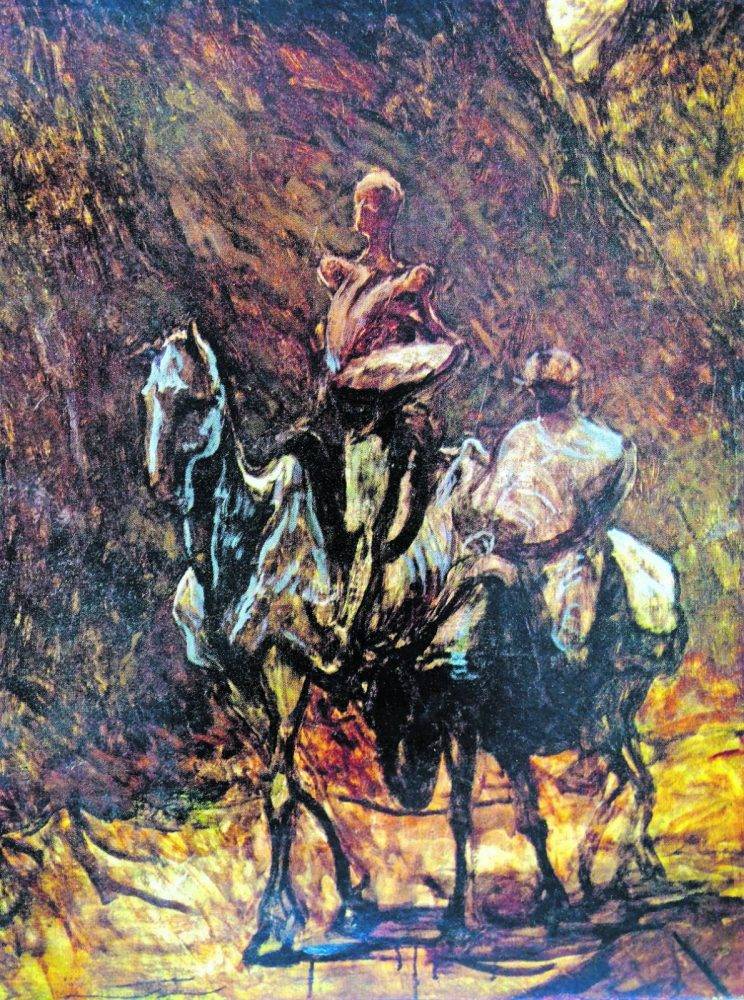

A painting of Don Quixote, the protagonist of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra’s novel, and his companion Sancho Panza, by French painter Honore Daumier from the late 19th century. (VCG Wilson/Getty Image)

And so we come to the Everest of novels, both the parent of the modern Western literary canon and the text that prefigures all those that followed its publication in 1605 and 1615. But two parts, two books? Yes — the first of many surprises that await those making the acquaintance of Miguel de Cervantes’ übertext Don Quixote.

First, make that Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, “almost certainly born in 1547”, according to one laconic source, showing due and proper scepticism for the facts attendant on the great writer’s life.

Where? In Tobias Smollett’s marvellously entertaining and judiciously speculative The Life of Cervantes that prefaces his 1755 translation of the novel, the reader is offered: “One author [Thomas Tamayo de Vargas] says he was born at Esquivias; but offers no argument in support of his assertion … Others affirm he first drew breath in Lucena, grounding their opinion on a vague tradition which there prevails: and a third set [Don Nicholas Antonio] take it for granted that he was a native of Seville, because there are families in that city known by the names of Cervantes and Saavedra; and our author mentions his having, in his early youth, seen plays acted by Lope Rueda, who was a Sevilian.”

With the benefit of a few extra centuries of Cervantine scholarship, The Oxford Companion to English Literature (sic!) sweeps away Smollett’s delightful, informed conjecture and declares: “Born in Alcalá de Henares of an ancient but impoverished family”.

The biographers agree on the straitened circumstances of Cervantes’ family life, his father universally described as a down-and-out surgeon. Worse awaited Miguel. He enlisted in the army, fought at the great Battle of Lepanto in 1571, when Don John of Austria led a coalition fleet from Christian states to a decisive and history-changing victory over the Turkish navy. Severely wounded, Cervantes lost the use of his left hand.

Four years later, returning to Spain, he was captured by a “Barbary corsair” and sold as a slave to a “Moor” in Algiers (Smollett’s version); modern sources reckon his master was a “renegade Greek”. Whichever, Cervantes tried to escape several times until, mercifully, he was ransomed and made it home at last to Spain in 1580.

For the next 36 years, earning a living worried at Cervantes in much the same way that Herman Melville was to struggle to make ends meet. Tragically, their masterpieces Don Quixote and Moby-Dick granted them literary immortality but not daily wherewithal.

Cervantes, Melville and Joseph Conrad led adventurous, sea-faring lives before beginning literary careers. Their time before the mast hugely benefited their writing, some of which took place under the least prepossessing of circumstances. In Cervantes’ case, as he hints in the preface or prologue to the first volume of Don Quixote, in jail.

“And to what can my barren and ill-cultivated mind give birth except the history of a dry, shrivelled child, whimsical and full of extravagant fancies that nobody else has ever imagined — a child born, after all, in prison, where every discomfort has its seat and every dismal sound its habitation?” (John Rutherford’s wise and witty translation for Penguin Classics, 2000.)

Translation is a vexing aspect of reading Quixote. To begin, take its full title. Smollett gives us The History and Adventures of the Renowned Don Quixote; Rutherford offers The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha and the much-hyped Edith Grossman version (2003) is The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha.

Even more illuminating of the translators’ approaches and styles is the way they render the novel’s famous opening line.

Smollett: “In a certain corner of La Mancha, the name of which I do not choose to remember, there lately lived one of those country gentlemen, who adorn their halls with a rusty lance and worm-eaten target [shield], and ride forth on the skeleton of a horse to course with a sort of a starved greyhound.”

Rutherford: “In a village in La Mancha, the name of which I cannot quite recall, there lived not long ago one of those country gentlemen or hidalgos who keep a lance in a rack, an ancient leather shield, a scrawny hack and a greyhound for coursing.”

Grossman: “Somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember, a gentleman lived not long ago, one of those who has a lance and ancient shield on a shelf and keeps a skinny nag and a greyhound for racing.”

It was JM Cohen’s conscientious translation (1950) for the Penguin Classics that introduced me to Don Quixote (real name: Alonso Quixano or perhaps Quixada, Quesada or Quexana!). The aged country squire, his mind beguiled and addled by reading too many chivalric and pastoral romances, decides to become a knight errant himself and sets off on adventures of his own.

So it is that the reader becomes closely acquainted with his old horse Rocinante, travelling and conversational companion Sancho Panza, Quixote’s beloved Dulcinea del Toboso, Sancho’s long-suffering wife Teresa, and a score of other characters, objects, places and happenings. These include bachelor Sansón Carrasco, the wicked men from Yanguas, the barber, the helmet of Mambrino, the fighting windmills, the village priest, the Parliament of Death, the Cave of Montesinos, the island of which Sancho became governor (yes!) and the fabulous Cide Hamete Benengeli, the real author of the book — about whom more below.

A painting of Don Quixote, the protagonist of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra’s novel, and his companion Sancho Panza, by French painter Honore Daumier from the late 19th century. (Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

A painting of Don Quixote, the protagonist of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra’s novel, and his companion Sancho Panza, by French painter Honore Daumier from the late 19th century. (Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

After Cohen’s rendering came the revelation of Smollett’s fluent and vivacious translation, though one not without flaws and controversy. Even in Smollett’s day it was held he had no Spanish and had worked from a French translation or, worse, resorted freely to borrowing from the accurate rendering of the late painter Charles Jervas (also Jervis).

On the 200th anniversary of Smollett’s translation, Carmine Linsalata, a Stanford PhD, published his doctorate as Smollett’s Hoax, but not giving enough weight to his subject’s education as a surgeon with a good grounding in Latin, and hence a facility for romance languages.

Furthermore, Smollett was a great comic novelist. The influence of Don Quixote is evident in his riotous epistolary novel The Expedition of Humphry Clinker — note the dropped E in the protagonist’s first name — and so his translation is what the eminent Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes claimed: “… the one where the feeling and the tone both come through … the homage of a novelist to a novelist. It is a novelist’s translation.”

While the Grossman version seems to swerve from wit and humour at crucial points, serving up an austere comic-lite Quixote, Rutherford shows triumphantly there does not have to be a binary choice between stodgy accuracy and fluent vivacity.

Still, whichever translation you pick up, a feast awaits. No synopsis of this vast novel — 940 pages in most editions — is offered here. But some tips for reading might help.

One, the famous windmill scene occurs very early — chapter VIII in the first volume.

Two, do not be seduced by 19th century German Romantic readings of Don Quixote as the “Knight of the Woeful/ Sad Countenance” or “Sorrowful Face”. Smollett’s coolly ironic “Rueful Countenance” and, best of all, Rutherford’s “Knight of the Sorry Face” catch the Spanish humour and self-deprecation.

One needs to remember that Germany, despite being the self-appointed definer and arbiter of all things, most recently of genocide, can be wrong now and then.

Three, Cervantes’ novel is a masterclass in incisive, satirical literary criticism. He pokes fun at and fatally undermines certain genres, particularly exaggerated tales of chivalric heroism and the plays of his detested rival Lope Felix de Vega Carpio.

To achieve this, Cervantes interpolates his versions of stories from particular genres, the shepherd’s tale for instance, which illustrate his litcrit point but don’t necessarily advance the main narrative. These “intercalated” tales can be skipped but you might well enjoy them because they are superb examples of high send-up.

Four, you will fairly often be met with two facing pages of solid text, with no paragraph breaks. This is no printer’s error but the admirable result of the English text reflecting the Spanish’s discreción. Verbally, discreción is the ability to speak in paragraphs that while lengthy are also lucid, rhythmic and compelling. The written version is dazzling.

Five, Cervantes raises questions of authorship and invents “postmodernism” centuries before they were sparks in anyone’s imagination.

In volume one he reveals he is merely the link between the real author Cide Hamete Benengeli and the reader. There are playful clues and denials in that name, however: Cide is “My Lord”; Hamete is the Spanish for the Arabic name Hamed, “he who praises” and Benengeli is a wonderful comic creation, referencing berenjena, aubergine in Spanish, and sneaking in a connotation of brinjal-eater.

Cervantes shows in volume two Quixote and Sancho discovering their literary existence and celebrity in a bookshop. This also allows him to repudiate the “false Quixote” authored by one calling himself or herself Alonso Fernandez de Avellaneda, the appearance of whose outrageous rip-off no doubt encouraged Cervantes to write the second part of Don Quixote published in 1615.

Six, some say Cervantes died on the same day as William Shakespeare, 23 April 1616. Almost certainly?