South Africa has told world governments that the global war on drugs has failed and that it is considering plans to decriminalise personal drug use, while focusing its police resources on dealers and illicit syndicates.

Speaking on the sidelines of last week’s United Nations general assembly at the Global Commission on Drug Policy, Deputy Social Development Minister Hendrietta Bogopane-Zulu called for a review of treatment protocols for drug-dependent people, and a move to a “human-rights based” approach.

“We need to reduce the punitive, war-based language on the issue of drugs. This has not led to any of us being successful in the fight against drugs. We need to begin to focus on the social welfare services, so we can focus on putting the drug user at the centre and ensuring they have access to the critical medicines that they need,” Bogopane-Zule told social and welfare ministers from around the world.

This strategy forms the basis of South Africa’s drug master plan, published in June this year, which espouses a doctrine of “harm reduction” for drug users.

According to the policy framework, current legislation seriously affects the success of needle syringe programmes for people who inject drugs such as heroin.

“Criminalising drug use (which can include possession of injecting equipment) causes tension between people who inject drugs, police, and needle-syringe-programme service providers. This raises the importance of a unified philosophy across the system, which will ensure that stakeholders are not working against each other,” the document reads in part.

Bogopane-Zulu also acknowledged South Africa’s criminal justice system did not have the capacity to deal with the number of people arrested for having “small drug quantities for personal use, [which has] overburdened the system and has made access to services a real challenge.”

‘Soft targets’

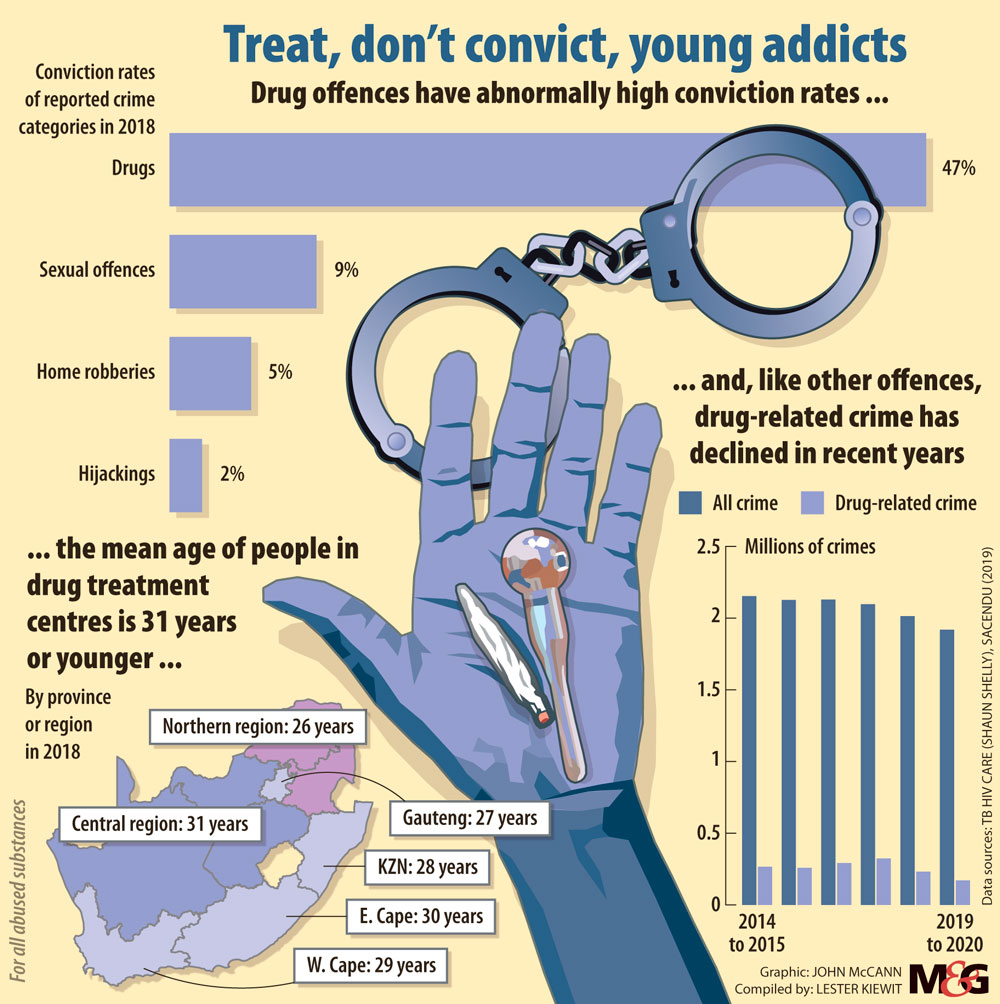

Police crime statistics show drug-related convictions to be disproportionately higher than other violations.

A total of 323 369 drug-related offences were recorded in South Africa between 2017 and 2018. Of these, 47% or 151 061 led to convictions.

In contrast, convictions for hijacking stood at 2%, home robberies at 5%, and sexual offences at 9%.

Head of drug police at nongovernmental organisation TB HIV Care, Shaun Shelly, said this was not an indication of good police work, but that law enforcement was using drug crimes to bump up crime statistics.

“There are a lot of people arrested without being charged. And the majority of the crimes being prosecuted are usually for very small amounts of drugs.

“A lot of those convictions are people paying an admission of guilt fine so that they don’t have to spend a weekend in jail,” Shelly said.

He added that these convictions for minor drug offences remain permanently on people’s criminal record, and could adversely affect them when trying to find future employment.

How many users in SA?

According to the World Drug Report, between 0.75% and 1.35% of South Africans use drugs.

Shelly acknowledges that an accurate number would be almost impossible to determine because of the illicit nature of the drug economy.

The closest South Africa currently comes to determining how many people use drugs is the 2019 South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use report. It details how many people have sought treatment for drug and substance dependence.

According to the report, alcohol is the most widely used substance in South Africa. Cannabis is the primary illicit drug for many people seeking treatment, accounting for between 33% and 50% of cases, depending on the province.

The report said cocaine treatment had seen a considerable decrease in recent years. It is also usually the second substance of use. There has been a rise in the number of people reporting for heroin treatment. In Gauteng, 27% of people seeking treatment were doing so for substances related to opiate dependence.

This statistic is echoed by Bogopane-Zulu, who said that intravenous drug users were “becoming a challenge”, as the risks of blood-borne diseases such as HIV and hepatitis increases.

Meanwhile, in the Western Cap, methamphetamine or tik dependence accounted for 28% of cases of people seeking treatment.

Changes to the law

For South Africa to change legislation and decriminalise personal drug use, it would require input from 18 government departments and entities, according to Shelly.

He has suggested the formation of a central drug authority that sits independently from any government department to oversee and implement legislative changes.

“Police should not be at the forefront of managing the drug issue. They should be managing transnational crime and crime syndicates. The issue of drugs should fall under social development, primarily. Departments that oversee jobs and businesses should be the next level of involvement, and then the health department.”

Shelly said many people resolve their drug use without any external intervention. He said factors such as unemployment play a role in people continuing with their drug use.

“We know that a lot of people, in the right circumstances, will automatically resolve their drug disorder. But in the South African context, people won’t resolve it because they have these real-life issues where the most meaningful thing comes out of their drug use. It’s a form of economic opportunity for some.”

This stance is echoed by Bogopane-Zulu who said that law enforcement agencies should separate the addiction of the user and the criminal aspect. “We must recognise not only the human rights of the drug users, but we [must] begin to criminalise the perpetrator and smuggler, and not necessarily the user.”