there are no flowers in the streets where children play and the area has experienced four cases of child suicide in recent months. Photo: David Harrison

The singer Dana Winner’s words echo off the mountains in the Hantam region of the Northern Cape. “Let the children have a world. Where there is no pain or sorrow. Where they all can live tomorrow. And they share a brighter day.” A thin layer of snow covers the mountains, while thick clouds throw a veil over the small town of Calvinia.

On 29 July this year, 13-year-old Gaylinne-Corné Joseph took her own life, using the belt of her nightgown. Hers was one of four cases of child suicide in the area in recent months.

“She was an angel child. She differed from the other kids. She never gave you any reason to scold her,” says her aunt, Geraldine Gous. During an interview with the Mail & Guardian, Gous responds; Gaylinne’s parents, unable to find the words, simply nod in agreement.

“Gaylinne enjoyed school. Each time she brought back home her school report she would comment ‘Ek is ’n poppie wat klaar maak’ [I’m a girl who finishes],” says her aunt.

Her mother, Jenine Joseph, works at Hantam Primary School, where Gaylinne was finishing her final year. She would have gone on to Hantam Secondary School next year. Her father, Johannis Gous, is a security guard. The three lived in a government-built RDP house, where they shared a bedroom.

A primary school netball court and a sports field are testament to the neglect in Calvinia. (Photo by David Harrison)

A primary school netball court and a sports field are testament to the neglect in Calvinia. (Photo by David Harrison)

Gous says Gaylinne was a quiet, introverted person. “She was very close to her grandmother; she would stay there the whole day and talk to her. She wasn’t someone who talked easily. She must have really known you before she would open up.”

When Gaylinne’s cousin died of suicide in May this year, the family didn’t recognise any behavioural changes.

Gaylinne’s cousin was also 13 years old. They grew up together and were very fond of each other. The cousin went to Calvinia Primary School, not far from where Gaylinne went to school. She too had a special relationship with her grandmother.

But then the cousin’s mother, who is a police officer, was transferred to Upington at the beginning of 2021. The cousin left her friends and the environment she knew behind, and began school in Upington. She wanted to go back to Calvinia and was told that when she finished this year’s schooling she could return. But before that could happen, she took her own life.

“After her cousin’s funeral, Gaylinne talked and asked a lot of questions. But we never thought it to be a warning sign,” Gous says.

Gaylinne asked her grandmother why her cousin took her own life and how one could kill oneself with a nightgown belt. She also compiled a video montage of pictures of her cousin, which she would watch continuously.

“We were not aware that she was busy living herself in her cousin’s suicide,” Gous says.

The mountainous landscape and flowers surrounding Calvinia, the busy streets and historical buildings, are the images one remembers of the town. But it is in the streets that many children mill around during school hours. There are no flowers where they walk, and the locals say they have not been any for some time, ever since the 2016 and 2018 droughts.

There is no signal because two major mobile telecommunications units are out of order. When the M&G visits the town, some areas don’t have electricity, because of cable theft the previous night, “so, you know, this is Calvinia — it will probably be fixed much later”, says a shop owner.

A high unemployment rate, alcohol and drug abuse, poverty and socioeconomic problems have been prevalent for some time in the town.

“Our children are in a place where they have never been before,” says Aubrey Piedt, a school psychiatrist. He previously served large parts of the Northern Cape, but is now limited by the Covid-19 restrictions to the area in and around Calvinia.

“What the pandemic did was to underline the challenges our children face,” he says.

Piedt points out that children have overcome the stigma of visiting the school psychiatrist. “Lately, it has happened more and more that children themselves come to [see me]. They cannot cope any more.”

He says that by the time he sees a child their emotional load has already become a crisis, adding that the children carried this burden long before the pandemic.

“It is such a distorted picture,” Piedt says. “I have so much compassion for our town. It is just that there is no work and so much hopelessness.

“I’m experienced and [have] worked with many different cases before, but it is as if I have reached a point where I myself feel burned out,” says Piedt, who recently had to accept, for the first time, that he could not determine the reason a child would die of suicide.

The wall of a sports field in Calvinia in the Northern Cape, where there have been several child suicides over recent months. (Photo by David Harrison)

The wall of a sports field in Calvinia in the Northern Cape, where there have been several child suicides over recent months. (Photo by David Harrison)

“If someone can just notice the hopelessness …” he pleads.

Manuel Pieterse is the principal of Hantam Primary School, which Gaylinne attended. Pieterse grew up in Calvinia West, a large township next to Calvinia. He is aware of the myriad physical and emotional burdens placed on the shoulders of the children at his school.

He points out that children in Calvinia had survived the drought, before the Covid-19 pandemic hit.

The closed rugby field in Calvinia. (Photo by David Harrison)

The closed rugby field in Calvinia. (Photo by David Harrison)

“The majority of our children from surrounding farms have not returned to school,” says Pieterse, adding that there were nearly 200 dropouts last year.

“Covid really hit smaller towns like Calvinia, where most people depend on char jobs two to three times a week. These jobs disappeared instantly when the hard lockdown was enforced,” Pieterse says.

“The impact of Covid-19 has a ripple effect on families and it comes down on children as young as grade one and two. And children don’t know how to open up and to talk about their feelings.”

Pieterse recalls attempted suicides and suicides in both the primary and secondary schools. He says that when one child dies of suicide, it might start a trend, so the school acted quickly after Gaylinne died of suicide.

Children suffer in silence

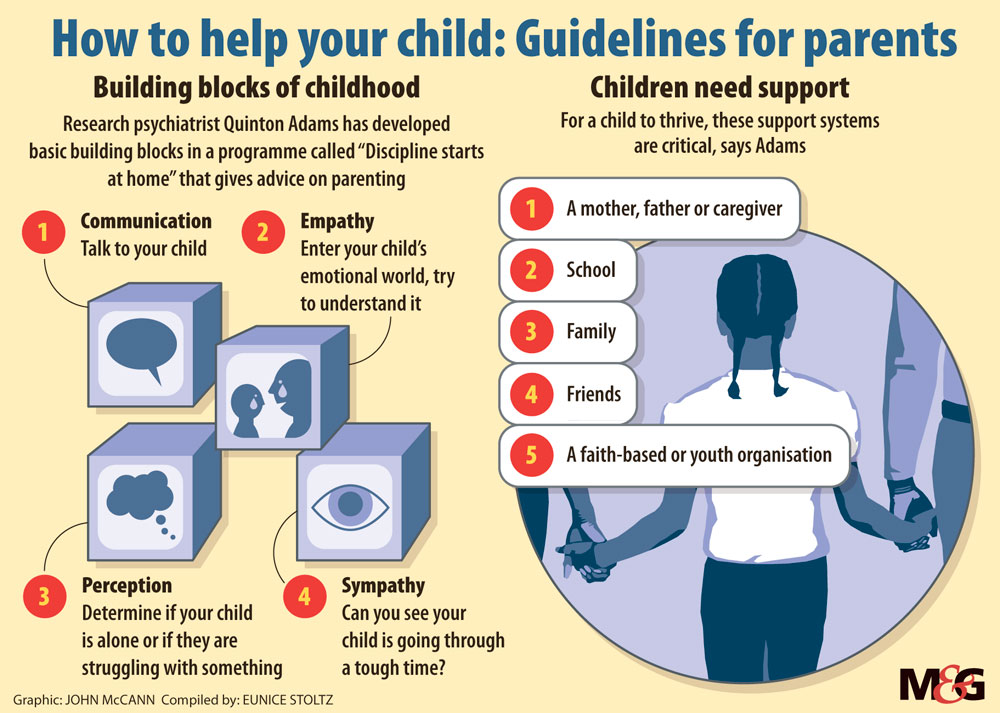

Quinton Adams is a research psychiatrist from Cape Town. He developed a programme called Discipline Starts at Home, which he introduced in Calvinia about nine years ago. Since first presenting the programme, he returns to the town every four years.

Harsh environment: The mountainous landscape and flowers surrounding Calvinia, the busy streets and historical buildings, are the images visitors remember of the town. (Phot: David Harrison)

Harsh environment: The mountainous landscape and flowers surrounding Calvinia, the busy streets and historical buildings, are the images visitors remember of the town. (Phot: David Harrison)

During his visit in August, Adams had informal interviews with more than 200 children younger than age 13. He shared some of the observations he made.

“Children struggle with grief and loss,” says Adams, adding that they then develop childhood trauma, and there are not adequate support systems to help them deal with that.

Children are being exposed to many deaths during Covid-19. “They don’t know what to make of it,” Adams says. “Children deal with anticipatory grief, asking who is next, because they hear the neighbour passed away, then their grandfather, and teacher, and next is a parent or friend.”

The support system many children depended on changed overnight when schools closed in 2020 because of the fear that Covid-19 might spread.

“We cannot expect children to be emotionally resilient when the school system and [home] system collapse. Where do they go? Children suffer in silence,” Adams says.

“There is a total disregard for children’s emotional experiences. Children feel isolated. Their parents are caught in financial difficulties and their main source of hope is cut off by not being able to go to school and talk to teachers.

“It is a total crisis. I have never before received so many inquiries about children [dying of] suicide in towns across the Western Cape, and especially in rural areas.”

Adams strongly believes schools do not know how to manage suicides and there are not enough organisations to support children, schools and parents in how to deal with emotional pain and daily problems.

Adams points out that memorial services can have an unintended effect on children after the death of a fellow learner. A memorial service celebrates the child and sometimes these events even worship a child, argues Adams. “A child [who] might feel brittle thinks if he also [dies of] suicide, he will receive the same attention and accolades.”

He says children must acquire the ability to ask for help. “Children don’t know how to handle psychological pain, yet they too experience it, just like adults.”

The South African Depression and Anxiety Group (Sadag) estimates that 23 suicides and 460 attempted suicides take place every day in South Africa. A startling figure by Sadag suggests 9% of all teen deaths are deaths from suicide. It is also the second most common cause of death in people aged between 15 to 29.

Hantam Primary School is far from giving up hope. The staff are working on solutions to teach children how to talk about their feelings. Adams describes it as a kind of “buddy system”.

The programme builds on the spirit and work of school psychiatrist Piedt, who is leading the initiative.

It aims to create a support system for children who need to talk about their circumstances or incidents that have negatively affected them. The programme guides children to speak to a trained teacher or peer to find out about how to access further support.

Back at Gaylinne’s home, her father says: “I miss her a lot. I must gather my thoughts at night before I go lay down. I know my child is not coming back.”

For Gaylinne’s family, there are still more questions than answers.

“We do not know what drove her to commit suicide. We don’t know what we could have done differently,” Gous says.

Outside their home, she points out to the mountain; a growing number of shacks occupy its hillside. “A few days ago you could see the snow at the top,” notes Gous, as soft rain carries the last words of Dana Winner’s song, “A child will find their own place in the sunlight. A child has hope, crystal light in their eyes.”

You can call the Childline South Africa 24-hour helpline at no cost on 116. Or you can visit the online counselling chat rooms, which are staffed from Monday to Friday, 11am to 1pm and 2pm to 6pm. Or go to the Child Welfare website to find the nearest child-support organisation in your province.