Popo Molefe, Quiet Activists author Peter Present, Zac Yacoob and Brian Hermanus at a UDF rally.

On the morning of 8 June 1986, we received the message from Jane we were finally going home. We were once again unprepared and were not fully briefed for our next journey, our return home. We hurriedly said goodbye to our comrades and were rushed to the airport.

En route, Jane and Nkosi revealed that we would be flying to Botswana and had been booked into the Gaborone Sun Hotel. We were also given only $78 each to get us from Botswana to Cape Town. No clarity was provided as to why we needed to rush, and we had no discussions about our mission back home or who we needed to meet up with once we were in Cape Town.

Nkosi guided us through customs. In [my wife] Bibi’s bag there were still travellers’ cheques that we had not declared when we entered Zambia. I remembered the problem I had had with the bank in Botswana and knew that if they discovered them and realised that we had not declared them on arrival, we would be faced with a similar issue.

I quietly told Nkosi about the problem. Bibi handed her bag containing the cheques over to Nkosi and, once we were through customs, he then gave the bag to a customs official he knew. The official then promptly handed the bag back to Bibi without it being searched. This was a close call, but we were safe at last, ready to fly back to Botswana.

The airport at Francistown — a small town in the east of Botswana near the Zimbabwe border — was hot and stuffy, with no air conditioning to speak of. We hung around the airport for a few hours, waiting for our connecting flight to Gaborone.

It was only when we checked into the Gaborone Sun that we realised that the ANC had booked us into a rather expensive hotel, leaving us to settle the bill. Of course, we didn’t have enough money to pay for our Botswana accommodation as well as our return to Cape Town. The only thing that perhaps kept us from panicking was that by now we were back in regular contact with our families. At this point, we were still keeping up the travelling ruse with all our relatives except my father, and it was during a conversation with him that I told him about our financial predicament.

All Bibi and I could do was sit in our hotel room most of the day, only heading down to eat. We were very aware that the South African security establishment had agents in Botswana.

One afternoon, shortly after our arrival, the phone in our hotel room rang. Alarmed, Bibi and I turned to each other.

“Who can it be?” I wondered aloud … Nobody knew we were there. “Should we pick it up or just let it ring?” was Bibi’s response.

I picked up the receiver.

“Hoe gaan dit, Peter? Ek is hier by ontvangs,” the person on the end of the line said. “Kom asseblief af — ek wag hier vir jou.” (How are you, Peter? I’m here at reception — please come down.)

If ever my mind tried to make sense of a situation but failed, this was it. The Afrikaans spoken was fluent. It is definitely the person’s first language, I thought, but not a Cape Town or Johannesburg accent. This was the voice of a white person. Could it be that a member of the South African security establishment had tracked us down?

I must have been silent for a moment as I tried to make sense of it all. Bibi and I looked at each other as I asked, “Met wie praat ek?” (Who am I speaking to?) Having answered in Afrikaans, it was now Bibi’s turn to sport a blank look on her face.

“Kom af na ontvangs toe, dan gesels ons,” the individual replied. (Come down to reception then we can talk.)

With a curt “Okay”, I put down the phone.

I told Bibi what the person had said and she was equally convinced that we were now dealing with a member of the South African security establishment. But what could we do? He knew we were there … Our options included me going down alone, both of us heading downstairs, or leaving the hotel undetected. The last option would then mean we would be forced to find a place to hide out in Gaborone.

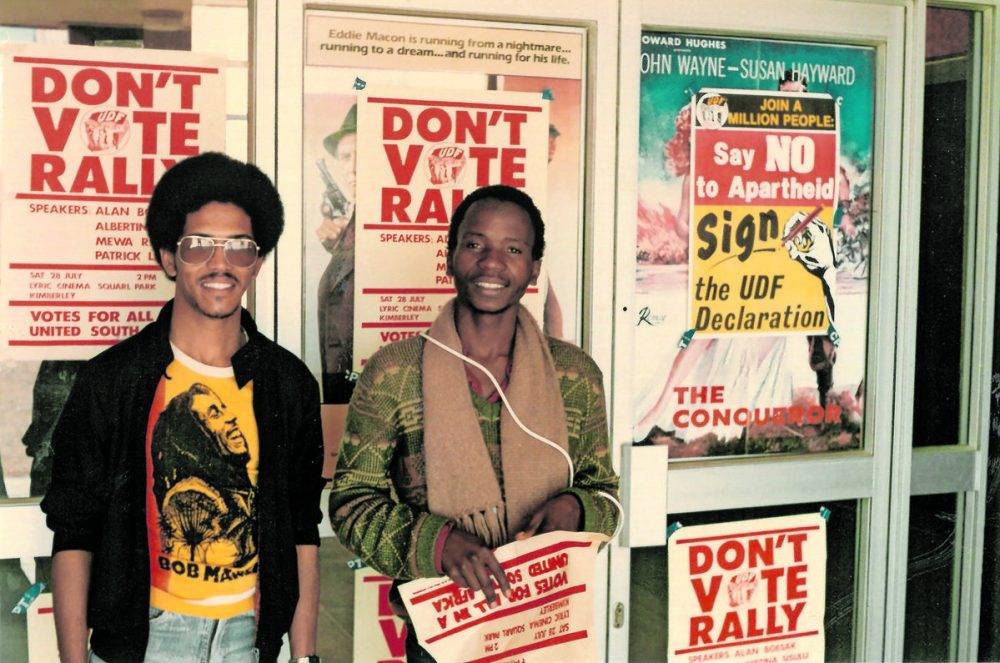

Present and his comrade Kwena Mothogoane put up posters in Kimberley before the author and his wife Bibi joined MK in exile (left).

Present and his comrade Kwena Mothogoane put up posters in Kimberley before the author and his wife Bibi joined MK in exile (left).

This was one of those moments when any decision made could easily have been the wrong one. If we chose to leave, we would need time to pack our things. We would then have to find a way to exit the hotel without being noticed. And, of course, they would probably have taken into account that we would try to run.

We agreed then that meeting in the hotel lobby would be safer than on the streets of Gaborone. I would go down alone and leave Bibi in the room. So it was with extreme reservation that I headed downstairs.

I had no idea what the person looked like, but as I crossed the floor, I scanned the place for any white person who seemed suspicious. At reception, I told the receptionist that I was expecting someone.

She pointed me to a man.

I could not believe my eyes.

Not only was our visitor not a white security policeman, but rather a black man — and he was dressed as a priest. And his first words to me were that he had been sent by Dr Allan Boesak.

I was so relieved that I immediately called Bibi from reception. That is how we met Walter Paul Khotso Makhulu, Bishop of Botswana, Archbishop of Central Africa (Malawi, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Botswana) and president of the All Africa Conference of Churches.

Peter Present

Peter Present

We would later learn that he assisted many other people like us who found themselves in dire straits.

Unbeknown to us, my father had made contact with Boesak and told him about our financial troubles. Boesak had, in turn, contacted Archbishop Makhulu, who provided us with the money for the balance of our hotel stay and return to Cape Town. He also took us to his home, invited us to spend a few days with him, and introduced us to his family and some of his friends.

One of the families he introduced us to was that of Dorothy Froese. Dorothy was a single mother of three children: boys John and Meraffe, and a little girl by the name of Tebogo. We visited them a few times, and in that time I quickly became fond of Tebogo, who must have been about two or three years old at the time.

I have very special memories of reading to her from her storybook on our evening visits. In this way, Bibi and I had another perfect alibi to prove that we visited people and places in Botswana that weren’t linked to the ANC.

At the time, however, even though he helped us from the moment we met him, I was still reluctant to put all my trust in Makhulu. It was nothing personal; this was just how I was programmed to react whenever I met a stranger.

I think we often underestimate the reality of how real and dangerous the issue of infiltration was at the time. At one point, he showed us some photos. In one of the pictures, he was standing next to Boesak. This, for me, was the physical proof of his connection to Boesak and one that finally allayed my fears.

We couldn’t be more grateful for all the help we received from both struggle stalwarts. Had we not received financial support, we would have had to make contact with the ANC in Botswana and enter the country illegally. As a result, we would then not have been allowed to go home, and our lives would probably have been very different. At the time, we never informed him that we were MK soldiers returning from training and on our way home to contribute to the liberation of our country.

He, in turn, never asked us why we were in Botswana. Somehow, he understood.

On 12 June 1986, four days after our arrival in Botswana and the day before our planned departure, a national State of Emergency was declared in South Africa. All political activity, including funerals, was severely restricted and policed. As we watched the news from our hotel room in Gaborone, Bibi and I knew that this would impact our ability to enter the country safely and travel to Cape Town.

Quiet Activists is published by Quickfox Publishing.