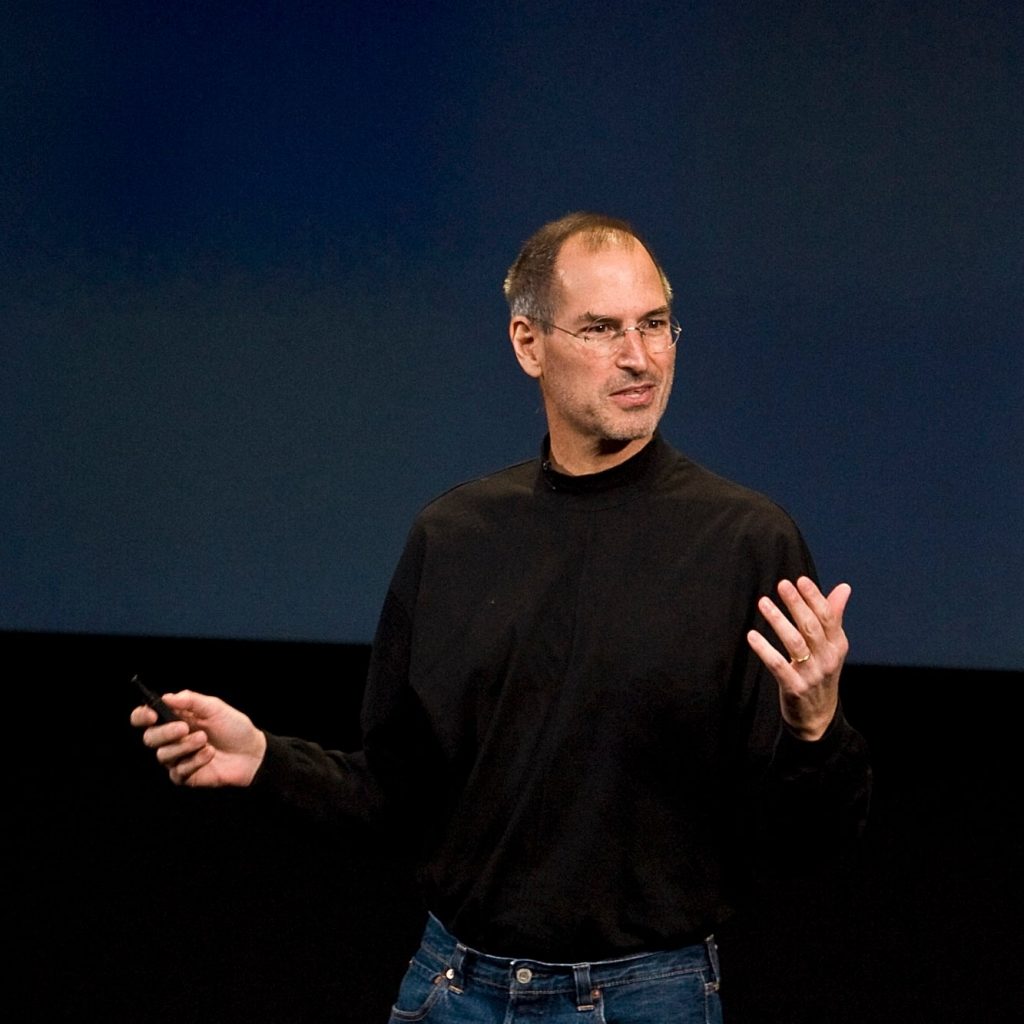

Petulant, impatient, perfectionist: Steve Jobs began Apple in 1976 with Steve Wozniak. He left the company for about 12 years but returned to

rescue it in 1997. Jobs died in 2011 but the company, under Tim Cook, continues to flourish.

The life of Steve Jobs was punctuated with milestones and iMacs. This year marks the 12th since the Apple co-founder and chief executive died of pancreatic cancer, at the age of 56, as well as 25 years of the iMac.

Jobs is synonymous with Apple, and Apple with Jobs. Even more than a decade after his death, it is difficult to dissociate the lore of two entities from each other. There is still a page on Apple’s website called “Remembering Steve”, where fans, friends and colleagues can post messages, with new ones popping up every few seconds.

But the magic of Apple lies in how its products — plus Jobs’s “product over profit” mindset — changed the way we live, work and play in such a seamless way, almost as if part of the natural evolution of the anthropocene.

Jobs famously described a computer as a “bicycle for the mind, a fabulous machine that could turn the muscle power of a single person into the ability to traverse a mountain in a day”.

His way of thinking, and personality-infused leadership style, overshadowed his reputation as an asshole. Tales from within Apple’s walls speak of his blatancy and daily petulance. He is said to have thrown an iPod prototype into an office aquarium in a fit of pique because it was “too big”.

In today’s world, where tech founders and billionaires can fall from grace, because of fraud exposés and where genius is replaced with greed-is-good capitalism, would Jobs’s tyrannical leadership style have had an effect on Apple’s current $2.4 trillion market cap?

Mark Zuckerberg is no longer seen as Facebook’s (now Meta) Harvard boy genius, but a weird narcissistic accomplice to political chaos. And Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter proves to users that tech chief executives might not be smarter than us mere mortals, what with the wacky tone-deaf tweets and mass lay-offs.

Elizabeth Holmes, who modelled herself on Jobs and was once hailed as the most important woman in Silicon Valley, has been sentenced to 11 years in prison for fraud.

But long after Jobs’s personality is forgotten, history will remember the technology his imagination conjured up, which permanently changed the personal tech, retail and digital publishing industries and how we consume music.

Rescued: The iMac G3 is seen

as ‘the computer that saved

Apple’. It was cheaper and linked to the internet.

Rescued: The iMac G3 is seen

as ‘the computer that saved

Apple’. It was cheaper and linked to the internet.

From footnote to force

It is believed Jobs was born Abdul Lateef Jandali before he was put up for adoption by his Syrian-born father and Swiss-German mother. A year later, he was adopted by Americans Paul and Clara Jobs, who assured his birth parents he would receive a university education, writes Walter Isaacson in the 2011 biography Steve Jobs. As Jobs’s longtime biographer, Isaacson was shown his most intimate personal and professional sides, both the good and the ugly.

Jobs and his partner Steve Wozniak started Apple in his parents’ garage in 1976. He was ousted from the company in 1985, in an internal power struggle.

But Jobs swiftly returned to rescue Apple in 1997 when it was “90 days from bankruptcy” after the business lost $1 billion because of failing non-computer products.

In retrospect, Jobs’s comeback to Apple cemented Apple’s comeback in the tech world. If he’d stayed away, his exit from the company he started would have made him a mere chapter in the business’s history, but his return proved that Jobs was Apple’s main driving force.

When he returned to Apple, Jobs eliminated 70% of products because he thought it was too confusing to have different variations at different retailers. Twenty years later customers are still benefiting from the simpler mix, with Apple’s better focus and quicker releases and upgrades than its competitors.

After his 1985 exit, Jobs started NeXT, another computer company, which was his ticket back to Apple. Apple bought NeXT in 1997. Jobs remained Apple’s chief executive until his death in 2011.

“The essence of Jobs is that his personality was integral to his way of doing business,” Isaacson writes in the Harvard Business Review.

“He acted as if the normal rules didn’t apply to him, and the passion, intensity, and extreme emotionalism he brought to everyday life were things he also poured into the products he made. His petulance and impatience were part and parcel of his perfectionism.”

Isaacson once asked Jobs about his famed viciousness in meetings. “These are all smart people I work with, and any of them could get a top job at another place if they were truly feeling brutalised. But they don’t […] And we got some amazing things done,” Jobs told him.

Isaacson writes about Jobs’s screaming match with Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, as well as with Android’s chief, Andy Rubin, after feeling “betrayed” by the duo. They had made their own move into the smartphone space with Android-powered Google smartphones, instead of Apple’s, prompting Apple to file a vicious lawsuit.

Although Jobs took Google’s move personally, he also realised the importance of making friends with its largest competitor, Microsoft. Through a $150 million investment, Apple acknowledged it didn’t have to compete with Microsoft.

Apple’s “Get a Mac” ad series, starring Justin Long as personified Mac and John Hodgman as a PC, which ran from 2006 to 2009, spoke to this truce and set a new bar for humour in advertising.

Jobs’s last words were, “Oh wow. Oh wow. Oh wow,” says Isaacson.

His live fast, die young lifestyle leads to the question of whether his brilliance contributed to his death.

From Apple II to iPhone 14

Apple’s most successful products can be measured by their innovation and how many units they sell worldwide. As of this year, more than 2.24 billion iPhones have been sold.

Taking into account the different versions of each gadget and accessory, including discontinued products, Apple has released more than 200 products since 1976.

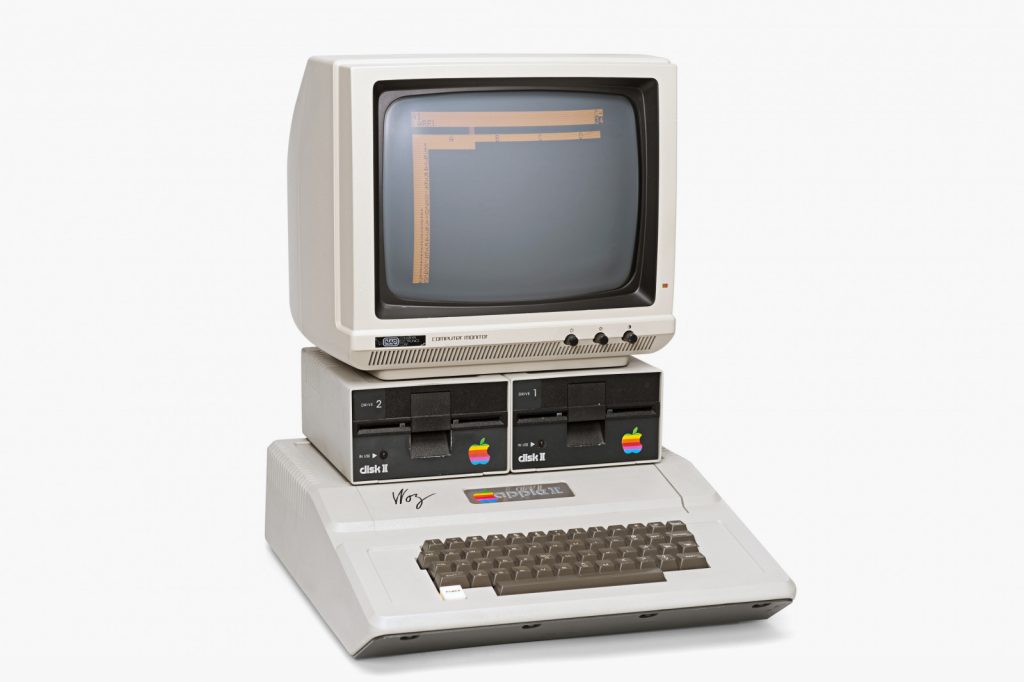

In 1976, Apple’s first product was a motherboard-style computer, the Apple I, which was handmade by Wozniak. Isaacson writes that the name “Apple” stemmed from Jobs’s stint as a fruitarian.

“He had just come back from an apple farm, and thought the name sounded fun, spirited, and not intimidating,” Isaacson recalls.

Then: A vintage 1970’s Apple II 8-bit home computer, with the signature of Apple designer Steve Wozniak on the main unit, taken on May 21, 2009. (Photo by Mark Madeo/Future via Getty Images)

Then: A vintage 1970’s Apple II 8-bit home computer, with the signature of Apple designer Steve Wozniak on the main unit, taken on May 21, 2009. (Photo by Mark Madeo/Future via Getty Images)

The success of Apple II, which was released in 1976 as a personal computer, was due to a spreadsheet application favoured by the US’s business world. The Apple II was also the first of its computers with colour graphics.

By the end of that year, revenue was at $700 000 and it doubled every four months because of the spreadsheet application. By 1980, Apple II had taken revenue to $118 million.

The Apple empire was built on user-friendliness. Designers grapple with parallel imperatives — on one hand, making products desirable to the masses and, on the other, a responsibility to teach new technologies.

Jobs famously insisted on being able to get to whatever he wanted in three clicks.

“Jobs aimed for the simplicity that comes from conquering, rather than merely ignoring, complexity,” writes Isaacson. “Achieving this depth of simplicity, he realised, would produce a machine that felt as if it deferred to users in a friendly way, rather than challenging them.”

Jobs gave the green light to designs but head designer Jony Ive is the man behind some of Apple’s top products, such as the iPhone, iMac and iPad. The two would walk around, sometimes for an hour or two, just feeling the products, turning them over.

“Steve would say ‘This doesn’t feel right to me’ or ‘This is beautiful but let’s make it with a touch screen and do it this way.’ It would let him focus … on the sweep of future products they had and what they would look like and whether they would be beautiful,” writes Isaacson.

Now: Apple’s latest phone, the iPhone 14. (Jeenah Moon/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Now: Apple’s latest phone, the iPhone 14. (Jeenah Moon/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Apple after Jobs

Since Tim Cook succeeded Jobs as Apple’s chief executive in 2011, it’s hard to keep up with every iPhone launch. Apple’s major moneymaker, the iPhone, was launched in 2007 and 16 years later the iPhone 14 is the latest flagship model, sporting too-hot-to-handle tools, a ridiculous number of cameras and a sense of Jobs’s brilliance. As of the first quarter of this year, revenue is already at $117.2 billion.

Today, Apple’s announcements are held at Apple Park in California. A ring-shaped infinity loop is the crown jewel of a trillion-dollar empire built upon iPods, iMacs, iPads, Apple Watches and iPhones, devices that, despite being some of the most advanced computers ever made, are simple to operate.

“If the building looks like a spaceship, then it’s one that lifted off directly from Steve Jobs’s imagination to land in the heart of an otherwise sleepy suburb. It was one of the last undertakings that the great man signed off on before he died,” write authors Cliff Kuang and Robert Fabricant in User Friendly: How the Hidden Rules of Design are Changing the Way We Live, Work and Play.

Apple unveiled four new iPhones, three new Apple Watches and an updated AirPods Pro during a press event last year at Apple Park. (Photo by Mustafa Seven/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Apple unveiled four new iPhones, three new Apple Watches and an updated AirPods Pro during a press event last year at Apple Park. (Photo by Mustafa Seven/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Jobs first told of Apple Park in 2006 during a keynote address, when he referred to it as “the spaceship” and “the ring”. Today, Apple Park houses the largest curved glass panes in the world at 13m high and four storeys tall. The Apple auditorium, also known as the Steve Jobs theatre, seats 1 000 guests.

With the meteoric success of Apple, it’s hard to fathom the pressure felt by Jobs and his team. Customers rarely switch out of the Apple ecosystem regardless of “Apple tax”, the premium added to the price, simply because it’s an Apple product.

Jobs, like his products, was a walking juxtaposition. He was controlling, but driven by his passion for perfection and making elegant products. His products are simple but house some of the world’s most beautifully complex systems.