Mad about music: Sudanese musician Jantra, whose name translates as “craziness”, with his trusty blue Yamaha keyboard, playing at a party in DarGoog in Sudan recently. His album Synthesized Sudan was released by Ostinato Records earlier this year. Photo: Janto Koité/Ostinato Records

In a small, but prominent, part of the music industry,

a number of record labels release music from Africa but outside the mainstream. Issued mostly on vinyl, it is music from the continent’s rich past, or current sounds not commercialised or autotuned for Western ears. Most of the people involved do it as a label of love (pun intended) because sales are never spectacular. The best of these labels do it with extensive, well-researched sleeve notes, proper contracts with the artists or, if they are no longer around, their families, and with deep knowledge and love for the music. Fan and collector Charles Leonard spoke to four of them about some of Africa’s finest musical treasures

Vik Sohonie – Ostinato Records

Ostinato Records started in 2016 to combine storytelling, history, and music to transform our understanding of and perspective on lesser-known cultures, and in doing so, reorient our notions of centrality in history and where the best music comes from.

What are you specialising in?

We specialise in unearthing new styles/genres/sounds of music from lesser-travelled parts of the world, especially misunderstood parts of the world, such as Somalia, Sudan, and Haiti.

What is the typical record you release?

We’ve released a wide array of records from across the Caribbean, and Africa, and we are now focusing on Asia.

The similar thread that runs through all our records is simply a sound that people have come to identify as Ostinato’s brand — even if the genres, styles, bands are so different.

We’ve released compilations, or historic music, as well as contemporary sounds.

Who is your typical buyer?

I would think of our record label as an international food court. People who go to such places differ.

Some are adventurous and like to try everything there is. Some like only a handful of cuisines, and are loyal to those, and some will stick to one food stall and only eat what they have to cook up.

So, that’s to say, we have our loyal fanbase, we have people who dabble in some styles specifically, and we have people who only come when a certain country/ style is put out.

How do you source your records?

For our historical compilations, we exclusively rely on public and private archives. But we never remove the original master material from the country, as those are historic artefacts that belong in the country, and are not circulating in European auctions.

We use digitisation methods and strike deals with the archives that benefit both parties, such as leaving behind the digitisation equipment so the archive can continue digitising their national heritage in high quality after we are gone.

Why are you doing it?

I see it as a mission — we have altered the universe ever just slightly by putting out these records and informing a global audience to look beyond where they would think great music is made, and in doing so, change their perception of the world.

We are doing it to combat the greatest plague of all — Western-centric notions of the world.

How important are sleeve notes?

Sleeve notes are crucial because you must treat the music and history with respect. They are effectively journalistic endeavours filled with interviews, history, perspectives that have not been aired prior.

What should be in them is information that simply has not been published before. We will never release a record with original notes; we will always write our own.

Why are African reissues important here, in 2023, in our world?

I believe the African reissue market has diminished substantially. It has been saturated and too many reissues exist on the market. This is the natural course of affairs.

I doubt any record label putting out African reissues today is seeing the same sales that existed six to seven years ago.

Now that the historic has been introduced to the world thoroughly, it is time to focus on the contemporary underground in Africa, in our opinion, as we have done with Jantra’s Synthesized Sudan.

Do you contribute to making a better world in any way?

If we have changed even one person’s perspective about a country, elevated a country’s image, or got just one person to see history differently — i.e., the West is not the centre of everything — that makes the world a better place.

What has been your best-selling record and why?

Sweet as Broken Dates, our Grammy-nominated compilation. Music aside, I think simply because it was so counter-intuitive to people’s perceptions of Somalia that it simply blew people’s minds and captured everyone’s imagination.

What have you got planned for the foreseeable future?

We just returned from central Asia and are working on a compilation of the region via a Soviet-era archive.

Will the African reissue market continue to grow?

I think it is diminishing, not growing. African music has flooded the global music market in the last few years and now the challenge is finding the next region of the world that will make serious gains.

I believe the answer lies in the “Arab world” and Asia.

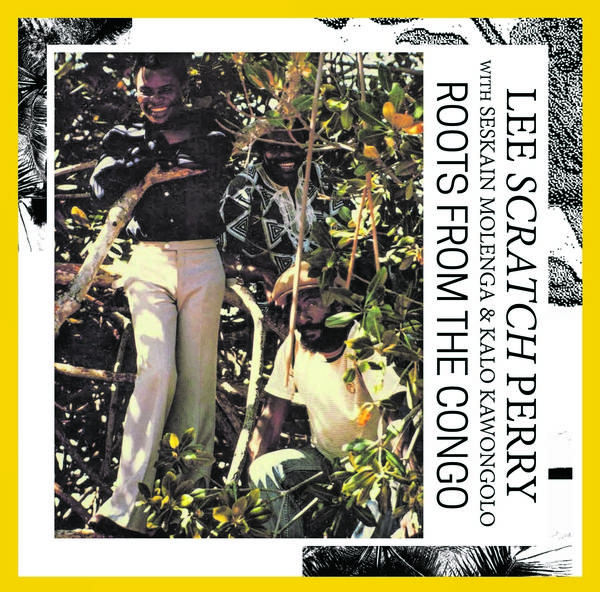

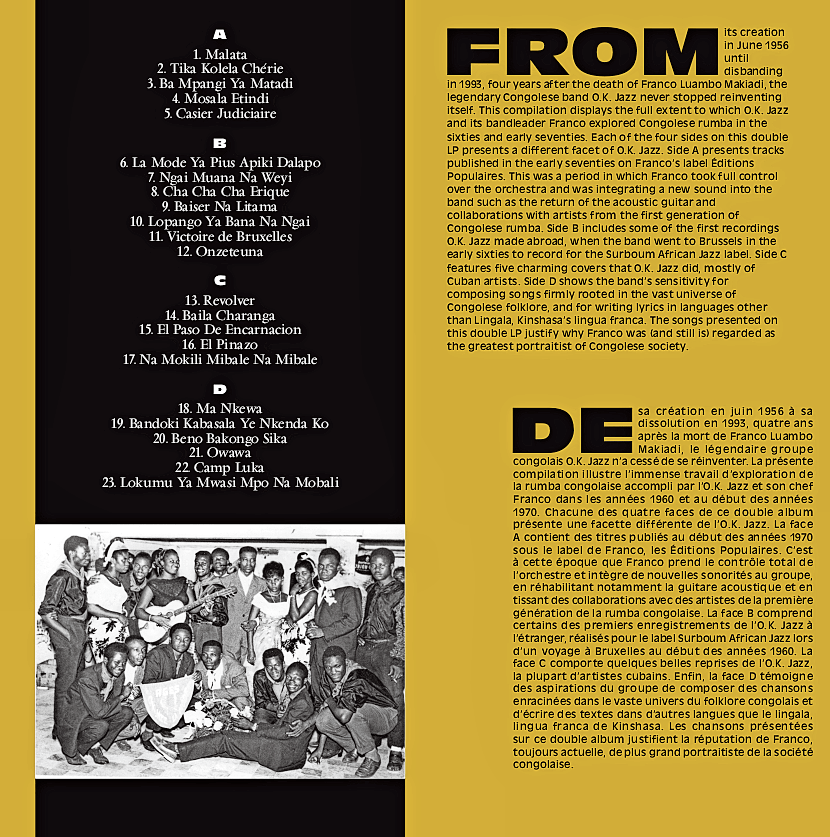

Mission: The legendary Congolese guitar player and band leader Docteur Nico’s double compilation vinyl album God of the Guitar (above), which was released in 2017 by Planet Ilunga. Above and right, other releases by the independent record label from Brussels, Belgium, which archives, documents and puts out early Congolese popular music.

Mission: The legendary Congolese guitar player and band leader Docteur Nico’s double compilation vinyl album God of the Guitar (above), which was released in 2017 by Planet Ilunga. Above and right, other releases by the independent record label from Brussels, Belgium, which archives, documents and puts out early Congolese popular music.

Bart Cattaert – Planet Ilunga

Planet Ilunga is an independent Brussels, Belgium-based record label, dedicated to the archiving, documenting and sharing of early Congolese popular music.

Until now, the focus was on the period 1950 to 1970 — on famous Congolese musicians like Franco Luambo, Joseph Kabasele, Docteur Nico, Vicky Longomba, bands like African Jazz, OK Jazz, Rock-a-Mambo, African Fiesta Sukisa or labels such as Ngoma, Loningisa, Esengo, Surboum African Jazz.

When did you start?

I started the label in 2013 and 10 years later the catalogue consists of a total of 281 reissued songs. Planet Ilunga is mostly a vinyl label.

What is the typical record you would release?

The scale of the early Congolese music scene is very large, with thousands of songs. It’s very tempting to go for a cherry-picking approach, and compile mixed albums with the best songs of different artists, periods, labels and genres, but my approach is rather thematic.

In general, it takes a couple of years to finish a release because I need to collect a lot of information, such as records, lyrics, photos and I have to licence the rights with the families.

I deal directly with the families of the artists and label owners. I also put them in contact with other initiatives in the film and cultural world.

Who is your typical buyer?

Young and old, I would say. The records are mostly sold in Western Europe, Japan, US, UK, Greece. Not as much in Africa as I would like.

A shop in Luanda [Angola] is stocking the albums and they also find their way to the two Congos through a friend who distributes them on a small scale and through other collaborators.

How do you source your records?

The few existing professional archives of early Congolese modern music are far from complete or not always easily accessible, so I’m sourcing the records mostly from private collections or my own collection. Thanks to those collectors we can listen to the origins of modern Congolese music.

Every compilation, and especially the larger ones, is a collaboration with different collectors and experts.

Why are you doing it?

Because I feel there is a need to document this archive. The Congolese people simply have one of the world’s most interesting musical heritages and so much of it is forgotten or lost.

How important are sleeve notes?

They are as important as the sounds. My main goal with this label is to provide the context and the stories of the early labels and artists.

Also, I try to interview a lot of elder Congolese people and publish those interviews as testimonials. They give a more intimate feeling to the stories.

I pay attention to the lyrics as well. It depends on the project and the space in the booklet but, ideally, we give the transcription and translation of the songs.

I don’t think I will release records with the original notes, simply because on the original releases, there was little or no info to be found.

What has been your best-selling record?

Our reissue of a 1979 album that Lee “Scratch” Perry made with Seskain Molenga and Kalo Kawongolo, two Congolese musicians. From the Congolese rumba records, the Docteur Nico and different OK Jazz compilations sold out pretty quickly.

What have you got planned for the foreseeable future?

Next up is a release about Franco Luambo Makiadi and his label Les Editions Populaires.

What is the biggest challenge that you face?

Finding well-preserved records and digitising them. I hope one day a museum, government or institution takes up this role.

Today, it is mainly thanks to small-scale initiatives around the world that some of the songs made in the fifties and sixties can still be heard.

If properly archived, they could be a treasure trove of Congolese culture, and perhaps a source of inspiration for the current generations.

Will the African reissue market continue to grow?

I’m not sure if this market grows. But I noticed it has been more diversified with smaller and, important, locally established labels and thus more original projects.

In the seventies and eighties, the ethnographic approach was in vogue but that is mostly gone.

In the 2000s, the well-known labels mostly focused on the Afrobeat genre. There were a few excellent releases but it was too much the same. Also, a lot of Ethiopian seventies music has been reissued now.

The last couple of years, I also noticed a growth in reissues in South African 1970s music, classic Egyptian and other North African music and in 1980s Rai music from Algeria.

Some international record labels now shift more and more to electronic music coming from the African continent where a lot of the music made in the eighties was only released on cassette format. I expect this to grow in the following years.

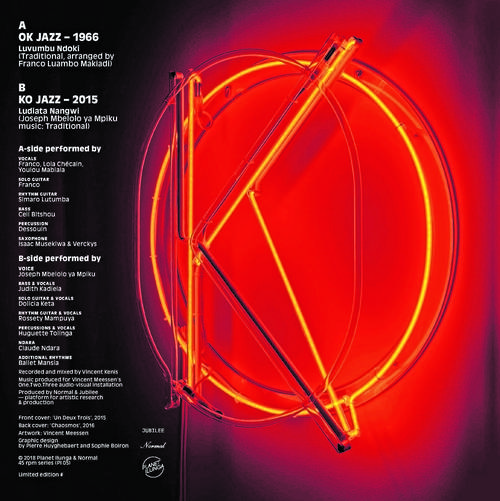

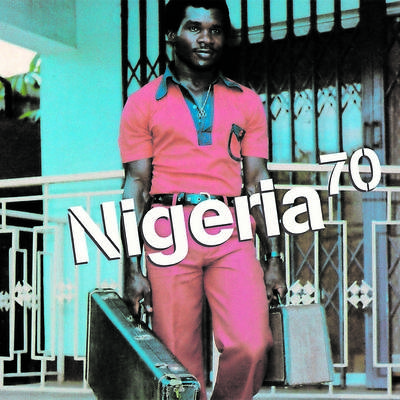

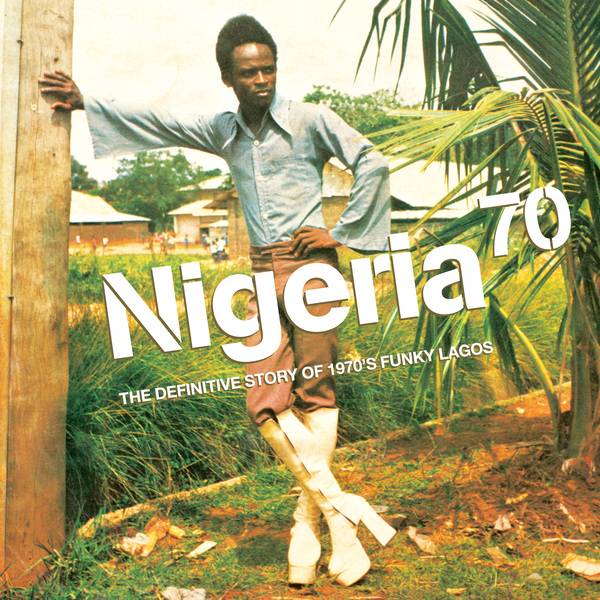

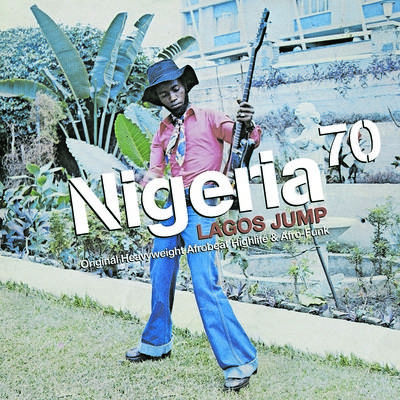

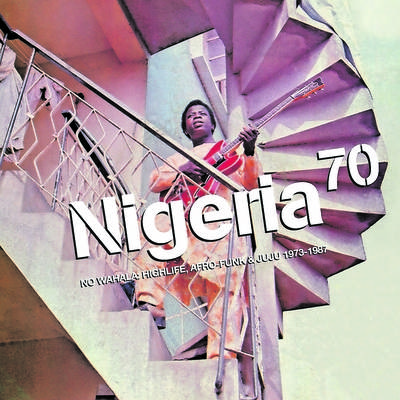

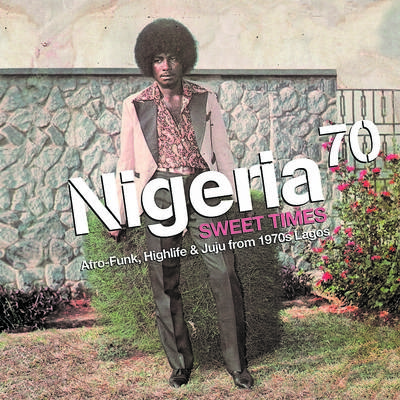

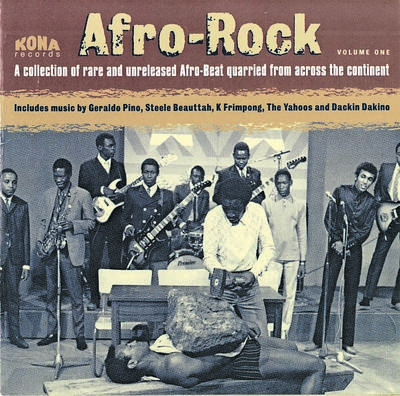

Strut your stuff: Albums from Strut Records, which releases the work of new artists, compilations and original album reissues.

Strut your stuff: Albums from Strut Records, which releases the work of new artists, compilations and original album reissues.

Quinton Scott – Strut Records

Strut’s vision was originally to document the history of dance music and unheralded music in the field of jazz, soul, African and Latin music.

We have since worked with young artists and original music legends to record new albums and tour again so our work now is a mix of new artist albums, compilations and original album reissues.

What are you specialising in?

The music on the label over the years is very wide genre-wise, spanning Afrobeat, highlife and Ethio-jazz to disco and post-punk, all loosely related to club culture.

I started the label in 1999 and it was sold to the German label group !K7 in 2007.

What is the typical record you would release?

I don’t think there is a typical record, since the range is so wide, but we do put a lot of work into keeping the quality high each time — great mastering, good-quality packaging, liner notes and artwork.

So, people know that, if they buy one of our albums, it will always feature great music and there will be a lot of love and care put into it.

Who is your typical buyer?

We have a wide range of buyers from younger vinyl fans to older music heads who have followed the label on and off over the years.

Our audience is probably weighted heavily towards male buyers, so I think we definitely need to do more to attract female music fans and DJs.

How do you source your records?

We work with a lot of DJs and collectors and, since we have been established for so long, we are lucky in that we get approached with many amazing projects.

We have certain people we have worked with since the start who are very much part of the label’s core team — collector Duncan Brooker, for instance, compiled our Nigeria 70 and Next Stop Soweto series and we are always hatching projects with him.

Why are you doing it?

A question I ask myself most days! I think any label like ours is doing it to make available great lost music, so that it is there to enjoy now and for future generations.

It is also about telling the artists’ stories and helping to create the legacy that they deserve, as well as seeing them get paid fairly for their music.

It is incredibly rewarding to see artists like Ethio-jazz pioneer Mulatu Astatke gain long-overdue worldwide recognition in recent years, for instance.

How important are sleeve notes? What should be in them? Would you ever release a record with just the original notes?

I think they are really important —much of the time, lesser-known artists didn’t ever get their story told and they all have amazing stories, every one of them.

So, I think it gives vital context to the music and, for the music fan, they get a feel for the personalities behind the record.

It is rare that we release a record without new liner notes.

Why are African reissues important here in 2023 in our world?

I think African music was under-appreciated outside of the continent for far too long.

The period during the 1980s and early 1990s of so-called “world music” definitely helped awareness a lot in the West but often presented the artists in a slightly sterile way with ultra-clean productions.

Since the renewed interest in African music since the early 2000s, I think Western audiences have embraced the music much more widely and it is now part of people’s playlists among soul, pop and any other style.

I think the only drawback is the focus has been on funkier “rare grooves”, so many people may know William Onyeabor and Batsumi, say, more than the greats like Franco, King Sunny Ade or Mahotella Queens.

So, there is still a lot of work to do and so much really incredible African music for people yet to discover.

Do you contribute to making a better world in any way?

Yes, many people have said that music is a positive and healing force and I think it works on many levels — from the artists’ side, they get paid and get recognition and different music touches people individually and deeply, in its own way, and collectively through concerts and clubs.

Lyrics too can resonate through the years — life stories, political commentaries or messages of love and peace.

Music is a universal joy which can touch anyone, anywhere and should never be under-estimated as a force for good.

What has been your best-selling record and why?

We were very lucky to acquire Patrice Rushen’s Elektra catalogue a few years ago, including her hits Forget Me Nots and Haven’t You Heard, and the reaction to our reissues was incredible.

I think her music has endless appeal – it is beautifully written, produced and arranged and she is very unique and intricate in her sound, influencing many younger artists over the years.

What have you got planned for the foreseeable future?

Next year is our 25th anniversary, so we are celebrating with some events and special releases.

We have two major reissue projects from Sun Ra, a new studio album by UK soul/jazz band Nubiyan Twist and two great compilations by Ugandan DJ Kampire and Colombian DJ Edna Martinez.

What is your biggest challenge?

There are many pressures — streaming and the digital market has made compilations much more difficult as many people just make a playlist rather than buy an album.

Vinyl prices have been very high in the last two years which has made the climate very difficult. And it is a very competitive market with different labels involved in reissues. But, with the right album and strong PR and marketing, sales can still be healthy.

Will the African reissue market continue to grow?

I think there was a saturation point a few years ago when over 100 labels worldwide were involved in reissuing African and global music.

It has settled down over the last two to three years, as the market has become harder, but there are still vast archives of under-appreciated music and many great labels around, so I am sure the interest in, and appreciation of, great African music from yesteryear will continue onwards.

Heavenly: Mississippi Records has made Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam

Guèbrou’s solo piano works from the 1960s available again. She was an Ethiopian nun, composer and musician, who died this year at the age of 99.

Heavenly: Mississippi Records has made Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam

Guèbrou’s solo piano works from the 1960s available again. She was an Ethiopian nun, composer and musician, who died this year at the age of 99.

Cyrus Moussavi – Mississippi Records

Depending on who you ask, Mississippi Records has been around for 20 years, as of 2023. A rotating cast of characters has contributed release ideas, art, sound and sweat.

We work directly with artists and their families. We release “discarded music of the world”, according to one of our dear friends and mentors, Lonnie Holley.

Why are African reissues important here in 2023 in our world?

We don’t just do African reissues. We research and release overlooked music from all over the world.

Why is it important now? Because we’re living in a time of utter madness and loneliness and spiritual emptiness and it’s important to have examples of humanity and light to look to.

You’re not going to find the feelings expressed in this music online. Our hope is these physical objects force people to spend time together and reflect on the lives of true artists who created, despite a lack of financial success or critical acclaim, felt compelled to express something deep within themselves, and left us with searing and undeniable proof of the possibility for beauty amid darkness.

Will the African reissue market continue to grow?

I have no idea; I’m sickened by the idea of an African reissue market! I hate that we have to sell these objects.

What made you decide to release Hypnotic Guitar of John Ondolo?

The song Tumshukuru Mungu kept me going at a very difficult time in my life. When we got the chance to meet Ondolo’s daughter, Perpetua, in Tanzania, and work with the great music historian and researcher John Kitime, we didn’t hesitate.

It’s a dream to make this music available to more people after hearing it repeat over and over in my head for so many years.