Vuyokazi Yvone Mathebula, whose younger sister Nonhle Gloria Aphane was murdered in June, comforts one of Aphane’s three children. (Ihsaan Haffejee)

Early on the morning of 25 June, Vuyokazi Yvonne Mathebula, 39, and her neighbour were reflecting on a funeral taking place a few streets away in Block V in Soshanguve, which lies about 30km north of Pretoria. The dead woman had been brutally killed by her son.

A few minutes later, around 9am, Mathebula received several calls from different numbers. She ignored them. But when her husband phoned she answered, only to be told that her younger sister, Nonhle Gloria Aphane, 30, had been strangled, allegedly by a close relative.

The news left Mathebula disoriented and feeling numb. When she got to her sister’s house in Ga-Rankuwa Zone 8, Aphane was lying face up and naked on a bed. She had blood in her mouth and nose and her stomach was distended, as if “she was nine months pregnant”.

It seems the mother of three children, aged three, five and 11, had been dead for days. “The room was stinking. I can’t even describe the smell,” says Mathebula. “It smelled horrible.”

Her body was discovered by the police, says Mathebula, after they had received a tip-off.

The tip-off came from a relative of the alleged suspect, who had “confessed” to the murder and requested that the relative call Aphane’s family to ask for forgiveness, says Mathebula. Instead, the relative phoned the local police, who liaised with the Ga-Rankuwa police station. The murder was confirmed and the suspect arrested. However, he was released from jail on 28 June.

Aphane’s mother, Eunice Ntombi Mtsishe, 72, says she cannot reconcile herself to the suspect’s release. “There’s no way that someone could murder a woman like this and be released from jail just like that. I have lost hope in the police because I really don’t see what it is that they’re doing,” says Mtsishe, who often pauses, weeping bitterly, during the interview.

According to Gauteng police spokesperson Lieutenant Colonel Mavela Masondo, the case “was not enrolled by the court pending further investigation”, including waiting for the postmortem results.

Mathebula says when she asked why the suspect had been released, the investigating officer told her that a statement had not been taken from the relative who heard the alleged confession. Asked about this and any progress in the case, Masondo said: “Unfortunately we cannot divulge more information as that might compromise the investigation.”

Unsafe at home

Aphane’s murder took place against a backdrop of rampant violence against women in South Africa. Most women are killed by their partners or ex-partners and many of them suffer months or years of domestic abuse before their deaths.

This is confirmed by data from Statistics South Africa, which released an in-depth report on the extent of gender-based violence, titled Crimes Against Women in South Africa, in 2020. It found that in the period 2018 to 2019, almost 50% of the assaults against women came at the hands of someone close to the victims – 22% were committed by a friend or an acquaintance, 15.2% by a spouse or intimate partner, and 12.6% by a relative or household member.

Stats SA’s key indicator report on the 2016 South Africa Demographic and Health Survey, which was conducted between May and November that year and included face-to-face interviews with adults from more than 11 000 households, stated that one in five women with partners – 21% – had experienced physical violence from a partner at some point, and 8% had experienced sexual violence in the previous 12 months.

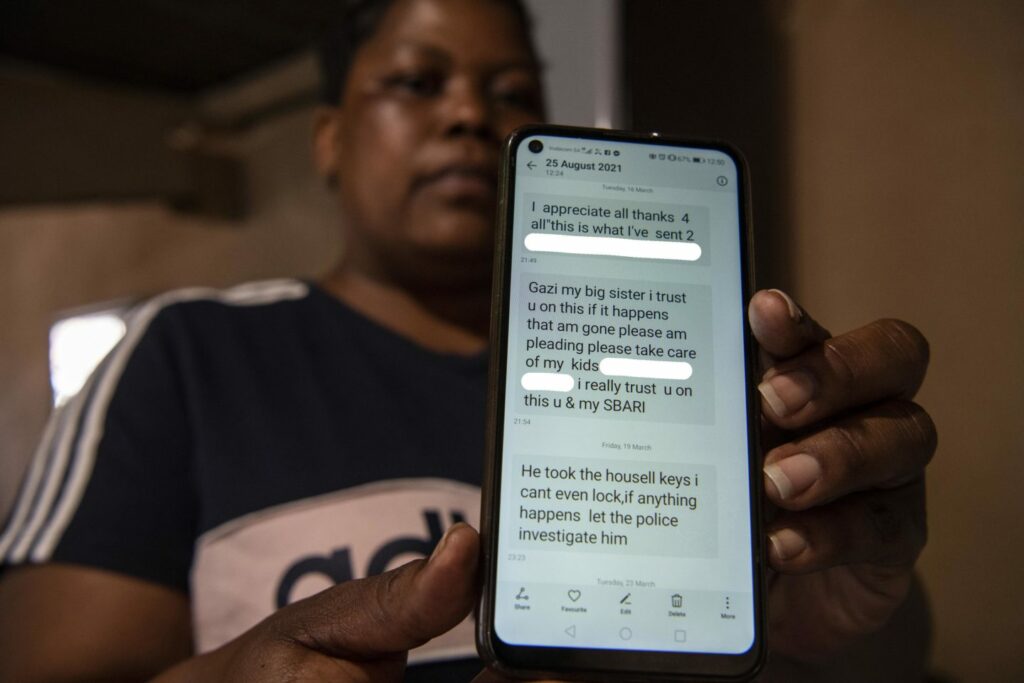

Vuyokazi Mathebula shows some of the text messages that were sent to her by her sister Nonhle Aphane. Some information has been erased from the photograph to protect the alleged suspect accused. (Ihsaan Haffejee)

Vuyokazi Mathebula shows some of the text messages that were sent to her by her sister Nonhle Aphane. Some information has been erased from the photograph to protect the alleged suspect accused. (Ihsaan Haffejee)

The survey suggested that those who were divorced or separated from their partners were the most likely to have experienced physical abuse (40%) or sexual violence (16%). Then followed those who were living with their partners (31% and 10%); widows (24% and 8%); women who had never married (18% and 5%); and married women (14% and 4%).

At Aphane’s funeral, close friends shed light on the extent of the violence that Aphane had endured. “I hate men,” one of her friends said. “I had to witness my best friend Nonhle being abused.”

The friend, who asked to remain anonymous, had known Aphane since 2007. She says she first noticed Aphane being abused in 2011. Having gone to a party together one night, Aphane confided in her the next day that she had been assaulted when she got home.

Routinely beaten and hospitalised

The abuse didn’t stop. Aphane would be beaten up “to the point that she’d be hospitalised”, says the friend. “When I went to check up on her, I could not even recognise her face the way she was injured.”

Last year, the friend says, things became worse and Aphane would frequently be in and out of hospital because of her injuries. The unceasing violence led Aphane to smoke and drink excessively. “She’d finish at least 20 cigarettes in an hour,” explains the friend. “That’s how stressed she was. She was drinking alcohol every day. She couldn’t sleep without alcohol.”

Dora Huma, 30, Aphane’s friend since the age of seven, says the assaults began even earlier, leading to a miscarriage before Aphane’s first child was born.

Rozanne Ashworth, a trauma counsellor, says women stay in abusive relationships for many reasons, including “fear of the abuser and what he might do if they leave, fear of being alone, fear of losing a roof over their heads, particularly if there are children involved, fear of being judged”.

“The fact that they love the abuser … might seem like a completely foreign concept to us, but there is often deep love for and emotional attachment to the abuser,” adds Ashworth. She says abused women might also be held back by a feeling of worthlessness, which is “often instilled by the abuser and concurrent with an already low self-esteem. The abuser repeatedly tells the abused that they are useless, no one else would want them, they are ugly, stupid, pathetic, etc.

“A woman will do what she needs to survive for her life, in her relationship with her abuser, for her kids’ sake, for acceptance in society. What we see as weakness by staying in an abusive relationship is often strength that we could not even begin to understand or comprehend.”

Cost to society

What has been less well documented about gender-based violence against women is its economic cost to society. A 2014 report released by KPMG, titled Too Costly to Ignore the Economic Impact of Gender-based Violence in South Africa, attempted to address this.

The report pointed out that the whole of society pays for the costs attached to violence against women, including healthcare, justice, lost earnings, lost revenue and lost taxes. Then there are second-generation costs, which include increased juvenile crime committed by children witnessing and living with violence, as well as crimes they commit later in life as adults.

For the period 2012 to 2013, the report estimated that the economic impact of gender-based violence was between R28.4 billion and R42.4 billion, representing 0.9% and 1.3% of gross domestic product respectively.

Nuclear and extended families and close friends also suffer psychologically when gender-based violence takes place. Like Huma says, a part of her is dead, too, and she cannot stop thinking of the times she shared with her friend. “We’d come to Nonhle’s home together, and now that she’s gone, the kids when they see me, they also think their mother will show up.”

Huma works as a security guard at the power station close to the graveyard where Aphane is buried. “Every day I go to her grave. I talk to her every day,” says Huma. “She was more than a friend to me, she was a sister. I miss walking together to the mall. I miss sitting together to look after her kids.”

Mathebula says the way in which her sister was murdered has left her with deep scars. She had to be admitted for trauma treatment at the Centurion-based psychiatric Vista Clinic, where she stayed for 21 days. Currently, she’s on special leave until early next year. “If I stop taking the medication that I received from the hospital I have visions of how my sister died,” says Mathebula.

This article was first published on New Frame