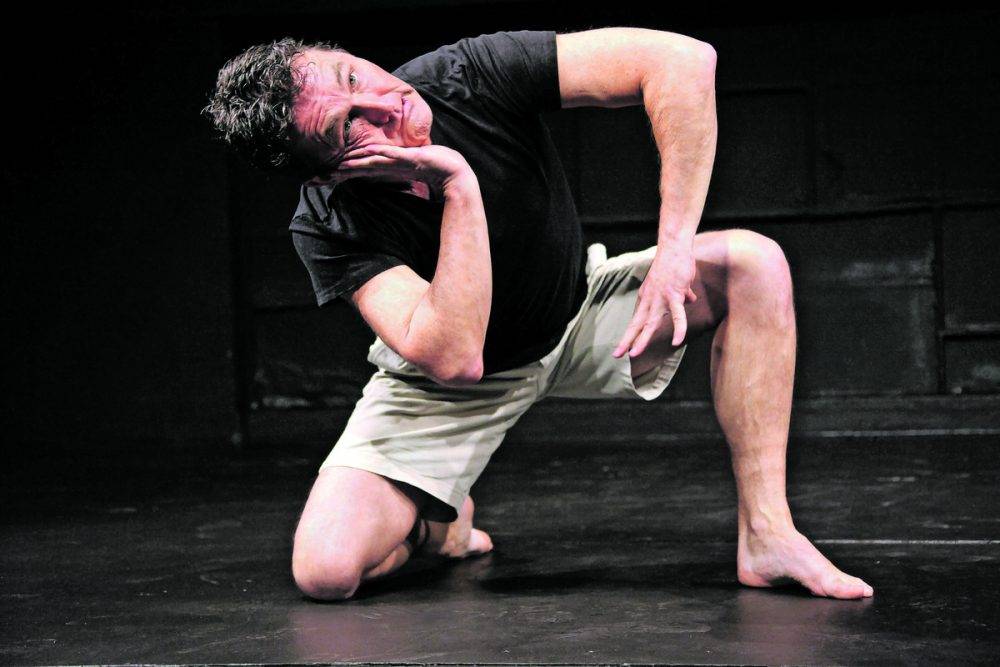

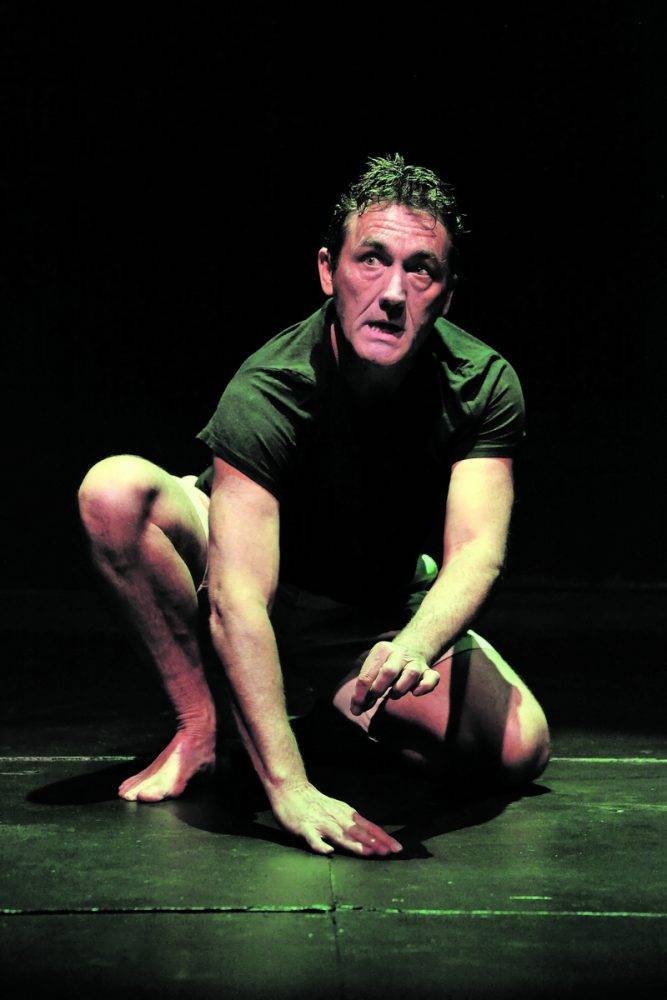

Don’t let it bug you: Andrew Buckland is back with The Ugly Noo Noo, which was first brought to stage in 1988. Photos: Ruphin Coudyzer

Actor Andrew Buckland is among our very best. Not only a major force in South African theatre but a powerhouse of human empathy, possessed of an ability to make you experience emotion with your entire body.

Buckland creates visceral theatre, makes you feel things in your gut, forces you to see things that aren’t really there by producing physical responses to imagined impulses.

In many ways the show that kickstarted it all, and which made the wider world aware of his theatrical superpower, was The Ugly Noo Noo.

Devised in 1988 and sparked by witnessing his wife Janet (the show’s director) react to a Parktown prawn, the play began as a late-night event at The Market Theatre and consequently evolved into something about as legendary and awe-inducing as the allegedly vicious little creature (actually the Africa horned locust) itself.

The show has been revived — following a run at The Baxter in Cape Town, it is playing at The Market. It is actually the first two parts of a trilogy that was ultimately truncated.

In it, for an hour or so, Buckland transports you to a parallel universe. No props, no set, no elaborate costumes, not even a mask. Just a man with an enormous heart, breathtaking ingenuity and what can only be described as an extravagant imagination.

Seeing Buckland perform and play in an empty space under the theatre lights as he revives this classic, cult-like show, is a reminder of what the human creative spirit makes possible.

Now 70, he remains as nimble and vivacious as the world’s most bright-eyed, agile teenager, albeit endeavouring with every cell in his body to not only entertain but also say something important and impactful.

Buckland, who says he was motivated in the early days of his career to use his craft to make a difference in the world, created The Ugly Noo Noo at the height of apartheid, when the political stakes were high and when he was otherwise actively engaged in protest plays and activist performances, whether against the government or to end military conscription.

His instinct was to use this physical performance about the irrational fear of a scary-looking insect as a way of commenting more expansively on the political use of fearmongering to drive violent agendas. What is perhaps impossible to anticipate is the kind of flair and elegance with which Buckland enacts a story that incorporates both elevated barbarism and creeping chaos — nevermind the level of sophistication he is capable of mustering to bring the story’s various personalities (human and otherwise) to life.

Scenes from The Ugly Noo Noo

Scenes from The Ugly Noo Noo

His characterisations not only animate a veritable menagerie of diverse creatures, but each of these seems to come with a full-scale backstory, whether it’s the psychotic tendencies of a chicken with a penchant for torturing his victims or an entire army of presumably brainwashed Parktown prawns caught in the grip of a kind of group-think impulse and taken in by the kind of slogan-chanting simple-mindedness that you might today associate with a Trump rally.

Part of Buckland’s genius as a performer is the mechanism of physical transition between characters. One instant he’s an irrationally hysterical human, horror-struck at the presence of a tiny insect in his kitchen, the next moment, he is the Parktown prawn, a kind of noble, sophisticated and politically progressive creature trying his utmost to make appeals on behalf of civilised beings everywhere.

The trick of the transition might manifest in a subtle realignment of the spine or the repositioning of a foot, or an alteration of vocal quality, but the effect is to convincingly become a succession of varying characters, each in the blink of an eye.

The breathtaking scope of his performance aside, what’s also astonishing is Buckland’s nimbleness as a performer. In a recent interview, he said, with age, he’s learnt to be more economical with his body, sparing himself the kind of exhaustion he would have experienced when he was half the age he is now. And yet there is barely a sign of any mellowing or of any wavering or tightening up. Buckland is as vital and as on form as he has always been.

Also still on full display is the zaniness, Buckland’s unhinged playfulness, that ability to completely and wholeheartedly let go, to give himself over entirely to the performance while maintaining expert control of his craft.

The effect is to sweep the audience up in the joyful, whacky and oftentimes wayward comedy of the performance while cracking open our hearts so that we’re touched by the pathos.

The show is weirdly and remarkably subversive, plays against our natural instincts as humans, and in so doing tries to remind us what it really means to be human, to feel for and empathise with even the most loathed and misunderstood creatures that dwell in the deepest reaches of our nightmare consciousness.

It is part of Buckland’s genius that he was — 35 years ago — able to imagine and realise a topsy-turvy universe to turn our perspective of reality on its head.

He does so not only by making us laugh but also with madcap writing that is as offbeat and cleverly quirky as it is prescient. You recognise parts of yourself in the characters he’s concocted, and you recognise the battle that’s raging between logic and absurdity, both on the stage and in the wider world that the show tangentially references.

While this play certainly speaks to the softer side of human nature, it is fundamentally a physical show, a demonstration of the human body’s strengths and weaknesses and a showcase of the body as something beyond the tight, almost authoritarian, control of the intellect.

It’s evident in Buckland’s full-body physical humour, in his slightly ribald jokes, his oblique references to sexuality and overt references to defecation and, of course, in the brutality with which he occasionally mimes horrific violence.

What he does through it all, though, is make an appeal to our humanity, to that part of who we are that makes us what we’re meant to be: caring, empathetic, sentient beings. And that, as much as for the pure genius of the performance, is why this show is not to be missed.

The Ugly Noo Noo runs at The Market Theatre in Johannesburg until 1 September.