Melinda Ferguson doesn’t mince her words. She masticates them with precision into sweet-sour smoothies of jaw-dropping experience. She sips them sometimes with measured control; other times she spurts them out in staccato, bulimic episodes – a throwback to the eating disorders and addictions she suffered for many years before her redemption as a deservedly acclaimed author and publisher.

I must confess to having never read Ferguson’s bestsellers Smacked, Cracked, and Crashed. I have an aversion towards memoirs with all entrails exposed, in which there’s a degree of swagger in the stagger towards self-destruction. But Bamboozled — her latest tome — has changed my mind. In it she provides a partial but compelling recapitulation of these earlier books. She does so with such unfettered honesty and skinless vulnerability that one can only wonder how the hell she possessed the resilience, not only to crawl out of her vortex of multiple addictions, but to survive, and ultimately, to thrive. For that alone she deserves respect. For her lyrical, literary prowess and unquenchable curiosity for answers, she deserves all the accolades she has received.

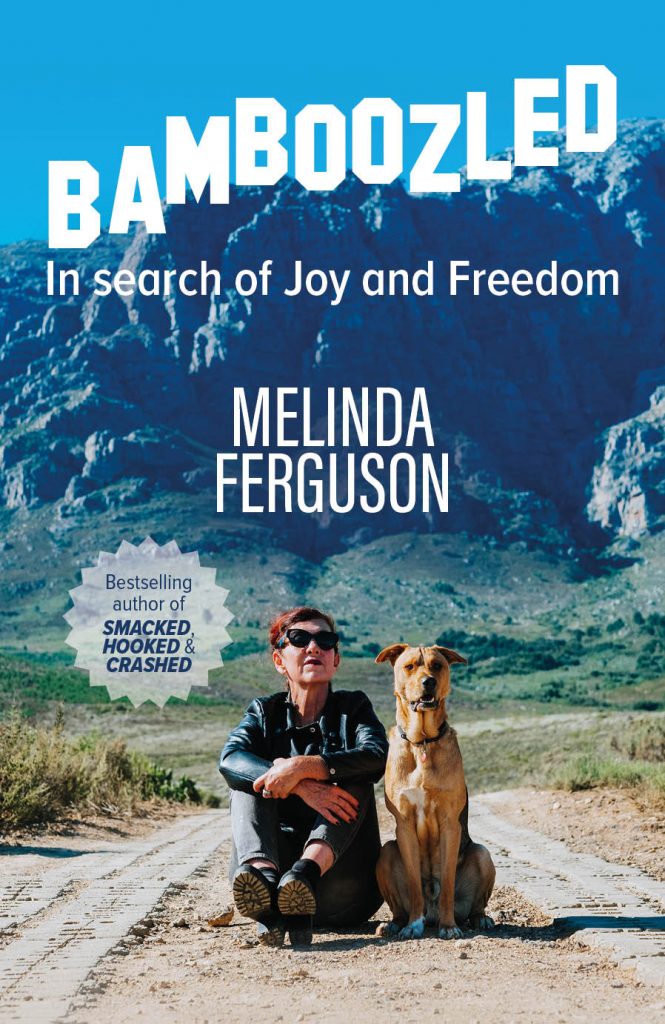

Although Bamboozled is an apt title — an apogee of sorts to what might be regarded as a tetralogy of self-discovery — an alternative title that springs to mind is “Controlled”. Essentially, the subject of art is the self in all its untidy incarnations, which we inevitably edit to blunt the more jagged shards of memory. Ferguson refuses to do this. In Bamboozled, it is her quest — as attested on the book cover — to gain “joy in a world gone mad”. But it is also about trying to attain control, meaning and self-forgiveness. Hers is the painful, surface-rupturing journey of slaying dragons, towards acceptance of failure and, the even more difficult, acknowledgement of success.

Ferguson’s odyssey is essentially a success story, not simply in creative, financial, reputational terms, but as the journey of self-actualisation on which she has embarked, struggling to overcome the doubt that she deserves to be happy; that she has earned the accolades without feeling fraudulent. She also acknowledges the arduous process of writing itself. In the author’s note she notes, “Writing a memoir can be brutal” and concurs with someone who wrote: “Writing is like banging your head against a wall until you finish it.”

Indeed, it is also often akin to knocking your head against open doors. It is one of the loneliest pursuits but the joy and relief of having written is indescribable.

To get to the point of completion in an as-yet-unfinished journey, Ferguson travels along seemingly convoluted obstacle courses through which she entwines a short history of many things, both personal and global. Of the former, for example, there is her ongoing preoccupation with suicide, whether doing it a la Virginia Woolf or Sylvia Plath — two of her literary heroines — or plummeting, while in the throes of full-blown junkiedom, into the abyss of the circular pit of Ponte in Hillbrow with it’s sordid neons winking and beckoning seductively. Of the latter, there’s the spurious War on Drugs, the malefices and myths woven by politicians, profiteers and power mongers. She notes Big Pharma who are culpable for the opiate epidemic, yet complicit in the classification of natural, non-addictive psychotropics such as ayahuasca, ibogaine and psilocybin alongside narcotics like cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine.

She also provides her take on the pandemic, in which conspiracy theories and wars abound across the sewers of social media, spouted between Q-tube armchair revolutionaries and their “thought control” enemies. She tries to make sense this “unbrave new world”, to deconstruct the bullshit botoxed as fact from both sides, the parallel realities, the cover-ups and carnage.

But her lockdown room with a view is from the admittedly cloistered perspective of privilege. Like everyone, she is nostalgic for life BC (Before Covid) apprehensive about the world AD (After Dystopia), aware of the gaping iniquities magnified by the pandemic, and numbed by the atrophying effects of reality television and online streaming services. But she remains isolated from the realities of life during the Plague, unlike those operating food kitchens for young and old alike, uniting across neighbourhoods usually separated by race and class. On the frontlines, the focus of healthcare workers and activists is not on the “whodunnit”. Instead it is on mitigating the suffering and telling the stories of despair, disease, death and hope; in hospitals and in impoverished communities where the concept of social distancing for a family of 10 in a shack is a luxury only the elite can afford.

The myrrh for Ferguson’s still bruised and increasingly anxious psyche is to find a haven, far from the madness of the masked masses: a luxury cabin in a remote gated nature reserve along the Matroosberg of Tulbagh. Her search for sanctuary is shattered by the murder of one neighbour and the robbery of another. The crimes remain unsolved, but they serve to further rupture unhealed sores that continue to suppurate beneath her skin.

Her surgical and “rebirthing” procedure is unconventional and controversial. Through her trajectory into the realm of psychedelics, Ferguson delicately peels away the scabs. After conducting research, she perceives them as a gateway to altered states of consciousness and healing, specifically through psilocybin, commonly known as magic mushrooms. Although still illegal, in controlled doses and environments, psilocybin, ayahuasca and ibogaine have been endorsed by psychologists and scientists alike, not only in treating addiction, opiate withdrawal and trauma but in providing a life-changing spiritual experience.

For Ferguson, the “shroom journey” initially opens the portal to a kaleidoscope of joy, of liberated consciousness. But subsequent trips entail revisiting the horror of being pistol-whipped and gang raped; of selling her body and soul for a hit, her fractious relationships with family, her failure as a mother and the years when crack cocaine and heroin were her lovers for which she constantly craved, carpet crawling like a crippled tiger in search of an elusive dragon. These are painful journeys, awash with tears, regret, and remorse; but also, cathartic.

Yet this perception of altering (or opening) states of consciousness through psychotropics remains controversially taboo for addicts in recovery. Ferguson runs the risk of the security blanket of Narcotics Anonymous being wrenched from her shoulders, of judgement by her peers power-mongers of jeopardising years of abstention and her status as “the poster child of sobriety”. But she takes the courageous decision to own her journey and disclose its process. In so doing she “births” a new self-understanding.

There is also the discovery of love at first Tinder swipe, in the form of her “Soul-Mat” with whom she remains; and the adoption of her fur child, Joe – to whom she becomes the mother she could never be to her biological children.

Wry, dry, self-deprecatory, lyrical, sometimes disarmingly inchoate and penned with unflinching candour, Ferguson’s quest, although incomplete, has reached a coda of sorts. The signpost at the end of this odyssey of slaying dragons with hallucinogenic clarity says that life doesn’t have to stop being hard in order to find happiness, healing and love.

Bamboozled is published by Melinda Ferguson Books, R320.