Shield: A Tanzanian woman and her child use a mosquito net as a preventative measure against malaria.

A malaria vaccine with 77% efficacy in children from birth to five years old — the age group with the highest fatality rate worldwide — is in the early stages of human trials at Oxford University.

The vaccine’s remarkable efficacy is being put down to it having leveraged off the Novavax Covid-19 vaccine technology.

An estimated two-thirds of malaria deaths are among children under the age of five, most of them in Africa.

The new malaria vaccine contains an antigen that mimics the infection and stimulates the body with the best immune response. The adjuvant (a substance that enhances the body’s immune response to an antigen) used was similar to that in the Novavax Covid vaccine, also developed at Oxford. Adjuvants have been a key adaptive component in many successful recent vaccines, including those for Ebola and H1N1 “swine flu”.

A phase three trial of the malaria vaccine has begun recruitment across five trial sites in four countries of differing malaria transmission rates and seasonality in Africa to study large-scale safety and efficacy.

The news has been greeted with enthusiasm in Africa, the world’s hardest-hit continent, where the previous four-dose malaria vaccine candidate reached just 56% efficacy over a two-year administration period, creating adherence problems and consumer resistance.

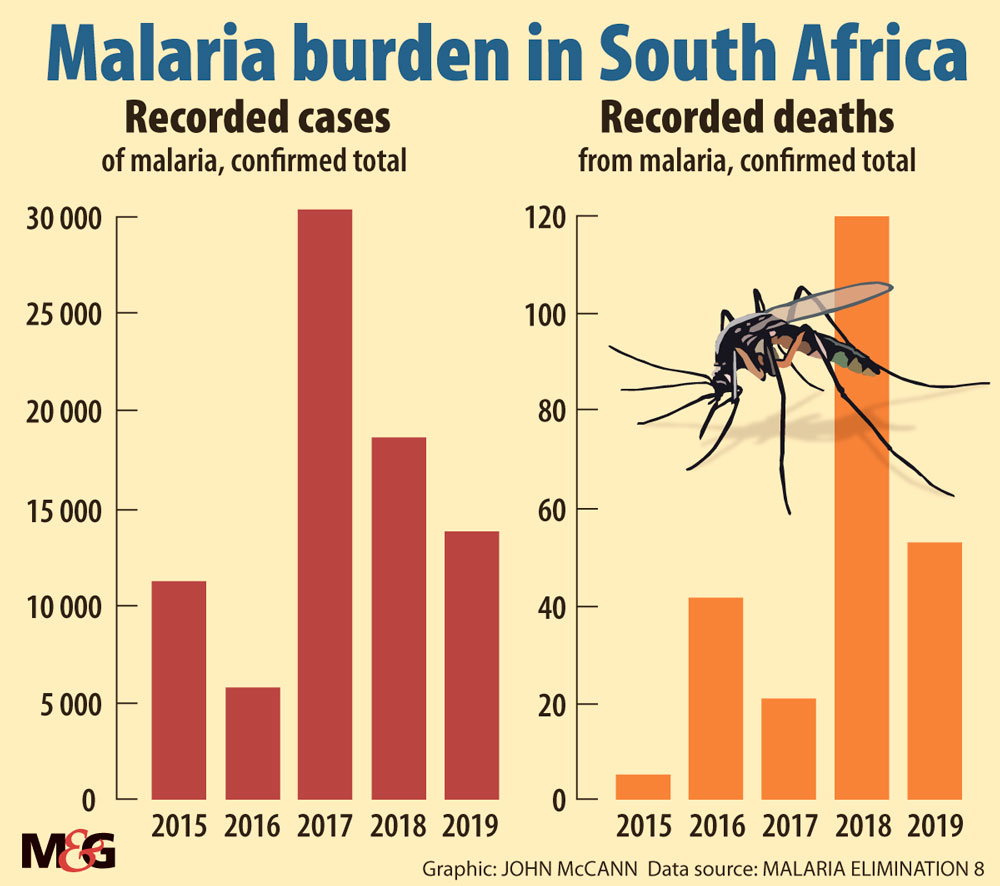

In Mozambique, 9.3-million people contracted malaria in 2020 versus just 8 000 annually in South Africa, according to last year’s statistics from the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD). The government has recently extended the malaria elimination target date from 2023 to 2025.

After an unusually high rainfall season in 2017 left 30 000 people infected, the government redoubled its malaria control efforts, and annual malaria deaths dropped from 331 in 2017 to just 38 last year.

The worst-affected countries are Nigeria at 61-million infections and the Democratic Republic of Congo at 28-million infections per year.

While the new vaccine will be a game-changer when it comes on stream in an estimated five years, indoor residual spraying, managing mosquito breeding sites, prophylactic medicine and early diagnosis and treatment are South Africa’s weapons of choice.

However, Covid-19 has complicated the malaria battle, with programmes forced to downscale their case-finding activities. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that a mere 10% disruption in access to antimalarial treatment caused by Covid could lead to 19 000 additional deaths this year.

Single dose jab passes test

Called the R21 Matrix-M, the new malaria vaccine is a single-dose regimen and has been tested in Malawi and Kenya, and, in the latest trial, on 450 babies in Burkina Faso, returning a 77% efficacy rate.

This is 2% above the minimum required by the WHO for vaccine distribution approval, after passing all other safety and efficacy tests.

According to the University of Cape Town’s Professor Karen Barnes, co-chair of the malaria elimination committee, the introduction of mobile malaria testing and treatment units along South Africa’s borders, especially with Mozambique, was a most successful move.

“Covid-19 has limited travel. While people have been more reluctant to go to healthcare facilities for fear of catching Covid, a lot of cross-border travel is undocumented, which is where mobile units help.”

She emphasised malaria was best caught within 24 hours of symptoms and could be treated within three days, while a finger-prick test for malaria took just 15 minutes and was less invasive than a Covid-19 test.

Says Sherwin Charles, chief executive of Goodbye Malaria, the largest NGO of its kind in South Africa: “Adult mortality rates have dropped significantly thanks to advances in medication, but in hospitals, wherever there is a malaria outbreak you see mainly kids and very few adults. The children develop severe malaria with complications, the worst of which is cerebral malaria, where the parasite clogs the arteries feeding the brain.”

The WHO says the disease kills a child every two minutes globally.

Children’s development hit

Charles says the disease has severe secondary effects, including stunting and slowing or severely impairing cognitive growth and thus educational prospects, with long-term impact on a country’s economy.

[related_posts_sc article_id=”258596″]

The WHO estimates that malaria killed an estimated 409 000 people annually across the globe in 2018 and 2019 (95% in Africa), with the 2020 estimate due out this October.

“It’s ludicrous that these WHO figures come out so late as we can’t possibly be agile in our responses with such a lag time,” Charles complains.

Barnes said mosquitoes from malaria endemic areas sometimes travelled with people or in luggage, spreading to non-endemic areas.

“It happens once in a purple moon, maybe a dozen a year, and it’s just bad luck,” she said. Mosquitoes in non-endemic areas did not carry malaria, she said, while confirming that there had been a few recent cases in Gauteng. The only other means of transmitting malaria are blood transfusion and congenital transmission, “both incredibly rare”.

South Africa has not subscribed to the highly successful insecticide-treated bed net covers, which last up to two years. The WHO spent billions of dollars distributing such bed nets across the continent, but many mosquito strains developed resistance to the chemicals.

Here, we still use the highly effective but environmentally harmful pesticide DDT for indoor residual spraying, but very sparingly and only in mud-walled and -floored huts.

Charles estimated that at least half of South Africa’s malaria cases were imported. In addition, “too many South Africans going to the Mozambican coastline don’t bother to take prophylactics,” he added.

Citing China, where government control is strong and the population more compliant, Charles said it was close to eradicating malaria — via mass administration of prophylactic drugs in problem cities.

“We have the tools to stop malaria globally, even without the vaccine. If everybody on the planet took a tablet over a three-day period and repeated this a month later in case of reinfection, you’d have a malaria-free world — but that’s a pipe dream. Here, the response would be, ‘Why must I take a tablet? I’m not sick!’”

Like the TB vaccine researchers, their malaria counterparts believe the inequity in funding between the first and third world and the lesser impact of these diseases on higher-income countries is responsible for tardy vaccine development.

By contrast the Covid-19 vaccine was developed in just over a year.

Barnes said malaria elimination was defined as well-documented zero local transmission for three years in a row, while eradication meant ridding the entire world of a disease.

Charles said on a recent radio show several callers were truck drivers who travel between Mozambique and South Africa. “The truckers … said access to medicines and treatment was far better in Mozambique and rapid tests were more easily accessible, while in South Africa they battled to find a practitioner with a test,” he said.

Charles said because South Africa has less widespread immunity to malaria, locals tend to get it more severely, while an adult vaccine was most needed. (Adults in higher-prevalence areas, however, develop immunity from childhood.)

He echoed a warning earlier this year by Professor Lucille Blumberg, founding director of the division of public health surveillance and response, a unit of the NICD.

Blumberg said that with the heavier rains in the sub-Saharan region this summer, more malaria was likely, and with symptoms that were similar to Covid-19, there was a danger of misdiagnosis, with potentially dire consequences.

Charles said shared symptoms included fever, headaches, diarrhoea, nausea and body aches. “It’s crucial that healthcare workers ask people whether they’ve been to a malaria endemic area in the past 10 days,” he advised.