work song and its connection to labour and prison songs. It makes you think of the power of song and community.”

Nigerian Otobong Nkanga’s ‘Kolanut Tales, Dismembered’ on Mo Laudi’s exhibition ‘Globalisto: A Philosophy in Flux’.

Nigerian Otobong Nkanga’s ‘Kolanut Tales, Dismembered’ on Mo Laudi’s exhibition ‘Globalisto: A Philosophy in Flux’. Laudi’s enthusiastic account frequently breaks down. In these moments he reverts to imitating the sounds suggested by the painting, the “sensorial explosion” of Sekoto’s hoisted picks about to break open the ground.

It is claimed Sekoto based Song of the Pick on a 1930s photograph by Andrew Goldie showing nine black labourers with picks being watched by a white master. Laudi repeats this to me. It is only a part of this iconic painting’s story.

In 1938, Eastern Cape artist Dorothy Kay produced a wildly popular, and also widely circulated, etching titled Song of the Pick. Her skilfully conceived work portrays four bare-chested men in a sculptural line hoisting picks.

Sekoto began to explore the same subject in a 1939 watercolour. But it is his 1947 oil composition that refutes the heroic terms of Kay’s study of bare-chested labour, offering in its place something suggestive of unified purpose in the face of white exploitation.

“When people come together, they can fight with strength,” Laudi summarises.

Laudi’s own sense of the power of community was shaped by his love of music. He name-checks Run-DMC, Tupac, A Tribe Called Quest, Mos Def and Saul Williams as early influences. For a time, he went by the rap and graffiti handle “Capone”.

He adopted the “Mo Laudi” moniker after moving to London in the early 2000s.

“Music choose me in some ways,” says Laudi. “In London, I DJed every night at one point. It created a community, a home away from home. You find a bar and bring your whole gang of friends.

“I think Sekoto in Paris struggled with that — finding a community. It is what made him dilapidated and end up in a mental hospital.”

Laudi’s move to Paris in 2010 has been less traumatic. Alongside his commercial music pursuits, he increasingly hustled for recognition in the art world. Earlier this year, he showed a suite of abstract paintings at the Dakar Bienniale, accompanied by a sound piece. The work was devoted to the pioneering abstract painter Ernest Mancoba, a colleague of Sekoto at Khaiso High School in Polokwane.

Part of Webb’s Lyon Biennale show.

Part of Webb’s Lyon Biennale show.

Laudi’s upbringing cultivated his appreciation for sound. His parents have strong links to the Polokwane Choral Society. Founded in 1977, this storied choir has enjoyed great demand and even sang at Walter Sisulu’s funeral in 2003. Laudi’s father was a singer and his mother a conductor and director.

In 2016, Laudi’s sister, the award-winning artist Dineo Bopape, detailed the choir’s history in her exhibition Sa Kosa Ke Lerole at the National Arts Festival in Makhanda.

“My sister has always been around somehow,” says Laudi of his better-known sibling.

“She has used my music in her work. I asked her to do the cover of a release I did a while back.”

He offers this by way of registering a larger point about the “blurring of scenes” that has been central to his multifaceted career — and arguably Webb too, who once fronted a band and has also worked in theatre, producing sound for Athol Fugard’s The Bird Watchers.

Gerard Sekoto’s ‘Song of the Pick.

Gerard Sekoto’s ‘Song of the Pick.

Prompted by his recent expansion into the field of curating, I ask Laudi if curating an exhibition differs from compiling a playlist or DJ mix.

“Vastly,” he says after protracted laughter. “It’s incomparable, but it is comparable. You have to have patience, passion and knowledge. It’s years and years of really feeling the work and nurturing relationships. It is more nuanced. Nah, it’s not the same as making a playlist.”

Globalisto: A Philosophy in Flux is at Saint-Etienne Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MAMC+) until 16 October.

The 16th Lyon Biennale, featuring James Webb, runs in the city of Lyon until 31 December.